Nüshu: China's Historical 'Women-Only' Secret Script

Nüshu — literally “women’s writing” — was a secret script used by peasant women in a small region of Hunan province during the 19th and 20th centuries. Nüshu was exclusive to women and never taught to men. Its existence was virtually unknown to the general public until the 1980s. Who were these women who used nüshu, and why did they feel the need to invent their own clandestine script? Here’s a look at the subculture behind this fascinating piece of Chinese history.

Who used nüshu?

Nüshu was used by peasant women in Jiangyong county, Hunan province. Knowledge of the script was passed down from mother to daughter, and no men were able to read it, although they knew of its existence.

The script was used to communicate with intimate female relatives and friends in the midst of a highly patriarchal society. The regional cultural practice of establishing “sworn sisters,” or laotong, is a crucial part of this story. Laotong relationships were established between pairs of girls from the same village during childhood. Though not biologically related, the laotong relationship was expected to last for life – even after the girls married and moved to the homes of their husband’s families, which was frequently far away from their birth village.

These married peasant women lived highly circumscribed lives. They were usually kept indoors, doing needlework and household chores. As a result, the laotong relationship, which was kept alive by exchanging letters in nüshu, was a crucial and cherished companionship.

The discovery and study of nüshu

The existence of nüshu was almost unheard of outside of Hunan province until the 1960s, until an old woman fainted in a train station and was brought to the attention of the police. Among her belongings, the authorities discovered a document written in a mysterious code, and arrested the woman on suspicion of being a spy.

It wasn’t until after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution that the script was finally studied and documented, most notably by Zhou Shuoyi, the first man to master the script. Zhou began studying nüshu in the 1980s, and published the first dictionary of nüshu characters in 2003.

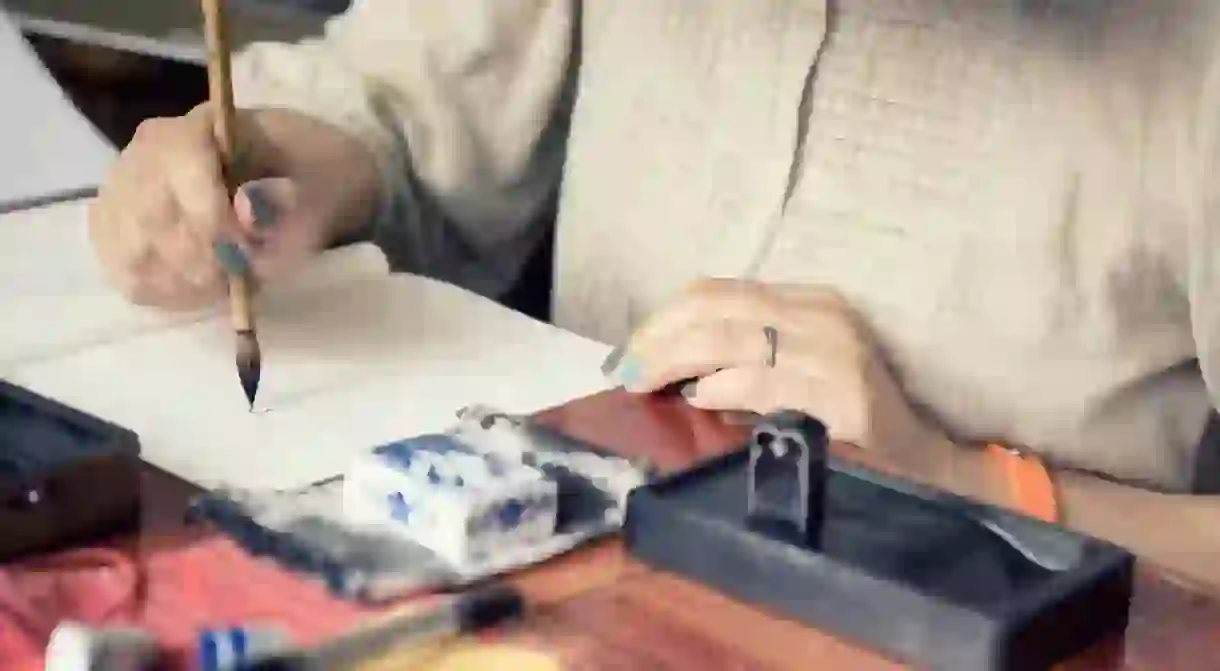

Records of nüshu calligraphy can be found in embroidery, such as handkerchiefs and quilts. It was also found on fans, letters, and autobiographical texts. One of the most common records of nüshu are sanzhaoshu, or “third day missives,” a cloth-bound book that is presented to a bride on the third day after her wedding day. The sanzhaoshu is written by the bride’s mother, female relatives and peers, and contains messages expressing hope for the bride’s future happiness and sorrow at her departure.

How the script works

The strokes that characterize nüshu are composed of dots, vertical lines and arcs. Like traditional Chinese texts, nüshu was typically written from top to bottom, with columns arranged from right to left. However, while standard Chinese characters (hanzi) represent meanings rather than pronunciations, about half of nüshu characters are phonetic, while the other half are modified hanzi.

Although nüshu has been called a “women’s language,” nüshu is a script, not a language. The women who used it wrote using the grammar and vocabulary of their local dialect, a variety of Chinese used in southern Hunan.

How nüshu fell into disuse

By the time scholars began to investigate nüshu in the 1980s, the script was already on the verge of extinction. By then, only about a dozen women could understand and write nüshu.

Cultural and social changes in 20th-century China gave women greater opportunities and freedoms, as well as access to education. Instead of nüshu, young girls in the Jiangyong region began learning hanzi instead, finding little use for the clandestine script used by their mothers and grandmothers.

The last person to be proficient in nüshu (excluding scholars who learn the script in order to study it), was Yang Huanyi, who lived in Jiangyong county. She died in 2004, at the age of 98.