Abdelfattah Kilito's 'The Tongue Of Adam' Is A Brilliant Indictment Of Chauvinism

Moroccan writer Abdelfattah Kilito, professor of classical Arabic literature in Rabat, seeks to answer the most fundamental question in an erudite and playful series of lectures entitled The Tongue of Adam, recently translated by Robyn Creswell.

To read The Tongue of Adam by Abdelfattah Kilito is to hurdle oneself deep into the folds of Biblical and Qur’anic analysis, medieval Islamic commentary, and literary theory. The book belongs at the very intersection of history, religion, and literature, and reconceives a foundational question of the Abrahamic narrative tradition: Where did language come from?

The book is a series of lectures, structured so that each chapter presents a handful of arguments and derivations centred on a general topic. Kilito moves from analyzing the paradisiacal origins of language in the Bible and Qur’an, to deconstructing various Tower of Babel stories and notions regarding multilingualism, before spending the rest of the lectures on the implications of the elegy of Adam: a premodern, maybe even ancient, poem attributed to the first man.

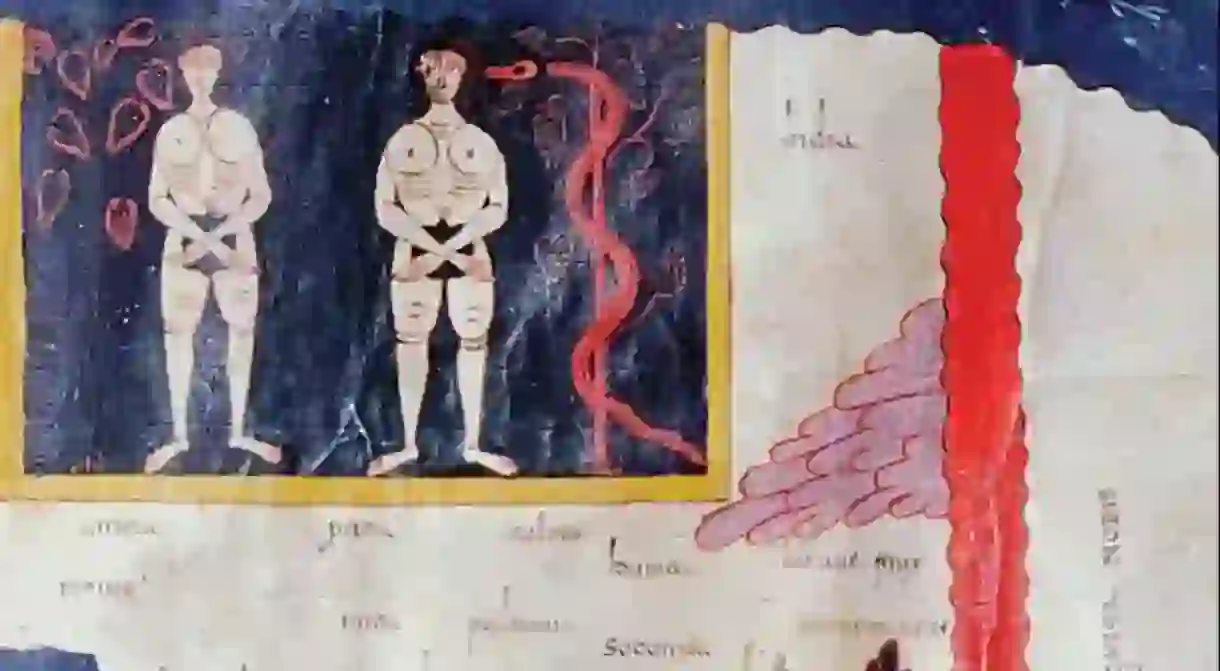

Naturally, Kilito begins right after the moment of creation in the Garden of Eden. His style of argumentation and analysis relies heavily on contrasting often directly opposing concepts. He regularly alternates between the physical and the emotional, the carnal and the divine, juxtaposing taste with knowledge, or speech with good and evil. Right at the beginning he draws an inspired parallel between the moment Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge, and the resulting punishment of the serpent; because it is called the Tree of Knowledge, and because eating its fruit teaches to distinguish between good and evil, it follows that to know is to distinguish, to separate, to parse. This separation occurs physically in the clefting of the serpent’s tongue, which further results in the serpent becoming a bilingual creature. This doubling at multiple levels of analysis pervades the book–the story of Adam’s tongue is fractured and bifurcated at each level. Kilito himself points out that as a symbol, the tongue itself is broken–does that refer to the organ or the idiom, the tool used to experience a physical sensation or the one used for speech?

A transition to the Qur’anic version of the garden story reveals the importance of commentators and interpreters of sacred texts. At no point does the serpent explicitly goad Adam and Eve into eating from the tree, but as Kilito notes, the “commentators wouldn’t be denied a chance to make the serpent play a role.” As a result, for centuries, Islamic narratives regarding the creation myth have featured a serpent, even though a serpent is never mentioned in the Qur’an. Interesting allusions and references allow for further interpretations. It’s as though new stories are birthed by older ones—by connecting the many allusions and references in them, Kilito gives interpretations that read like an Arabian Nights analysis of the Genesis creation narrative.

The chapters on the Tower of Babel, in which Kilito explores the theological and historical bases of multiple languages, are particularly noteworthy. He contrasts the Biblical story of Babel, from its inception to its conclusion, with the story of Babel as it was teased from Qur’anic verses by medieval Muslim thinkers. The emphasis in both stories is on the consequences of man’s ill-fated (though some would argue necessarily fated) challenge of God by building a tower to the heavens. Kilito’s vision again bifurcates, as the punishment faced by humanity is once more twofold: the destruction of the tower and the confusion of tongues–the onset of a multilingual haze. He then contrasts this narrative with another, drawing a new interpretation from the Babel story. Quoting the thirteenth century lexicographer Ibn Manzur, Kilito reveals and underscores God’s intent and desire to “make distinct the tongues of man.” God doesn’t punish man with multilingualism in response to some perceived Olympian-like insurrection. In the same way that knowing implies the ability to parse and distinguish–to separate–the very act of creation is an act of separation, as he writes, “the heavens are parted, the Earth is divided from the heavens, and men must also be distinguished from one another by their colors and tongues.” Referencing a Qur’anic verse which states, “We sent no messenger except with the language of his people, that he may enlighten them,” he concludes all languages are necessarily equal to God. From there he argues (through framing the argument using the views of another medieval scholar, Ibn Jinni) that Adam did not speak a singular, divine language which God fragmented following the destruction of the tower. Instead Adam spoke all languages, a beautiful multiplicative inversion of the Biblical story’s unicity. In the beginning then, man understood all languages, and it was only after, when ethnic and territorial divisions grew and ideologies calcified, that humanity began to speak only one language per people, slipping away from multilingualism. The result is not unlike that which followed Babel’s fall: a confusion of tongues.

From such wide and all-encompassing universal themes and stories, Kilito delves into some of the most esoteric Arabic histories and mythologies, centering the final three chapters on a mysterious poem attributed by some premodern thinkers to Adam himself. From this initial point, Kilito yet again embarks on a fractal journey, questioning the difference between poetry and prophecy in Arab folklore and meditating on the identity of the first mythological Arabic speaker, a man named Ya’rub. The self-similar analysis holds and applies throughout: a deconstruction of the ‘first poem’ composed by Adam falls into an analysis of the difference between poetry and prose in Arabic, which is in turn rooted in a distinction drawn by medieval Arab commentators between Arabic and other languages (with the former being the only language which can produce poetry, all others capable only of prose).

It is only appropriate that quotes on the verso would draw comparisons between the magical, mathematical Borges and Kilito. But beyond that, The Tongue of Adam is a quiet intellectual indictment of racial, ethnic, and national chauvinism, a text which derives an egalitarian beginning to language from the oldest of religious traditions. A brilliant and necessary book.

THE TONGUE OF ADAM

by Abdelfattah Kilito, trans. Robyn Creswell

New Directions

128 pp.| $13.95