Profiling Ieoh Ming Pei | China's Best-Known Architect

Ieoh Ming Pei is one of the most celebrated and prolific architects of our time. Pei has designed some of the most iconic buildings and extensions around the world and has won numerous awards for his unique modernist architectural vision. Culture Trip reviews his impressive career and most important works.

When the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) awarded its Royal Gold Medal to I. M. Pei in 2010, RIBA President Ruth Reed commented: “The Royal Gold Medal has been called, often erroneously, a lifetime achievement award. Seldom has it been so true as it is in the case of I.M. Pei. At 92 he is that rarity; an officially retired architect, though there is still work in the pipeline to be delivered, work that will crown the extraordinary achievements of six decades in which he has reinvented the housing, gallery, and commercial building types. He is truly an inspiration for all architects.”

Born in 1917 in Guangzhou, China, I. M. Pei earned a B.A. in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1940 and a Master’s in architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1946, where he studied under German architect Walter Gropius, a pioneer of modernist architecture and founder of the Bauhaus school.

After seven years as director at the real estate development corporation Webb & Knapp, Pei founded his own firm in 1955, now Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. Pei’s partnership received the 1968 Architectural Firm Award of the American Institute of Architects. Since retiring from full-time practice in 1990, he has been working as an architectural consultant primarily for projects outside the United States, from his sons’ architectural firm Pei Partnership Architects.

Pei received many awards and recognitions throughout his career, including the Pritzker Prize in 1983, with a jury citation stating that he “has given this century some of its most beautiful interior spaces and exterior forms.” Pei used his $100,000 prize to establish a scholarship fund for Chinese students to study architecture in the United States, and then return to China to practice their profession.

Pei was also elected an Honorary Academician of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1993 and received various honorary doctorates, including from Harvard University, Columbia University, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the American University of Paris and the University of Rome, among others.

Modernist Localism

Although a member of the modernist generation, Pei has stood out for rejecting the implications of globalism inherent in the International Style of architecture that emerged in the 1920s and 1930s; a key movement of the formative decades of modernist architecture. The most common characteristics of the style, evident also in Pei’s work, are rectilinear forms; light, taut plane surfaces stripped of ornamentation and decoration; open interior spaces; and a visually weightless quality reflected by the cantilever construction. The favored materials are glass and steel, with a combination of less visible reinforced concrete.

Pei adapted to the style’s characteristics, but instead of creating globally homogenized structures, he advocated contextual development and variation in style, inspired by the locality and the purpose of a project. Pei told ArchDaily that “the important distinction is between a stylistic approach to the design; and an analytical approach giving the process of due consideration to time, place, and purpose.” The Pritzker Prize citation also wrote of the architect: “His concern has always been the surroundings in which his buildings rise.”

When he first returned to China in 1974, to design the Fragrant Hills Hotel, which was completed in 1982, Pei urged Chinese architects to take inspiration from their architectural traditions, rather than just emulating the West. The Hotel, located in a public park in the former Imperial Hunting Grounds outside Beijing, includes a central skylight space that preserves the existing ancient trees, with 325 rooms zigzagging out from it, in a balance of symmetry and asymmetry.

Intimately merging building and gardens, interior and exterior, the hotel features individual rooms, in which a ‘window picture’ framing the landscape opens onto the courtyard. Advanced Western technology is combined with Chinese vernacular architecture, avoiding literal imitation: all built by local craftsmen with age-old materials and techniques, the only imported element was the skylight. With this project, Pei contributed to forming a distinctly Chinese style of modern architecture that can be applied to a variety of buildings.

In the Luce Memorial Chapel (1963) in Taiwan, originally conceived as a wooden structure, the concrete beams, thicker at the base and tapering towards the tip of the tent-like design, form a latticework on the inside walls of the chapel. Its architecture combines complex technology and advanced engineering with a modernist aesthetic expression through its irregular hexagonal base and curved planes, adapted to the humid and seismic conditions and the landscape of its location. The structure evokes Le Corbusier’s Philips Pavilion at Expo ’58 in Brussels.

Other examples of Pei’s adaption of modernist architecture to local context and purpose are the Shinji Shumeikai Bell Tower and the Miho Museum in Japan; the Suzhou Museum (2006) in China; the Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art (MUDAM) (2006); and the Museum of Islamic Art (2008) in Doha, Qatar.

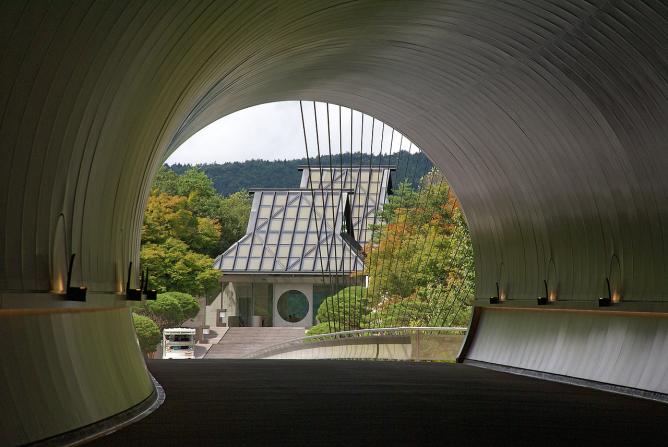

In the 1990s, Pei worked on two projects in Japan for a new religious movement, the Shinji Shumeikai, whose leader, Kaishu Koyama, approached him to design a bell tower and museum. Given artistic freedom, Pei explored their beliefs in order to reinterpret them in his project: the final 60-meter tower resembled the bachi used for playing traditional instruments like the shamisen. The second project was the Miho Museum, a French limestone and glass roof structure completed in 1996 on a scenic mountainside in a nature preserve near Shigaraki, which houses Koyama’s collection of tea ceremony and historical artifacts from the Silk Road. The difficult location of the project led Pei to incorporate the architectural structure in the mountain: he built a tunnel through a mountain leading up to the museum via a bridge suspended from 96 steel cables, while 80 percent of the building is located underground. Pei’s mountain tunnel was partly inspired by a story from 4th Chinese poet Tao Yuanming.

The Suzhou Museum, Pei’s only other project in mainland China, opened to the public in 2006, and was seen as a second chance by Pei, who told The New York Times that the Fragrant Hills Hotel was a disappointment, commenting: ‘I was saved by the trees.’ Suzhou has a personal significance for Pei, whose grandfather had a house there that he would visit during the summer, so accepting the Suzhou government project came naturally. The large white stucco museum is situated on hallowed ground adjoining a complex of historical structures and two gardens listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Pei used grey and white, ‘Suzhou colors’, combined with a modern structure, commenting, “[In China] architecture and the garden are one. A Western building is a building, and a garden is a garden. They’re related in spirit. But they are one in China.”

MUDAM, Luxembourg, opened in 2006, serves as another example of Pei’s adherence to the adaptation of a design to its context. With an asymmetrical V shape, a glass topped bell turret and another octagonal wing, the museum rises over the ruins of a fortress. The new, formalist structure not only reflects the ancient, but blends with it; its monumental, geometrical volumes becoming an extension of the past.

Launched in 2008, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha is inspired by ancient Islamic architecture, particularly the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo, and is situated on a stand-alone island off the Doha Corniche and surrounded by a park. Pei’s Louvre collaborators Wilmotte & Associates designed the interior spaces. Both exterior and interior, including the surrounding park, juxtapose modern aesthetics with the traditional symmetry of Islamic geometric designs, and present a fluidity between the natural surroundings and the artificially created spaces.

A Futuristic Vision

Pei’s most well-known work worldwide is probably his underground extension to the Louvre in Paris, including the crystal pyramid. It is one of many that adopt a ‘futuristic’ vision, brutally breaking from tradition. Originally a point of controversy after its completion in 1989, the pyramid has been accepted over the years and is now hailed as one of his most iconic projects. Pei said: “Formally, [the pyramid] is the most compatible with the architecture of the Louvre … , it is also one of the most structurally stable of forms, which assures its transparency, as it is constructed of glass and steel, it signifies a break with the architectural traditions of the past. It is a work of our time.”

The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, opened in 1990, was the tallest building in Asia until 1992 and is still one of the tallest in Hong Kong. At 70 stories high, the asymmetrical steel and glass tower holds strong symbolic meaning for the Chinese people and goodwill towards the British Colony. Inspired by bamboo, a symbol of hope and revitalization in China, the trunk of the building emulates the growth patterns of the plant, reducing its mass towards the top. The composite structural system also resists high winds and eliminates the need for many internal vertical supports, a usual requirement in the typhoon-prone location.

The JFK Presidential Library (1979) at Columbia Point peninsula in Boston has been said to exemplify an ‘architectural presence representing both memorial and monument.’ With Pei’s play of space and light, and his iconic geometric structures, the library’s understated form comprises a singular and brilliant triangular tower protruding from an expanding base of geometric forms, with a cube of glass and steel rising along with the tower.

The East Building of the National Gallery of Art (1978) in Washington DC was designed to reflect the trapezoidal form of the plot it stands on. Pei started from two triangular sections, and used the isosceles as a unifying motif of the building, in the marble floors, steel frame and glass skylights. Other triangular forms are repeated in a variety of elements, while the interior features softened, rounder lines. In the plaza between the East and West Buildings are glass pyramids referencing the East Building’s ceiling. The pyramids subsequently became a trademark of Pei’s museum designs, as seen in the Louvre.

The Macau Science Center (2009), a distinctive asymmetrical conical-shaped structure with a metallic finish, is the most futuristic looking of Pei’s designs, and includes a planetarium, 3D projection facilities and Omnimax films. The main building’s interior has a large atrium and a spiral walkway, from which galleries lead off, mainly consisting of interactive exhibits for science education.

I. M. Pei has contributed to elevating architecture to a unique and individual form of artistic expression, while creating a harmonious relationship with its surroundings and its social function. Pei said in his acceptance speech for the 1983 Pritzker Prize: “I believe that architecture is a pragmatic art. To become art it must be built on a foundation of necessity.”

By C. A. Xuan Mai Ardia