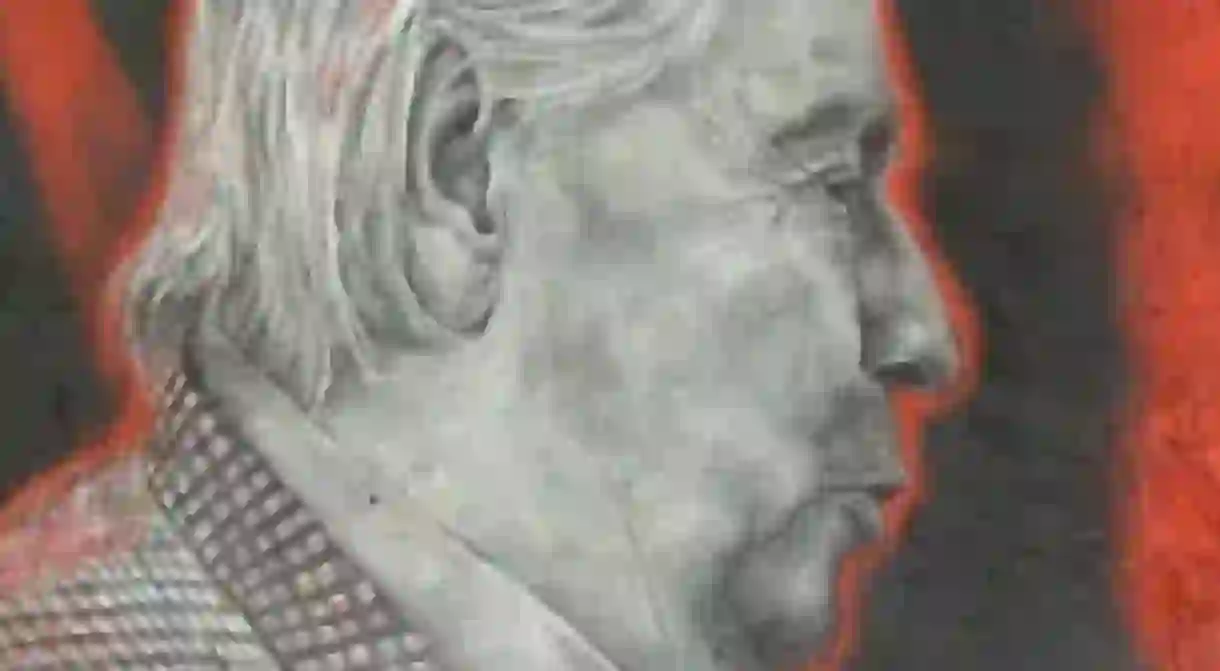

The Life And Work Of J. G. Ballard

James Graham ‘J.G.’ Ballard (1930-2009) was a prolific British novelist born and raised in Shanghai. Ballard is famous for his apocalyptic and, indeed, post-apocalyptic novels and short stories that engage with a new wave of science fiction, characterized by bleak man-made landscapes and the effects that technology, society and the environment have on the human mind. Ballard led a fascinating life full of change and unexpected turns, which included a stint of imprisonment in a POW camp during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai in World War II. It is, therefore, not surprising that his stories are noted for being avant-garde and often unpredictable.

Empire of the Sun, 1984

Arguably Ballard’s best and most famous novel, Empire of the Sun is a semi-autobiographical account of a young British boy’s experiences in Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese war. Ballard was raised in Shanghai’s international settlement where he lived due to his father’s work commitments as the chairman and managing director of the China Printing and Finishing Company. During the Japanese occupation of Shanghai (1937 – 1945), Ballard and his family were forced to leave their suburban home and live in the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Centre, a concentration camp for foreign nationals, for two years. Empire of the Sun is largely based on Ballard’s experiences in this camp although he exercised great artistic license in removing his parents from a large part of the narrative. The Guardian called it ‘the best British novel about the Second World War,’ and it was later made into a film, directed by Steven Spielberg and nominated for an Academy Award in 1987. This hard-hitting novel about the reality of war as seen through the eyes of a child exposed ‘the truth’ that Ballard felt lay beyond the sheltered confines of his privileged life of entitlement in the international quarters of Shanghai.

The Atrocity Exhibition, 1969

After the sudden death of his wife Helen Mary Matthews in 1965, Ballard began writing a collection of short stories that became The Atrocity Exhibition. With no clear beginning or end within the plot, the book jarred many with its unpredictable style of storytelling, switching protagonists and narrative outlook in each chapter. The essays turn the harrowing and significant cultural stories of the time into subjects that are relatable to the everyday person, but in an absurd and challenging way. These include approaching the assassination of John F. Kennedy as a sexual or sporting event, the eroticization of then-Governor of California Ronald Reagan, and Marilyn Monroe’s suicide. All of Ballard’s essays in this collection had previously been published elsewhere, but surprisingly, this hardly subdued the shock and controversy that surrounded the book, which later was the subject of a lengthy obscenity trial. Indeed, Doubleday USA destroyed almost an entire print run before distribution, fearing legal action from some of the celebrities featured in the book. Despite the controversial content, the book won the Guardian Fiction Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.

Crash, 1973

Elaborating on a story and idea originally conceived in The Atrocity Exhibition, Crash explores the sexual potential of car crashes with the eroticization of machinery and subsequent consequences of arousal. Ballard furthered his fascination with this subject through a short film that he made with the actress Gabrielle Drake and an art installation of cars. Several details of the book caused many to draw parallels between author and character. The novel’s protagonist is named James Ballard who lives in Shepperton, the Surrey town that Ballard made his home in 1960. While other biographical details do not necessarily mirror the author’s personal life and history, comparisons between the fictional and real James Ballard were heightened as the author was involved in a serious car crash shortly after this novel’s publication. This controversial novel focuses on how the mechanization of the world can lead to man’s demise through his own inventions. David Cronenberg made it into a film in 1996, which British tabloid The Daily Mail called for to be banned.

Vermillion Sands, 1971

This short story collection is set in the eponymous desert resort inhabited by foreign celebrities, heirs, artists and the merchants and servants who work for them. This collection is a critique of society as Ballard saw it, featuring exotic technology such as cloud-carving sculptures, poetry-composing computers, singing orchids and canvases that paint themselves. The inventions all service dark, hidden human desires with grotesque psychological and physical results. Ballard claimed that the collection celebrated the ‘neglected virtues of the glossy, lurid and bizarre.’ This collection pushes the boundaries of science fiction to the point that many of the inventions that were futuristic in 1971 are now a reality. Therefore, this collection can be unsettling for the modern reader as they can see their world reflected in this dystopian setting.

Kingdom Come, 2006

Ballard’s final published novel aspired to blur the line between consumerism and fascism, using populist politics and the deculturalization of middle-class suburbs as vehicles for a ‘new order’ in modern-day England. The novel’s protagonist, Richard Pearson, begins to investigate after his father is murdered in a day-time shooting spree at the local Brooklands Metro-Centre Mall, which has of late become overrun with a new element of clientele who are highly nationalistic and rabidly pro-sport. There are few if any easy answers for Pearson as to what caused his father’s death, and the entire novel instead takes on a tone of characteristic Ballard apocalyptic forewarning about an evitable and ethereal lurch of collective morality that may exist ahead of us in the not so distant future.

By Madeleine Parsley