Cairo: Reading the Revolution in Literature and Architecture

The struggle between the State and revolutionaries has not been resolved since the revolution started in 2011. The struggle resulted in different narratives that competed with each other on a space to prevail. The narrative of the State is reflected in architecture, in memorial building, while revolution is preserved in literature. This article aims to read the conflicting narratives, which are producing an overall discourse of the city in this critical moment.

The History

In order to be able to effectively read this article, it is crucial to be familiar with the developments of the Egyptian revolution. This link provides a brief presentation of the revolution timeline.

The Narrative

Poetry shadowed the revolution from the very beginning. On the eve of the 28th of January 2011, the Palestinian-Egyptian poet Tamim Al-Barghouti broadcast his poem to the Egyptians from Washington. The title of the poem is Ya Masr Hanet which is roughly translated to “Oh Egypt, it’s close”. The poem was so significant to the people in Tahrir that they managed to broadcast it on two big screens every couple of hours. The first stanza of the poem says:

Oh Egypt, it’s close

Batons are the remaining weapon for power to use

If you don’t believe it, come to the square and gaze

A king only exists in the imagination of his people

Whoever stays at home will be their traitor

From January to April 2011, Tamim worked on his epic colloquial poem Ya Sha’b Masr/ (Oh people of Egypt). As the title of the poem proposes, Tamim directs a lengthy speech to Egyptians to say that the revolution did not end; on the contrary, it has just started.

Following the timeline of the revolution, and according to the estimates of Amnesty International, the number of people killed in 2011 under Mubarak and the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) was 963, not to mention the thousands injured. Until today, not a single official has been held responsible for those crimes. In the first anniversary of the revolution, Qabila TV produced a video for Tamim’s poem, in which he recited verses from Ya Sha’b Masr accompanied by music and inserts from the year’s major events. The effect was tremendous, and thousands of people fled into the streets of Cairo the next day protesting against the military rule.

Mostafa Ibrahim is another Egyptian poet who grasped the moment of SCAF rule in Egypt in his poem “Today, I saw”. The poem employs the historical story of Al-Hussien, and draws the analogy between Al-Hussien destiny and that of the revolutionaries. Al-Hussien, the grandson of prophet Mohamed, fought for his people against the unjust rule of Yazid, and was betrayed by his people, and beheaded by Yazid’s army. Khaled Fahmy translated the last part of Ibrahim’s poem to English, in which he says:

Today, I saw the picture from outside

And said, even now, Al-Hussein will die again.

Today, I saw what the revolutionary sees

Al-Hussein’s body trampled by soldiers’ feet,

Jabbed by soldiers’ clubs.

People standing about weeping,

Instead of fending them off.

The flag is a sieve of bullet holes, shredded by bayonets.

The road draped in blood.

Today, I saw blood on the soldiers’ holsters

And knew that Al-Hussein is us all,

And the more they kill him, the more he lives.

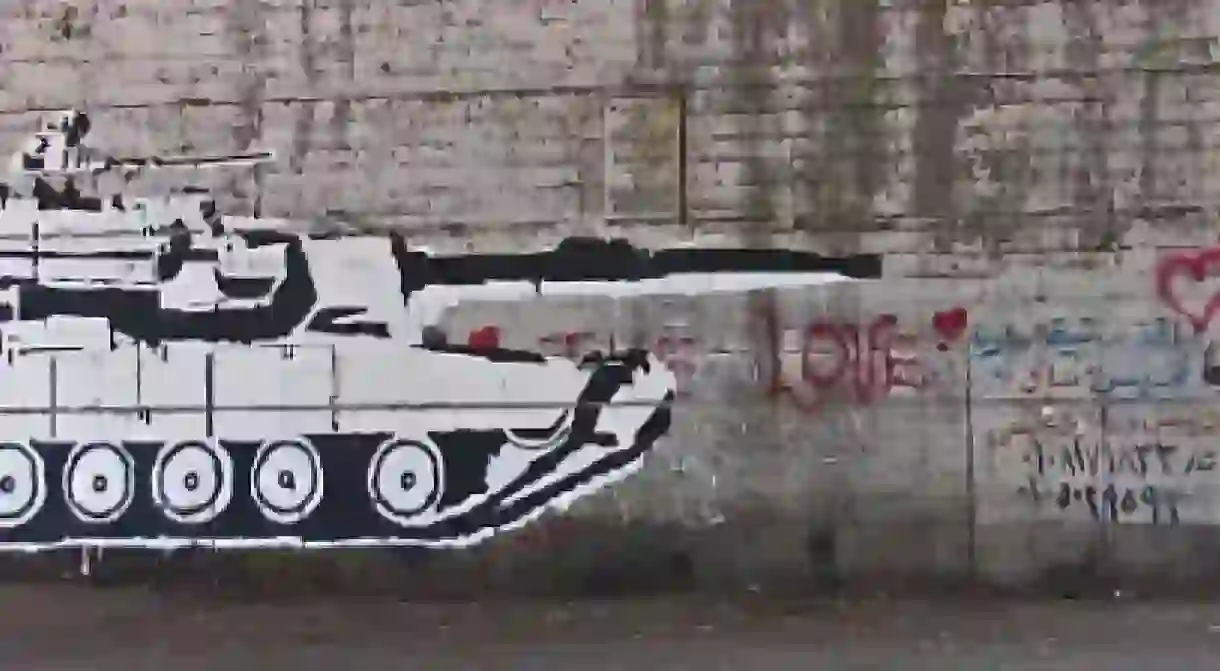

During the violent clashes, whenever a martyr fell, his compatriots would mark the path of his blood on the ground by stones. The memories of the revolution are far denser than any government could withstand. In the past four years, memories of the revolution were concealed by whoever held the power, and the sites of battles were continuously renovated to tell different stories with different priorities.

Mark Rakatansky, an assistant professor of architecture at Parsons School for design, defines architecture as ‘the management of what can and cannot be concealed’. He adds ‘it is because all that is supposed to be concealed refuses to remain concealed, that it must be managed through the constant presentation of certain conventions of architectural order and propriety’.

One of the architectural conventions that was added to Tahrir was the memorial the government dedicated to the revolution martyrs of both January 2011 and June 2013. This year, in the fourth anniversary of the revolution, the memorial was replaced by a giant flag pole that was installed in Tahrir on the third of February, just 9 days after Shaimaa Al-Sabagh was killed by the security forces a few meters from the square.

Forty kilometers east to Tahrir, Marshal Tantawy mosque stands on the way to New Cairo. The magnificent mosque is part of a huge construction project carried out by the army in the entrance of the new city. The first phase of the project included inaugurating a new axis that was named after the Marshal in November 2012. This date coincides with the first anniversary of the Mohamed Mahmoud events, during which 50 people were killed. The country at that time was ruled by the SCAF, which was led by the very same Marshal.

The German philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer explains that the meaning of architecture is ‘a function of its place in the world’ in a precise historical moment. In October 2013, the memorial of Rabaa square was inaugurated. In the heart of the memorial is a sphere that is embraced by two arms. According to the Engineering Authority of Armed Forces, the longer arm symbolizes the army, the shorter one represents the police, and the sphere stands for the Egyptians.

The memorial faces Rabaa mosque, which was the centre of the sit-in organized by supporters of the ousted president Mohamed Morsi. The sit-in lasted for 48 days before it was dispersed by the army and the police on August 14th 2013. According to Amnesty International, 1000 people were killed on the day of dispersal. The mosque itself was burned that day, and renovated by the army later on, but it hasn’t been open for prayers since then. The inauguration of the memorial coincided with October festivities which mark the army’s triumph over Israel in the 1973 war. The victory over the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in 2013 was marketed by the State as a victory over a national enemy. In such a polarized context, any opposing view to Rabaa massacre was silenced, condemned and convicted.

This moment was beautifully grasped by Mahmoud Ezzat who wrote the ‘Prayer of Fear‘. The poem was produced by Mosireen in September 2013. The poem, translated into English, reflects the hesitance, fear and deep grief of the revolutionaries who are against the rule of both the military and the MB, and who are definitely against killing people of any political affiliation.

Everyday millions of city dwellers are exposed to the narrative of architecture, while only few search for the counter narratives in literature. The streets of Cairo are loaded with a million silent stories, and the language of the city is only legible for those capable of decoding its silence and noise.