Meet the Woman Changing Perceptions of Female Sport in India

“Girls belong at home, not on the sports field. Girls should cook, look after the home and raise children – that’s their role in life”. This the world that Deepika Kumari grew up in. And the world she came to dominate.

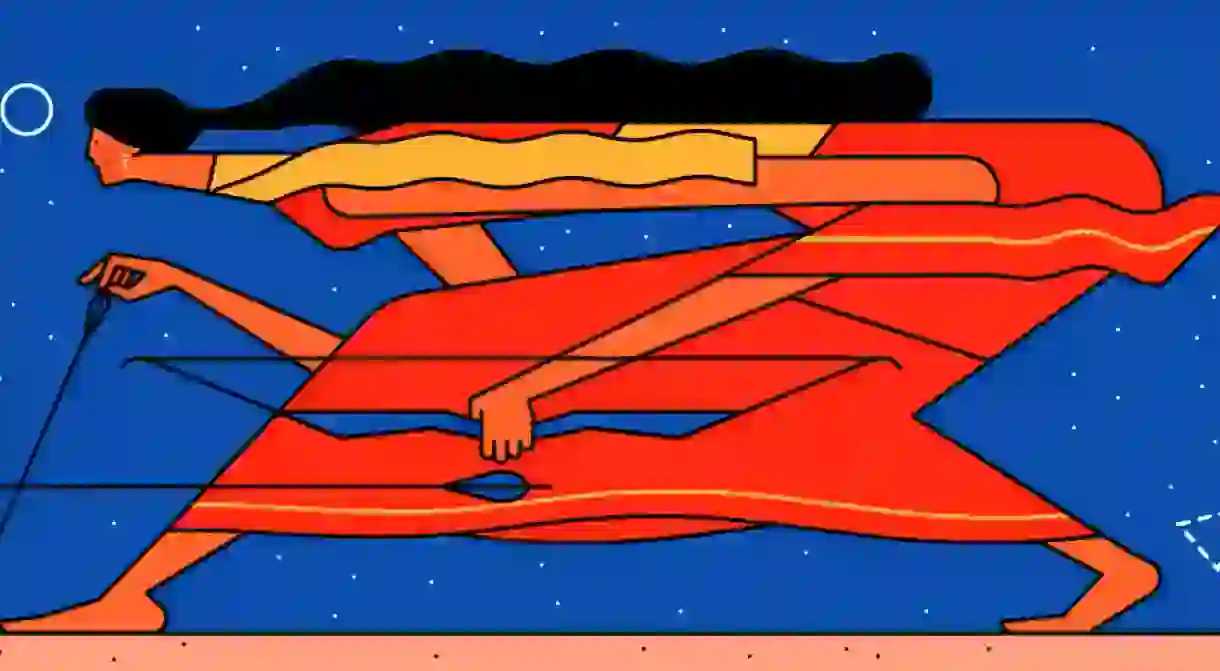

The above quotes are taken from the start of Ladies First, a new short film released on Netflix that documents the life of Kumari and her rise from abject poverty to elite athlete. Born on a roadside in rural India, she stumbled upon archery almost accidentally and quickly excelled at it, before suffering from the pressure and expectation put on her as a female athlete in a country where women simply don’t play sport.

Kumari tells us, “In our country even those who are well-educated believe that girls cannot play sports. I often feel like responding, but if I respond with my words they will forget. If I respond with my arrows, they can’t forget.”

https://youtu.be/L6iqoFg-hyg

The film’s protagonist was born in Ratu Chati village, 15 km away from Ranchi in the Jharkhand region in the east of India, and the country’s second poorest state. Her father was a rickshaw driver and her mother a nurse, with both giving up parts of their small income to help fund her training. Having discovered the sport as a child, she practiced using bows and arrows made from bamboo, with mangoes and stones as targets.

At the age of 12 she left home in an attempt to turn archery into a genuine career. Since then she has become a multiple Commonwealth champion, world record breaker and ranked number one in the world, and yet still has to fight against perceptions and prejudice.

As a girl and the eldest child, Kumari’s early life was spent washing clothes, helping with chores and being prevented from leaving the house. It is far from uncommon, there are only a handful of working women in Ratu, like so many other villages in India, just housewives.

Her mother, despite working in the village hospital would only be paid once every three or four months. Her house that her family shared with her uncle and aunt, was made from mud and leaked when it rained. The fact her mother had a job was the cause of fighting, with her uncle beating her mother as a result.

Key to her taking up archery was the fact it was free to play, with clothes and food provided. Initially her coach said she was too weak. Her response, “Give me three months, if I’m not good enough you can kick me out of the academy.” He agreed.

It wasn’t that she loved archery, far from it, she had never seen it before, even after starting she still didn’t know it was a sport. But if she left home for three months she believed she would be one less burden for her family and maybe the fighting would diminish.

The archery camp where she stayed had an extremely basic setup. Just three bedrooms with a bed and nothing else, no wardrobe, so drawers. There were no bathrooms, just a river nearby to bathe in. On one occasion, Kumari became ill, covered in boils and was rushed to hospital. The illness was a result of the sewage that filled the river she bathed in.

According to Kuntala Paul, the matron at the TATA Archery Academy, where Kumari was accepted as a 13-year-old, “She was a naive village girl, with no confidence. She didn’t know how to eat, sleep or dress properly. We taught her how to eat with a spoon and how to carry herself.”

Her success since has been extraordinary. It simply shouldn’t exist, there isn’t the infrastructure to support or nurture her skills and yet she has managed to craft it herself. Purnima Mahto, the Indian women’s archery coach, says, “Her talent is nothing short of a miracle. Within just one year of starting archery, she became the Cadet World Champion. Within three-and-a-half years she was world champion, unheard of in archery.”

At the London Olympics, however, the world was pulled out from under her feet. Going in as world number one, and with gold medal expectations weighing on her, she crashed out early in the tournament. On her return to India pressure mounted, her performances dipped and she lost her place on the team.

Starting again from the bottom, Rio 2016 became the new goal. Between London 2012 and Rio 2016, India held seven Olympic trails. Kumari broke the world record in each of the first three trials. At the World Cup in Shanghai in 2013, she equalled the world record. But weeks before Rio she suffered a shoulder injury.

Kumari’s coach believes she should have been selected for the Olympic team long before her injury occurred, and that the country’s sporting authorities, through their apathy and lack of planning, forced too much of a physical burden on her body. When she left for London, with tendinitis in her bicep, she went with an Indian team that sent no physical trainer, no nutritionist and no mental coach. While she flew economy class, the two government officials accompanying her flew business class.

Her defeat in the quarter-finals meant she came home empty handed. She talks about the fact that no one in her country respects her because she doesn’t have an Olympic medal to her name, despite the fact that no woman in India (a country of 1.3 billion people) has ever won an Olympic gold medal.

“In our country girls have big dreams, and big ambitions, but are held back by fear.” Kumari explains. And she’s right. Less that 1% of girls play organised sports in India.

Throughout the film, it is abundantly clear that she is incredibly uncomfortable with the media attention and press she has to do as a result of her talent. Awkward, shy and embarrassed of the attention she receives, there is an obvious ongoing struggle. Yet, there is an unwavering focus that has emerged and at the heart of her story is a contradiction to her shyness and modesty. “I always wanted to do something that got me noticed. So people would recognise me and say, ‘That’s Deepika”.

Since Rio, an elite archery academy is being built in Jamshedpur and Kumari has Tokyo 2020 in her sights. She revisits her old academy to speak to the group of girls giddy with excitement at her visit. She is the example and inspiration to them that didn’t exist for her, but while they already see her as a hero, it may well take Olympic gold – something billions haven’t managed before her – to convince a patriarchal society of the same.

Ladies First is available now on Netflix.

SaveSave