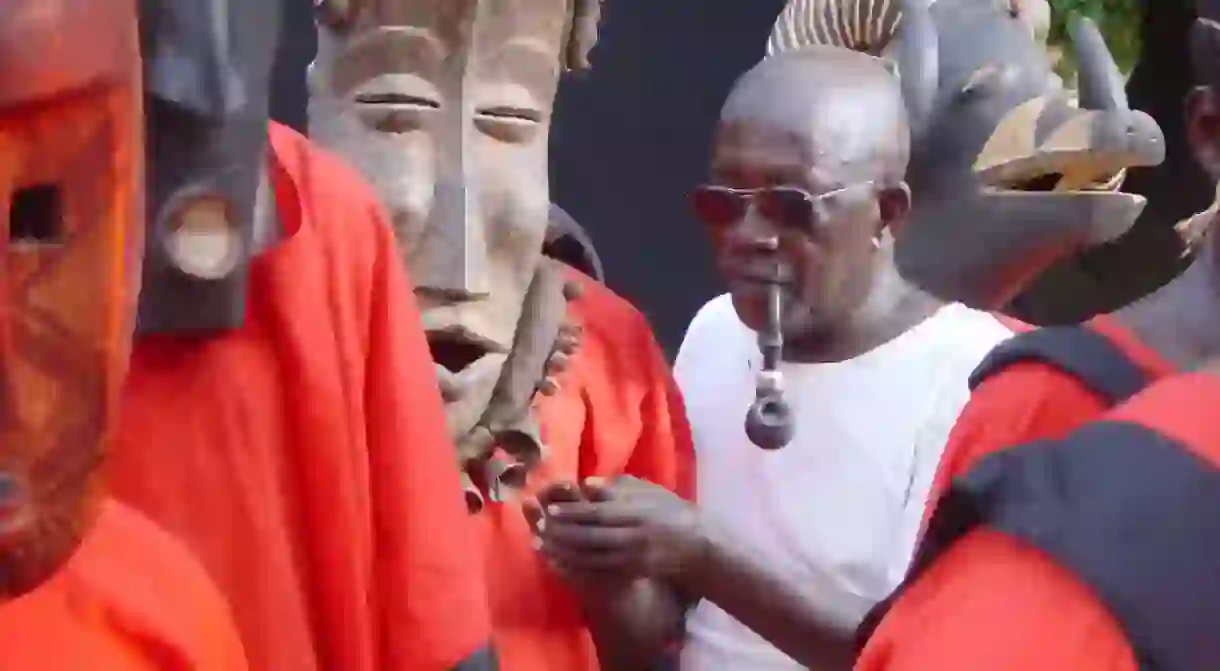

Why Ousmane Sembène is Considered the ‘Father of African Cinema’

A revolutionary filmmaker and writer, Ousmane Sembène used both pen and camera to return African stories to African people. Battling racism, censorship and language barriers, he transformed Senegal’s and Africa’s cultural output. This is the remarkable story of how Sembène became the ‘Father of African Cinema’.

Early years

“Bread came wrapped in French newspapers. Each time my father unwrapped a baguette, he asked me to read to him” – Ousmane Sembène

Born the son of an illiterate fisherman in Ziguinchor in 1923, Ousmane Sembène was not destined for the life he led. Expelled from school aged 13 for striking his white teacher, it was surprising he could even read French, let alone pen ten published novels in the language. But Ousmane Sembène was nothing if not determined. Following his expulsion, he was sent from Casamance to stay with his father’s relatives in Dakar. Here he took on jobs as a plumber, bricklayer and mechanic, spending much of his down time in segregated cinemas. In 1944, he was drafted into the French army, serving in both Europe and Niger, where he witnessed “those who considered themselves our masters naked, in tears”, before heading back to Dakar and participating in the Senegalese General Strike of 1946 that crippled the colonial economy. Both experiences would harden his anti-colonial resolve.

Finding his voice

“It was time for Africa to speak for itself” – Ousmane Sembène

In 1947, Sembène left Senegal to work as a docker in Marseille, where he joined the left-wing trade union movement and began to write poetry for French worker’s periodicals, before publishing his first novel, Le Docker Noir (‘The Black Docker’) in 1956. The novel fictionalised a dock strike he was involved in, but it would be the retelling of another real-life strike – the 1946-47 Dakar-Niger railroad strike – that would prove to be his seminal work.

Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu (‘God’s Bits of Wood’) laid bare colonial mistreatment and championed the strength of community in face of oppression. It was indicative of the unflinching, direct style for which he would become known. It realised a goal of telling African stories from African perspectives. There was just one problem: 80% of the Senegalese population were either illiterate or had no access to books.

The move to film

“Africa is my audience, the west and the rest are markets” – Ousmane Sembène

His message limited by the medium, Sembène resolved to change his megaphone and in 1962 he took up a scholarship at the Gorsky Film Institute in Moscow. A year later, he produced Borom Street, a short film about a taxi driver wronged by the new African bourgeoisie, which is regarded as the first film made in Africa, about an African, by an African.

His first feature film, La Noire de… (‘Black Girl’), which told the story of an African servant girl’s isolation working for a French family, brought him international recognition on its release in 1966, but it was his 1971 film Mandabi (‘The Money Order’) that would see him achieve a personal dream.

For Sembène, language and culture were inextricably linked, making it impossible to satisfy his desire of returning African stories to Africans while the dialogue was in French. Mandabi was in Wolof. A Senegalese story was being filmed in a Senegalese language for the very first time. Sembène would follow this up with Emitaï, much of which was filmed in the Diola language of Casamance, while he also toured the country, putting on screenings in remote villages to ensure as wide an audience as possible.

Themes of his work

“It was then necessary to become political, to become involved in a struggle against all the ills of man’s cupidity, envy, individualism, the nouveau-riche mentality, and all the things we have inherited from the colonial and neo-colonial systems” – Ousmane Sembène

A writer at heart, Sembène successfully transferred his iconoclastic message from paper to tape, taking on all forms of the establishment. From traditional African chiefs (Niaye) and the Islamic religion (Ceddo and Guelwaar) to the post-colonial Senegalese Government (Mandabi) and the actions of the French Army during World Word II (Emitaï and Camp de Thiaroye), none were spared from Sembène’s critical lens. Even Senegal’s revered first President, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was criticised, with Sembène pronouncing him a “great poet in the French language, but a poor politician”.

Sembène’s films racked up bans as rapidly as they did awards, but his subtle comedy would often evade the censors. In particular, his most well-known film, Xala (‘Impotence’), portrayed a ruthless African businessman, who is struck down with impotence on his wedding day because of his greed. The film carefully satirised the corruption of the post-colonial government, who were the principal financiers.

Meanwhile, he would champion the importance of women. Having been raised by his maternal grandmother, he had been a critic of patriarchy all his life, believing that “when women progress, society progresses”. As such, he was determined that “our forefathers’ image of women must be buried once for all”, with his final two films looking at women’s place in modern society (Faat Kiné) and female genital mutilation (Moolaadé).

Influence and legacy

“My aim is to make a film for Africans. And, if it’s done well, people will like it everywhere else too” – Ousmane Sembène

Sembène won various awards at the Cannes, Berlin and Venice film festivals. As a writer, he published ten literary works, seven of which have been translated into English. Nearly each one of his films has been described as a ‘masterpiece’. But, most importantly, he inspired a continent of filmmakers and turned Africa from a consumer of films to a producer of them.

Seven decades after cinematography was invented, here was an African, filming African landscapes, filled with African stories in African languages. Samba Gadjigo, who directed the 2015 documentary Sembène! about his idol, claims that Sembène’s films made him realise that “as an African man, I had stories — beautiful, powerful, inspiring stories — that were mine, that were familiar, that celebrated my people. I didn’t need to look to Europe to find meaningful stories. Here they were.”

Not bad for a fisherman’s son who left school at 13.