Mzungu Kichaa: Bongo Fleva's Adopted Son

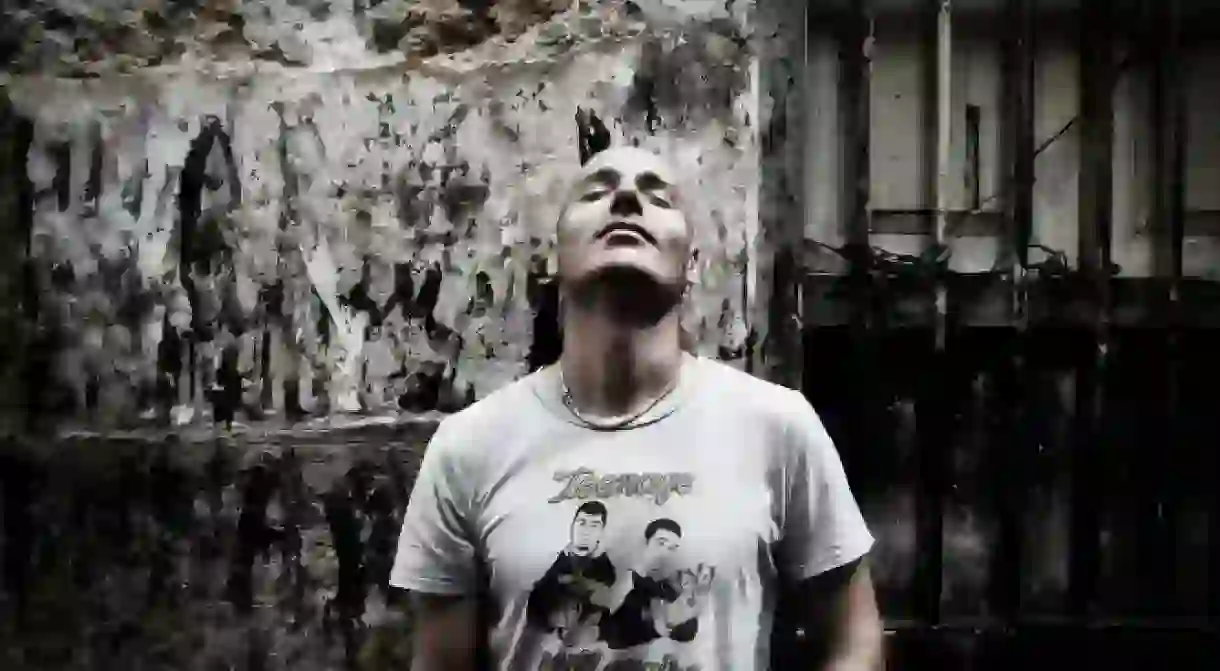

Espen Sorensen, better known as Mzungu Kichaa (the “crazy white man”), has spent time living in Copenhagen, Dar es Salaam, and London. He embodies a blend of these various places that has resulted in him becoming what he is today: one of the pioneers of East Africa’s most popular fusion of traditional music and hip hop: Bongo Fleva.

‘Ukiwa na uwezo siyo lazima uwe kichaa’ (‘no need to be crazy if you can do it’) says Kichaa in the track Oya Oya, and he is right with his self-assessment. He has proven he can indeed do ‘it’ and has been for quite a while. Laying the foundations to his success with degrees in Ethnomusicology and African Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, Kichaa has climbed high up the ladder of Tanzanian artists since his beginnings in the music industry. His first album, Tuko Pamoja was released in 2009, and was followed up by a tour of several East African and European concert venues and festivals. He is an advocate of Tanzania’s contemporary music scene and aims to make Bongo Fleva known across Tanzania’s borders as he considers it music that ‘can open our minds and expand our horizons.’

Kichaa writes his songs in Kiswahili, the lingua franca of East Africa, and Tanzania’s official language (the only African country with a non-colonial language as their first recognized means of communication). The pride connected to the use of the language is reinstated throughout Kichaa’s music, as his Swahili rhymes flow as perfectly as any native’s. By speaking another language, you also enter a different weltansicht: another view of the world. Kichaa has managed to do exactly that, to take on a perspective that reflects the experiences, struggles and happiness of a different culture by describing and singing about it in its own language, its unique means of expression. His songs are made for dancing, going straight into your bones letting you not only hear but also feel what he is speaking about, in case you may not be fluent in Swahili like him. His message: the quest for an end to any kind of inequality, and the need for staying pamoja (together) in this world. His lyrics are critical and thought provoking, contesting generalized and non-reflective images of what is happening in the world. “Maendeleo hayana muelekeo” he tells us in Jitolee, that development does not have a linear direction and with that deconstructing the common use and universalized and somewhat westernized evolutionary, understanding of the development concept that until now has mostly led people nowhere.

As a caucasian male in his early 30s making Tanzanian music, Kichaa’s heritage is probably one of the most obvious things one could be confused about when his lyrics are in Swahili, however, most of the other artists he is surrounded by are natives from African countries. This implies no contradiction as his efforts show what is truly essential to making music. Neither the colour of your skin nor the country you were born in are relevant. Transporting messages that are not rooted in or bound to a particular space, but that could stem from everywhere and that put an emphasis on respecting each other and building on our common humanity – free of locality. Kichaa creates a concept of belonging that revolves around belonging to people, to your friends and loved ones, and not to some narrow concept of nationality. Belonging as a feeling and not as an obvious and logical rationality is what his music and his alias represent.

A different approach to building bridges between those often displayed as ‘the others’ and those who appoint themselves the role of deciding who that is. Kichaa has freed himself of assumptions that dictate the game, sticking to his own rules but relying on common principles of living together in peace and with respect – regardless of any defining factors such as ethnicity, gender or age. Kichaa might be suggesting an alternative approach to eliminating persisting walls between people due to the categories mentioned above. He does not do that dressed up as one of the all-knowing development organizations, but simply with his personality and skills. This individual approach to creating unity and eliminating boundaries between people seems to work. The Tanzanian music scene has embraced and acknowledged him as one of their own – something that does not often happen towards ‘crazy white men’.