Wealthy Collectors Bring China's Lost and Stolen Artwork Back Home

China’s rapid economic rise has given birth to a growing number of wealthy Chinese art collectors who are paying enormous amounts to ensure China’s stolen treasures are returned once and for all.

If auction houses are anything to go by, it would appear the new hobby for a growing number of rich Chinese is to purchase artwork and antiques in a bid to reclaim their nation’s heritage.

Back in 2011, a firm of small auctioneers in England made international headlines for the £53m sale of an imperial Qianlong vase to an anonymous Chinese buyer. This wasn’t a rare occurrence – in fact, over the past decade, it’s been happening everywhere as an increasing number of millionaire Chinese art collectors are dominating auctions on the hunt for stunning treasures. The message is clear – the Chinese want their stolen artwork back.

For many years, mainland Chinese state media has claimed that about 1.67 million Chinese relics are housed in more than 200 museums across 47 countries. In fact, the Chinese Cultural Relics Society said China had lost more than ten million antiques since 1840 due to wartime looting and illegal excavations.

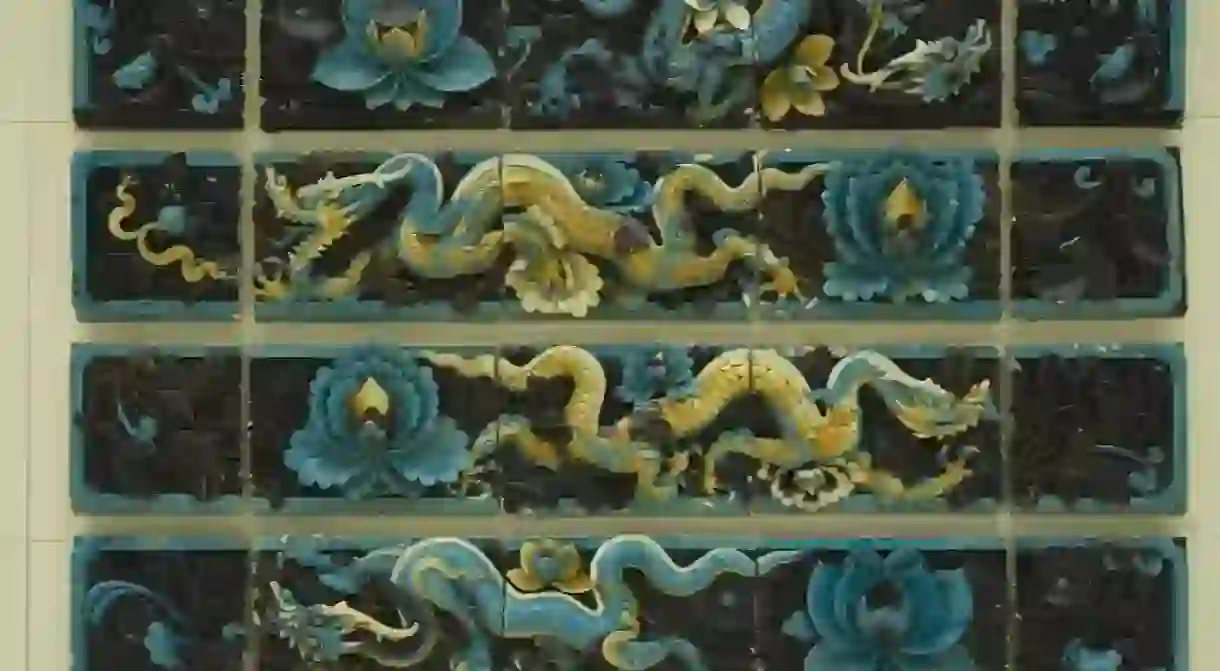

China likes to point the finger at its self-defined “century of humiliation,” from the Opium Wars of the 1840s and 1850s when French and British forces marched on the Old Summer Palace in Beijing and stripped the nearly thousand-acre site of sculptures, silk robes, jewellery and even Pekingese dogs.

However, China’s rapidly growing number of wealthy elite are eager to reclaim the country’s treasures. According to the Hurun Rich Report, as of 2016, China is now home to 609 billionaires, more than any other country in the world.

One example is taxi-driver turned billionaire, Liu Yiqian, and his wife Wang Wei who are among China’s top collectors. In order to house their extensive collection, they have even had to open their own ‘museums’. Together, they have established the Long Museum, which has two Shanghai branches that collectively house China’s largest private collection of art.

Others, although not of Chinese nationality, are also committed to returning Chinese treasures to China. Among them is American casino mogul Steve Wynn, who owns a number of high-end casinos in Las Vegas and two in Macau, China.

Wynn began collecting Chinese art objects in 2006 with a record-setting purchase of a red porcelain vase from China’s Hongwu period (1368-1398) for US$10 million at Christie’s in Hong Kong. Wynn later donated the vase to the Macau Special Administrative Region, where it entered the permanent collection of the Cultural Affairs Bureau’s Macao Museum.

In 2011, Wynn also purchased a set of four Chinese Qing Dynasty vases, named ‘Buccleuch Vases’, at Christie’s in London for US$12.8 million. The vases are now on permanent display inside his most recently opened Wynn Palace resort in Macau, China.

In the past, China itself has resorted to bidding in overseas markets to recover its lost national treasures.

In 2000, the Poly Art Museum, owned by the Chinese state-owned Poly Group, won the bidding at Christie’s and Sotheby’s auctions in Hong Kong for three bronze heads looted from the old Summer Palace in Beijing by British and French troops in 1860.

However, whilst China likes to paint the picture of itself as a victim of foreign attacks and attribute the loss of its cultural relics solely to these attacks, China’s claims are often inaccurate and grossly inflated. They tend to omit the huge part they played in destroying and looting their own treasures during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), when museums were ransacked, and countless antiquities destroyed.

After the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party organised what one dealer called ‘the world’s biggest garage sale’ of looted Chinese relics when foreign dealers from around the world were invited to bid for a vast depository of antiques.

However, having for decades viewed antiquities as relics of bourgeois decadence, the Chinese Communist Party has now done a complete u-turn and positioned itself as guardians of traditional culture. They now view cultural works as ‘a foundation for China to compete in the world’. Understandably, many foreign dealers and museum curators say they feel outraged by this latest twist in the Communist Party’s attitudes to the past. Some have labelled it as ‘the grossest hypocrisy’.

London’s British Museum is often named by The China Cultural Relics Society as a primary culprit for items looted from Beijing’s Summer Palace. In the past, the number of items they claimed the museum is holding has magically increased from 23,000 up to wild estimates of 230,000 items. However, of its 23,000-item Chinese collection, purchased from or donated by various sources over a long period, the British Museum maintains that just 15 pieces might possibly be of Summer Palace origin.

All in all, one thing is clear, there seems to be a reverse of flow with Chinese fine art and ceramics from America and Europe moving eastwards back to China. Not in years has there been such a vigorous redirecting of cultural artefacts from one part of the world to another, as European and American collections are broken up and sold off to the newly wealthy Chinese. Whether the art was stolen or not, it’s becoming a clear picture, the Chinese are on a mission to bring their lost heritage back home.