The Art of Sakti Burman | A Private Universe

One of the pioneering post-Independence artists of India, Sakti Burman creates private, interior worlds within his art, borrowing from mythology, experience, history. Rosa Maria Falvo takes a close and thoughtful look at this complex artist’s life and work.

‘There is for every man some one scene,

some one adventure,

some one picture that is the image of his secret life,

for wisdom first speaks in images,

and that this one image,

if he would but brood over it his life long,

would lead his soul,

disentangled from unmeaning circumstance and the ebb and flow of the world,

into that far household where the undying gods await all whose souls have become simple as flame,

whose bodies have become quiet as an agate lamp.’

William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), from The Philosophy of Shelley’s Poetry (1900)

Sakti Burman’s artwork invites us to identify this numinous presence, and to celebrate and cultivate it. He pays special attention to it and even pays tribute to it, recognising the importance of a ‘secret’ inner world. Indeed, his work aims to enliven this presence in daily life – ‘making the private world public’ – as another poet, Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997), said of poetry itself. Burman’s lifelong dedication to painting is like the continuous musings of poets, intent on unveiling, little by little, from one thought and anecdote to another, the Sanskrit notion of maya (indescribable divinity) and its ultimate influence behind every creative endeavour. His own ‘lonely poet’ takes on many guises. And as the artist explains, ‘my hopeful figures roll out onto the stage, one after the other’, despite the cultural miserablism that seems to pervade our media-based consciousness, where the power of the negative story, with little redemption or escape, is encouraged to wallow in its own bleakness. Burman still dares to surrender himself to his imaginings of an idyllic world.

This artist’s outlook, his efforts as a migrant, successfully spanning two very different cultures and geographical realities, is testimony to his irrepressible creative verve and the very spirit of his Bengal, where the role of tradition, art, and ritual in contemporary life are not to be underestimated. Instead of portraying the torturous struggles of the human condition, Burman chooses to live in a private, ‘half-full’ kingdom, which he explores daily. And he has even developed the kind of painting that audiences both domestic and international find recognisable, yet personal, and something to which they can surprisingly relate. Burman’s imagination, free as a naked child, is portrayed notionally to the outside world but, more importantly, to himself. One could ask: are these just ‘tales’ – brimming with characters in spellbound gazes, luxuriant settings, and explosive delights – he likes to tell and retell himself? Perhaps his greatest export, from Asia to Europe and back, is the diversity of his own ‘fiction’, with the myriad of colourful alternatives between its contrasts and all his heroes and heroines. Here is an artist who happily looks on the past with the eyes of the present, which for him is a recurrent continuum, like the greatest of all narratives – one’s own life story.

Burman’s work, in true Romantic tradition, aspires to the infinite expressed by all means available. Nature, human and otherwise, is like a sacred temple the ‘artist-poet’ approaches through a forest of symbols, chanting Baudelaire’s mantra as he enters: ‘Even in the centuries which appear to us to be the most monstrous and foolish, the immortal appetite for beauty has always found satisfaction’. And closer to his original home, the sentiments of Rabindranath Tagore: ‘I have become my own version of an optimist. If I can’t make it through one door, I’ll go through another door – or I’ll make a door. Something terrific will come no matter how dark the present’. Tagore was quick to determine that ‘in Art, man reveals himself and not his objects’, so the artist’s challenge is the difficulty of being in the world but not of the world; essentially constructing a private universe. Even Burman’s juxtapositions of good and evil have an optimistic outlook, like the serenity of his Artist Painting Adam and Eve (2006) and his quiet recognition of the fact that humans simultaneously make life and take life, illustrated in his Love and Violence (2007) painting.

Western academic traditions have often harboured an insidious tendency to underestimate what comes from afar, superficially judging it as decorative, naïve, simplistic, or illustrative, presumably to guard against alien infiltrations of aesthetic phenomena into established and hard-won visual and cultural frameworks. Of course, the dynamics of influence in today’s art world have certainly shifted, even if individual attitudes may struggle to follow suit. Thankfully, Sakti Burman’s oeuvre provides a living bridge, across very different historical periods and between two otherwise estranged worlds. Born in 1935 in Kolkata, he grew up in what is now Bangladesh, and studied at Kolkata’s Government College of Art and Craft (GCAC), founded in 1864, the oldest art institution in India. Moving to Europe on a French government scholarship, he graduated from the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-arts in Paris in 1956. Today he is considered one of the pioneering post-Independence artists of India, where he maintains strong ties and exhibits regularly, often alongside his wife, French painter Maïté Delteil.

A revolutionary art movement – the Bombay Progressives – asserted itself in India between the nation’s Independence in 1947 and its unprecedented economic boom in the 1990s, propelling its modern and contemporary art into a globalised era, supported by a soaring international market and an explosion of art mediums. Artists responded to the challenge of expressing their unique character while engaging in European modernism’s premises of experimentation and shared human values. Painters began producing in absolute freedom, blending whatever influences they carried – from Expressionism through to Tantric spiritualism; from Rajasthani miniatures to loudly politicised responses to the enormous social changes – while writers critiqued the many problems of a newborn reality, like the handling of Partition between India and Pakistan. As a young man, Burman no doubt also felt free in his Parisian environment to experiment across art forms and continents, unfettered by cultural or academic definitions. From marbleising in oil to weathered fresco techniques, he polished and perfected his countless, subtle details to amuse and amaze his audiences as much as himself. The acknowledged origin of his creative muses were the women weavers of Bengal, the music and stage sets, and the framed landscapes of European masters, all of which was set against his memories of the Bengal famine, India’s nationalist movement, the loss of his mother and family wealth with Partition, and the need to ‘refill’ his courage through his artwork. He admires Picasso’s life and legacy, quotes Irving Stone’s novel Lust for Life on Van Gogh and Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, loosely based on Gauguin’s life, and admits that even from a tender age all he wanted was to dedicate his life to art as they had done.

As I watched Burman work in his studio in Paris and listened for hours to some of his stories, I got the distinct feeling that each painting is a new kind of birth for him; the beginning of a desire, interest or energy, which even in his mature age he is in a hurry to create and advance, as if it did not entirely belong to him. Rather like a child who cannot wait to share something with you. Judging by his frequent need to ‘get back to work’, his art seems to be his therapy, enabling him to metabolise larger narratives. His reds and golds, like rising suns, and ashen or wistful cobalt blues, the kind you might notice just before and after a new moon, are like distant clouds travelling across the seas of his imagination. It’s as if the planet sings with him, the poet, of a calm and wholesome beauty, rich in promise about the coming day and the painting to be born. All the while his face glows with childlike impatience. Inhabited by disparate ‘players’ and tangential narratives, when viewed in the context of a whole painting his strangely familiar faces occupy a parallel world of possibilities. And his emotional landscape is central, as he becomes the invisible protagonist who insists on his retreat from the distractions of ordinary life.

With the death of his mother early in his life and a frequently absent father, the artist’s brothers and extended family became his regular caretakers. Later Burman’s own family members – Maïté Delteil, his wife and accomplished artist, their son Matthieu and daughter Maya, also an award-winning artist, and grandchildren Ganapathy, Èvariste, Estelle and Lila – are constantly portrayed in his work, taking on their own personas in an ongoing narrative that fuses myth and reality. There appears to be little adherence to distinct or definitive messages, and instead his imagery blends, overlaps, and intertwines, like feelings do as a child relishes a new bedtime story. Burman’s early development in Paris was also influenced by French artist Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), one of the Post-Impressionists of Les Nabis (‘prophets’), who preferred to paint from memory, often creating dreamlike, intimate domestic scenes featuring his wife. Like him Burman relies on voluptuous colour, poetic allusions and the occasional visual wit.

Borrowing frequently from Hindu and European mythology, Sakti Burman manipulates as much as the visual space allows, creating an interiorised atmosphere. Indeed, his early work of the 1970s is surrealist in its suggestions, but does not follow any particular influence. Over the years he has developed his own aesthetic, which often conflates his mediums, such as his characteristic pastels with his oil paintings or his watercolours with his sculptures. Drawing on his cultural affiliations with Bengal and a convivial appreciation for people, Burman orchestrates a charming interplay between imagination and experience. The artist’s visual language fuses his storytellers with the metaphysical modalities of history. Its seduction lies in its originality of perspective. However, symbolic or figurative, he is utterly personal. And his figures appear as independent entities. Naturally, one’s aesthetic experience of any art is entirely subjective and fundamentally intangible in any measured form. But Burman’s work is deliberately inscrutable, and seemingly self-motivating. His culturally kaleidoscopic approach – quite literally inspired by its ancient Greek etymology (‘observing beautiful forms’) – is afforded by the fact that he migrated to France as a young man and was adopted through study and marriage into a foreign culture. So his work tumbles the viewer into a series of multiple and hybrid experiences. Like a palimpsest, Burman’s choice of content, often reliant on daydreams or memories, is erased, re-written, and superimposed on ancient motifs and the promise of fresh ideas. This kind of augmented reality, melding and layering people and places, makes for his unique style of representation. And it is not by chance that his artistic curiosity lured him through the wonders of Classicism, the Medieval, the Renaissance, and Modernism, with frequent visits to Italy early in his career.

Burman’s oiseleur figure, which began appearing in his early 1980s work, is reminiscent of Mozart’s loveable Papageno in The Magic Flute. With free associations to the celestial world, feminine energy, the heart, the soul, the lover, and the rogue, Burman’s voiceless Birdcatcher, essentially an avian Everyman, seems joyfully attentive of Mozart’s allegorical exclamation for the education of mankind – from chaotic superstition to rewarding enlightenment – making ‘the Earth a heavenly kingdom, and mortals like the gods’, as reiterated in both acts of this much loved opera. Of course, birds are coveted for their beautiful song and exquisite plumage, but being naturally cautious, skittish creatures, they are difficult to trap:

The bird-catcher, that’s me,

always cheerful, hip hooray!

As a bird-catcher I’m known

to young and old throughout the land.

I know how to set about luring

and how to be good at piping.

That’s why I can be merry and cheerful,

for all the birds are surely mine.

The bird-catcher, that’s me,

always cheerful, hip hooray!

As a bird-catcher I’m known

to young and old throughout the land.

I’d like a net for girls.

I’d catch them by the dozen for myself!

Then I’d lock them up with me,

and all the girls would be mine!

If all the girls were mine,

I’d barter plenty of sugar:

the one I like best,

I’d give her the sugar at once.

And if she kissed me tenderly then,

she would be my wife and I her husband.

She’d fall asleep at my side,

and I’d rock her like a child.

‘The Birdcatcher’s Song’, from Mozart’s The Magic Flute, K. 620, Act I

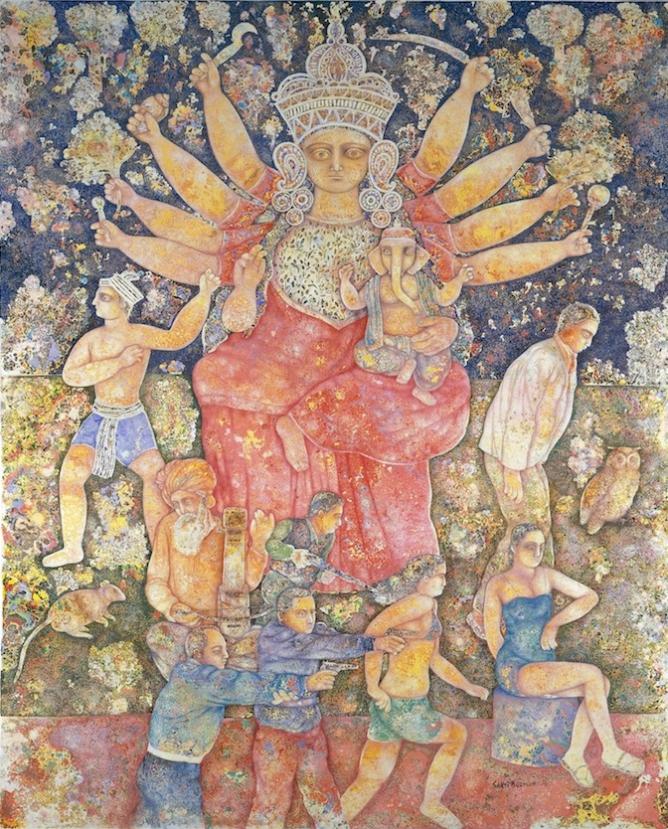

Another of Burman’s light-hearted and resourceful romantic heroes is his own harlequin, perhaps inspired by Cézanne’s celebrated version in Harlequin (1888–90). A stock character in medieval passion plays, Burman seems to use his discreet power, by virtue of his simple presence and contemplative poses, to weave some kind of ‘magic’ on his canvas alongside supporting characters like children and friendly serpent spirits in Harlequin with his Dreams (2012) and most recently with his own grandson Ganapathy in Harlequin (2014). At the same time and frequently in the same artworks, Krishna, Ganesha (elephant god), Hanuman (monkey god), Durga (warrior goddess), Shiva (Great One), Parvati (Mother), and even Gandhiji (Mahatma Gandhi) are featured among his cast of characters. Naturally, the deep well of this artist’s cultural legacy is always at hand. And as in the great Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, hisKrishna is also depicted as a boy playing a flute or a guiding prince, a god-child, prankster, perfect lover, philosopher, reformer, divine hero, and ultimately the Supreme Being. Easily recognised with his blue skin, bright orange dhoti and peacock feather crown, Burman’s painterly poetics may even be echoing the ancient verses themselves: ‘As a man, casting off robes that are worn out, putteth on others that are new, so the Embodied (soul), casting off bodies that are worn out, entereth other bodies that are new. Weapons cleave it not, fire consumeth it not; the waters do not drench it, nor doth the wind waste it. It is incapable of being cut, burnt, drenched, or dried up. It is unchangeable, all-pervading, stable, firm, and eternal…’ (Mahabharata, Book 6, Chapter 26).

Since antiquity, the sensorial being has been a cornerstone of the Indian art tradition. Artists have searched for forms and images to unlock the enigma of perception, and the suavity of its secular art offers profound and celebratory insights into a unified and humanistic experience. Burman offers a wealth of such suggestions and attempts to involve us in his own aesthetic ecstasy. This is his gesture of hope; the expression of a deep yearning that a few magic words and an artful hand might transport us from the sometimes crushing cruelties of the external world. Is this extravagant escapism? A vain desire to break free from the straitjacket of known physics, if only for an instant? A frivolous attempt to poke one’s nose into a spirit world waiting beyond? Of course, on some level all art is fantasy, a kind of transportation, attempting to lead us ‘somewhere else’ rather than ‘right here’. And Burman tries to fulfil a basic and merciful service, the way a parent might read to a child who longs for magical powers against the bullies at school. Indeed, he entertains our inner child, at least temporarily, offering some respite from what we may have lost or what we might regret or even the pressures of tomorrow.

Sakti Burman manages to weave together some interesting metaphors: the artist as a child, in the watercolour L’Enfant de la Haute Mer (1959) – riding the oceans beyond borders and jurisdictions – evoking that mare liberum of ultimate personal freedom. He takes up this idea again some twenty years later in his oil painting Enfant de l’au-delà (1982), alongside creatures of the underworld – that chthonic realm pertaining to deities and demons, evoking abundance and an afterlife; the artist as a bird, intrinsic to feminine energy and influence, is suggested inhiswatercolour Young Girl with Pigeon (1970), his Bird Girl etching of the same year, and echoed throughout his oil works such as Femme-Oiseau (1975), the masterly L’Oiseleur (1982), and his ‘Flying Lady’ (2010). And finally, the artist as a reflection of his audience, making frequent entrances under many guises across his own theatrical stage: with his initially conventional Self-Portrait (1959), his demurely anonymous ‘heads’ and ‘clowns’ in the 1960s, his metaphoric Man and Two Masks (1972), his multidimensional ‘mirrors’ throughout the 1970s, followed by his ubiquitous harlequins in the 1990s, a boldly enigmatic Self-Portrait (2012), and a scattering of Sādhus, dedicated to liberation, self-realization and self-knowledge. Luckily, his new millennium saw the birth of his first grandchild, Ganapathy – named after Ganesha, the god of beginnings – echoing the artist’s own renewed boyhood, and the removal of any existing obstacles to a fully-fledged command of his art. Burman’s Modern Jupiter (2009), discreetly holding the seat of power – a contemporary king in a bowler hat and jacket, supposedly presiding over all skies – is our incumbent divine witness to justice and good government. Burman’s playfulness even casts an artist-poet in bronze, as an objective (and objectified) Onlooker (2012), coming full circle in his recent oil work as a Divine Child (2014) – the custodian par excellence of the artist’s own Eternal Legend (2014). Sakti Burman seems to support the notion of anima mundi, which is happily in keeping with his East-West philosophical bridge building. And for me, following his personal journey, it is also reminiscent of another affirmation from another world again:

We Are Never Old

Spring still makes spring in the mind

When sixty years are told;

Love wakes anew this throbbing heart,

And we are never old;

Over the winter glaciers

I see the summer glow,

And through the wild-piled snowdrift

The warm rosebuds below.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), from The World-Soul (1904)

By Rosa Maria Falvo

Rosa Maria Falvo editor of SAKTI BURMAN: A Private Universe (2014), artist’s retrospective monograph published by Skira, Milan, Italy & Art Alive Gallery, New Delhi, India.