Rhythmical Resistance: Musicians from the Apartheid Era

If anything good came from apartheid in South Africa, it was the music that was created in opposition to it.

Every aspect of life in South Africa was influenced by apartheid; culturally, music functioned as a popular initiative and response to the political repression of that era. As a result, apartheid shaped the lyrics, tones, and styles of most African music produced during this era, leaving in its wake a class of performers who produced some profoundly moving and powerful music that both helped to unite black Africans, and educate people around the world of the dire political circumstances.

Though there is a long list of musicians who used their music, and popularity, to push back against political oppression, a few in particular stand out. Hugh Masekela, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, Johnny Clegg and Brenda Fassie were artists who used their music to campaign against the profound injustice of apartheid, and continued to enjoy global recognition long into the new democratic dispensation.

As revealed in Anne Schumann’s essay, The Beat that Beat Apartheid: The Role of Music in the Resistance against Apartheid in South Africa, music initially started as a mirror reflecting the popular experience. However, as time went on and resistance movements started to emerge, music and creative expression started to become a hammer with which to “shape reality.” In this sense, music in South Africa went from “reflecting common experiences and concerns in the early years of apartheid” to “eventually functioning as a force to confront the state and as a means to actively construct an alternative political and social reality.”

During the apartheid era, it was difficult for black musicians in South Africa to perform, especially as a means of formal employment. Black musicians were not seen as equals and were denied opportunities and rights. At the same time, performances by white musicians who were outspoken about apartheid, or those who performed alongside black musicians, were often subject to police raids. However, their talent and music was indeed still heard; many of these musicians fought hard to oppose the political limitations, and their resistance is a vital part of the story of South Africa’s resistance and recovery during and after the apartheid years.

Hugh Masekela: The Man With The Horn

Born in Witbank, South Africa in 1939, Hugh Masekela was a South African flugelhorn, trumpet and cornet player who performed in numerous jazz ensembles around the world. Masekela was inspired after watching the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn, where Kirk Douglas plays an American jazz trumpeter. He was first given a trumpet at the age of 14, from Trevor Huddleston, a British anti-apartheid archbishop working at his township school. He quickly mastered the instrument, and along with others at his school formed South Africa’s first youth orchestra.

His solos have been incorporated into the framework of pop, R&B, disco, Afro-pop, and jazz music, and he toured with many renowned musicians such as Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix and the Byrds.

Masekela’s interest in his African roots instigated a collaboration with other African musicians during Paul Simon’s controversial Graceland tour. His music was also featured in the Broadway play Sarafina!, and he appeared in the documentary Amandla! A Revolution in Four Part Harmony. He won two Grammy Awards, with his albums Grazing in the Grass and Sarafina!, and wrote, recorded and performed several international hits. His 1987 single Bring Him Back Home was written as an anthem accompanying the movement to release Nelson Mandela from prison.

Interestingly, Masekela didn’t start out to make a political statement, but rather his music became linked to the fight against apartheid because of where he came from, and the fact that he would inevitably find inspiration from his people and his country.

His political profile escalated in 1961 when he was exiled from South Africa to the United States, returning only after apartheid had ended in 1990 with a musical style that is now best described as African jazz. Capable of “outstanding ballad and bebop work,” Masekela was not only a charismatic musician, but also an important icon in relation to apartheid times. He died in Johannesburg in January 2018 after a protracted battle with prostate cancer. At the time of his death, then-South African president Jacob Zuma paid moving tribute to the musician. He said, “His contribution to the struggle for liberation will never be forgotten. We wish to convey our heartfelt condolences to his family and peers in the arts and culture fraternity at large. May his soul rest in peace.”

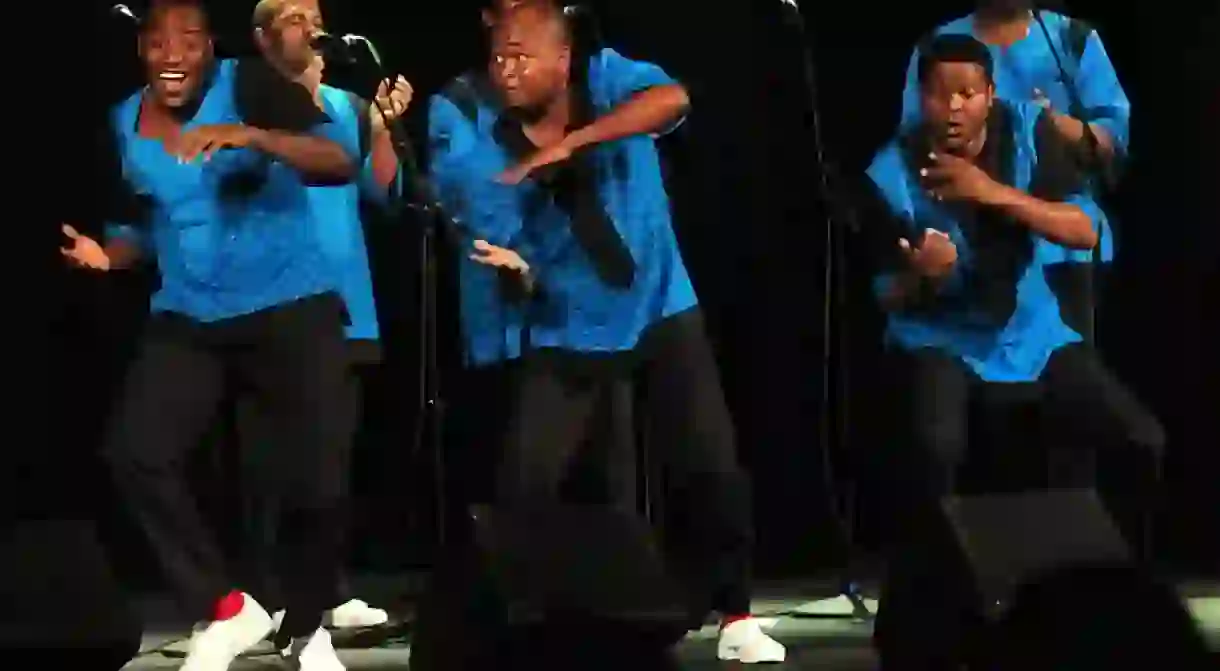

Ladysmith Black Mambazo: Zulu Chorus

The voices of the male choral group Ladysmith Black Mambazo have come to represent another example of traditional South African culture, specifically through their fusion of Christian gospel music with unique African rhythms and harmonies. They are considered something of a national treasure in South Africa, and are celebrated around the world.

Their name is an interesting hybrid of founder Joseph Shabalala’s background: ‘Ladysmith’ being the town of his birth in KwaZulu-Natal; ‘Black’, a reference to the black oxen, the strongest of all farm animals and a tribute to his life on his family’s farm; and ‘Mambazo’, the Zulu word for axe that Shabalala says is “a symbol of the group’s vocal strength, clearing the way for their music and eventual success.”

They were formed in Durban in the 1960s by Shabalala, and today they are revered as one of South Africa’s most exciting groups. Regardless of the listeners’ faith, Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s music instigates enthusiasm through the sheer power and quality of their combined vocals. The group first found fame in 1970, and their discography currently contains more than 50 albums.

Even though they are popularly referred to as entertainers, staying true to their musical heritage is an important aspect of their performances; they do this by drawing from traditional South African mine music called ‘isicathamiya’, and South African acapella called ‘mbube’.

They were rediscovered by Paul Simon in the 1980s, and their collaboration in 1986 for Simon’s album Graceland received a Grammy Award for Album of the Year and catapulted the band onto the international stage. This album was considered a landmark in terms of introducing world music to mainstream audiences, as well as connecting the diverse mix of musical styles that it featured.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s first U.S. release, Shaka Zulu, also won a Grammy Award, and since then they have collected five awards and 17 nominations from the Academy.

In 1993, when apartheid was abolished and Nelson Mandela was released from prison, they came out with the album Liph’ Iqiniso, which celebrated the end of apartheid, especially in the album’s last track, Isikifil Inkululeko (Freedom Has Arrived). Ladysmith Black Mambazo then accompanied Mandela to the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo, Norway and sang at his inauguration in 1994.

The group continued to release a multitude of albums reflecting their experiences, including Long Walk to Freedom, which celebrated the 45 years of their musical career. Accompanying this album was a night where musicians such as Sarah McLachlan and Natalie Merchant were guest performers.

Now, leader Shabalala has set up the Ladysmith Black Mambazo Foundation, so that Zulu youth have a chance to learn about their traditional culture and music.

Miriam Makeba: Mama Africa

Miriam Makeba was a legendary South African singer and civil rights activist, and an example of what Schumann deems the “hammer” in the way she actively spoke out against the realities of apartheid; The Guardian called her “one of the most visible and outspoken opponents” of the regime.

Makeba started performing to small audiences in her home township, but her music quickly launched her into celebrity status, both in South Africa and abroad. In 1954 she featured as a vocalist for the Manhattan Brothers, which led to her winning the role of the female lead in the show King Kong in 1959. In 1966, she became the first African artist to receive a Grammy Award, for her album An Evening With Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba. However, her popularity cost her her South African citizenship, forcing her to take asylum in Guinea where she became extremely active in the United Nations General Assembly, regularly speaking out about apartheid and the political situation in South Africa

Makeba also appeared in the 1960 anti-apartheid documentary Come Back Africa. In 1967 she gained even more recognition with Pata Pata, and soon after published her autobiography, Makeba: My Story, where she revealed tragedies and injustices she faced throughout her life.

Makeba’s experiences led her to be extremely involved with the black consciousness movement, and she met and married Stokely Carmichael, the leader of the Black Panthers – though they divorced after five years. Similarly to Hugh Masekela and LadySmith Black Mambazo, Makeba also performed with Paul Simon on his Graceland album and tour, and is widely regarded as one of the most important musicians of South Africa’s apartheid era.

Johnny Clegg: ‘The White Zulu’

Although the son of an English father and Zimbabwean mother, Johnny Clegg became one of South Africa’s most popular and influential musicians – both during and after apartheid. Clegg, often called ‘The White Zulu’, moved to South Africa at the age of seven, and thanks to his step father’s profession as a crime reporter, he received early exposure to township life, an insight few white South Africans had at the time.

At the height of apartheid in South Africa, Clegg met migrant worker and street musician Sipho Mchunu in the 1970s, and together they formed the band Juluka. Their catchy brand of pop music, sung in both Zulu and English, immediately caught the attention of the government at the time, and they were barred from public performances. Much of their music spoke to the political situation at the time, in particular about migrant labour and the divisive nature of apartheid.

Together, the two musicians were a powerful symbol of resistance against the draconian apartheid laws, and their performances were often the subject of police raids.

Juluka eventually split in the mid-80s when Mchunu returned to what is now now KwaZulu-Natal. Clegg went on to achieve even greater success with his new band, Savuka. He continued to perform his politically charged music with Savuka right up to the end of apartheid in the early 90s, at which point he shifted his commentary and involvement towards other social and humanitarian issues.

Brenda Fassie: ‘Madonna of The Townships’

Brenda Fassie, often simply known as MaBrr, or hailed as the ‘Black Madonna’, was one of South Africa’s most iconic musicians during apartheid. Although her career was mired in controversy, owing to a public struggle with drug addiction, her sheer talent and role as an outspoken musician under apartheid afforded her legendary status.

Fassie was the daughter of a pianist, named after American country singer Brenda Lee, and began busking to tourists from a young age. This strong musical foundation led to a successful career at the age of just 16, when word of a young woman in the Cape with a powerful voice spread throughout the country.

Fassie moved to the Johannesburg township of Soweto – one of the centres for resistance against apartheid – in order to further her musical career, and she soon became a household name. In spite of the seemingly jovial nature of many of her songs, she was unafraid to speak out against the injustices of apartheid.

While apartheid was at its most intense, and even during the early days of transition to a democratic government, Fassie raised a middle finger to society – earning her dramatic record sales and constant attention from tabloids.

Although she would eventually succumb to her drug addiction in 2004, her first recorded and arguably most iconic song, Weekend Special, is still one of South Africa’s most powerful.

This article is an updated version of a story created by Sarah Mitchell.