How to Look at a Calligraphy Painting

In China, calligraphy is not only appreciated as art but also as a way to reveal the character of the artist. There is a famous saying that goes “The writing reveals the writer.” The way a calligrapher chooses to draw his or her characters speaks about cultivation, temperament, education, and more. Dating back to as early as 4000BCE, calligraphy has developed into a literati pastime that transcends the text itself.

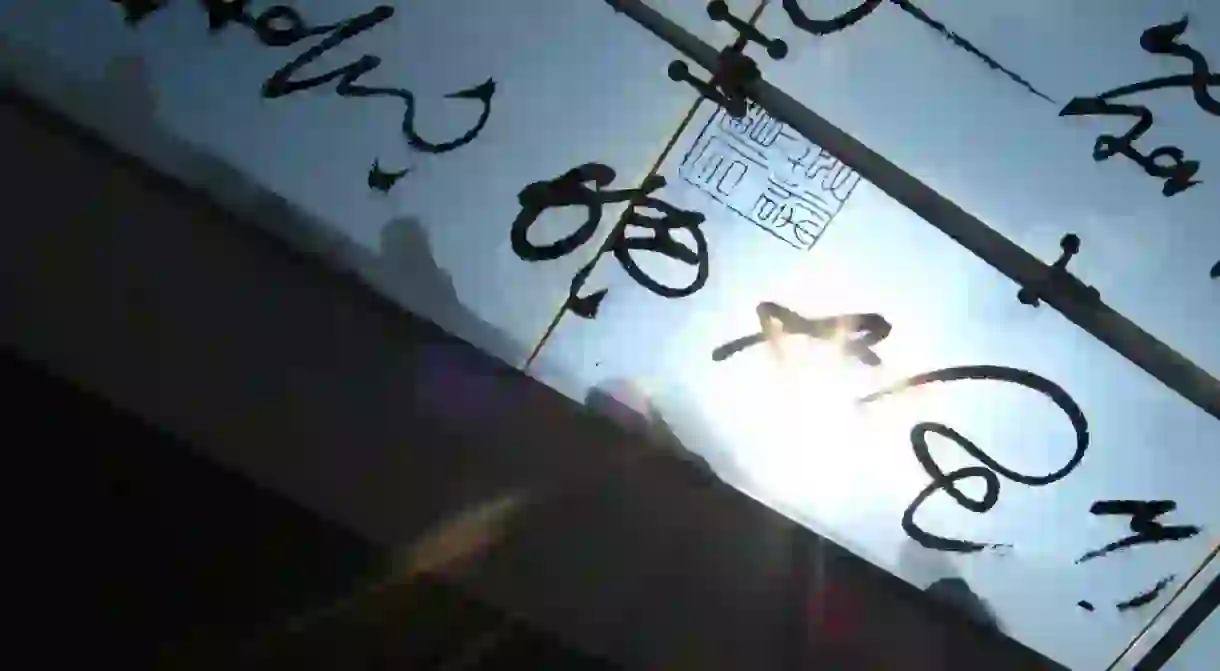

The first thing to understand about Chinese calligraphy is that it is typically written top to bottom and right to left, with the artist’s signature stamped in red at the end of a thought. While each calligrapher has his or her own style, there are five main categories of traditional calligraphy: Xing, Cao, Zhuan, Li, and Kai.

Xing refers to semi-cursive, or running, script and was developed in the first century CE. It is not far off from regular script and is therefore legible to any literate Chinese. Perhaps its most famous proponent was the Jin dynasty (CE265-420) writer and calligraphy master Wang Xizhi.

Cao

Full cursive script is known as Cao calligraphy. Because the script is not designed to be legible, it is appreciated primarily for its artistry. The style originated during the Han dynasty (206BCE-220CE) as a shorthand way to write clerical script but quickly evolved into an aesthetic choice. It is the basis for the Japanese hiragana alphabet as well as some simplified Chinese characters.

Zhuan

Zhuan calligraphy, also known as seal script, is the earliest form of Chinese calligraphy that is still in practice today. It utilizes a much earlier form of Chinese characters, evolved from the Oracle Bones, that is more akin to a pictograph than is the modern logographic script. It evolved out of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256BCE) writing system and was popularized on seals during the Qin dynasty (221-206BCE), thus its name.

Li

Nearly as old as the Zhuan script is the Li, or clerical, style. Its characters look like a mix between the ancient pictographs and the modern, regular script, thus it is favored today for its somewhat legible artistry. It simplified the more complicated strokes of the seal script and applies more angular turns. It is one of the parent systems to the Japanese kanji alphabet and may have first been written by prisoners conscripted as scribes.

Kai

Kai calligraphy is the regular script. Developed towards the end of the Han dynasty (206BCE-220CE), it is still in common practice today, some 1800 years later. Although it came to maturity during China’s most poetically prolific dynasty, the Tang (618-907CE), it is now seen as a more utilitarian script. It, along with the Xing, are now used in everyday contexts, whereas the Cao, Zhuan, and Li are reserved for art.