Here’s the Reason for Night and Day, According to Japanese Mythology

Throughout history, ancient peoples and religions have often represented the sun and moon as deities. Shinto (literally, “way of the gods”), a Japanese ethnic religion with records dating back to the 8th century, sought to explain the natural phenomena of the universe through kami, which can be defined as spirits, essences, or gods. Kami does not represent a single god, but rather several divine beings that can manifest in various forms. According the Nihon shoki, one of the earliest written recordings of Japanese history, the origins of day and night can be traced back to the sibling rivalry of three kami.

The three kami

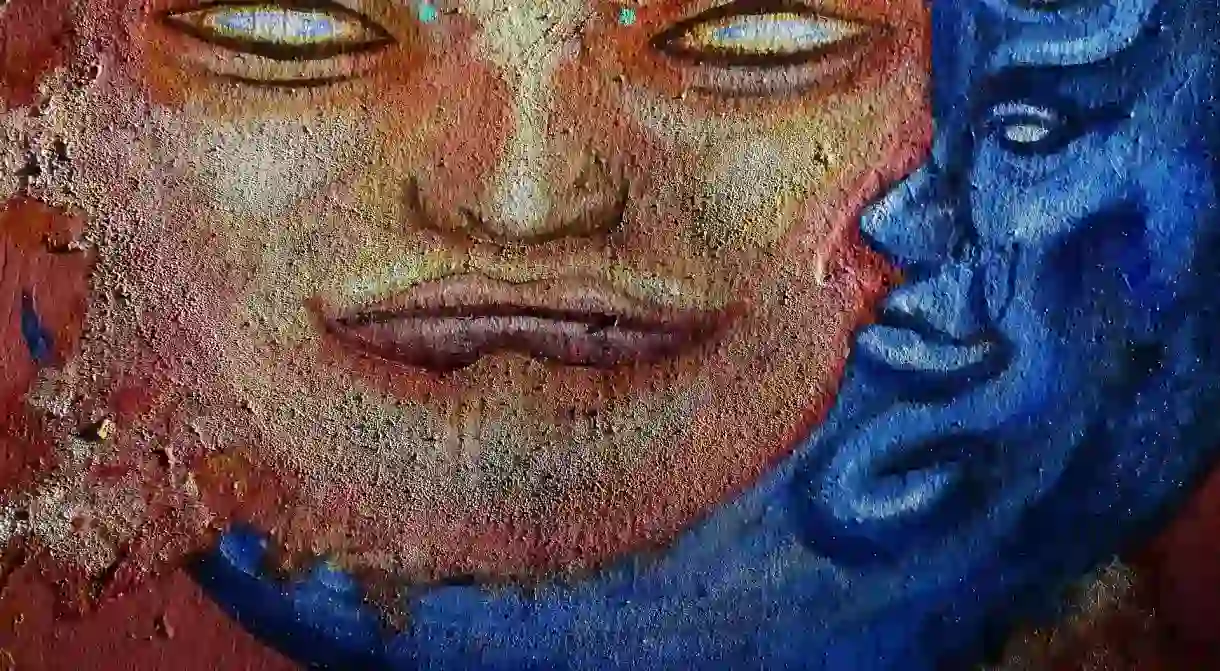

A long, long time ago, the god Izanagi-no-Mikoto and goddess Izanami-no-Mikoto got busy and produced three children: Amaterasu, goddess of the sun and ruler of heaven, Tsukiyomi, god of the moon and ruler of the night, and Susanoo, god of storms and ruler of the seas. Amaterasu, whose name translates to “shining in heaven,” would go on to be a major deity of the Shinto religion. Tsukiyomi, her brother (and also her husband), initially ruled the sky and heavens together, while her other brother Susanoo was cast out of heaven due to bad behavior and forced to spend the rest of his days in what is now known as Shimane prefecture.

The murder of Uke-Mochi and the separation of day and night

Amaterasu ordered Tsukiyomi to go down to earth to visit Uke-Mochi, the food goddess. Uke-Mochi had a rather peculiar way of producing food: by vomiting and defecating it onto the Earth. Upon seeing this, Tsukiyomi became so disgusted and enraged that he murdered Uke-Mochi before returning to heaven. When Amaterasu learned of what he had done, she declared him an evil god and vowed never to see him again, thus separating night and day for all of eternity.