The Architecture of Functional Artistry In Henri Labrouste's Designs

Henri Labrouste (1801-1875) has long been recognised as one of the most important architects of 19th century France. As one who combined rationalism, light, and classical influences to form his own architectural language, it is not surprising that Labrouste’s work has often been a source of controversy and debate. Celebrated in 2013 through collaborative exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, it is clear that Labrouste’s work and influence remain relevant today.

Did you know – Culture Trip now does bookable, small-group trips? Pick from authentic, immersive Epic Trips, compact and action-packed Mini Trips and sparkling, expansive Sailing Trips.

Pierre-François-Henri Labrouste was born in Paris in 1801, one of four sons born to lawyer François-Marie Labrouste. At the age of eight, Labrouste joined the reputable Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris, before being admitted into the second class of the École Royale des Beaux-Arts in 1819. A member of the Lebas-Vaudoyer workshop, his notable talent soon became evident and he was promoted to the first class in 1820. He began competing for the Grand Prix de Rome the following year, and was unsuccessful in his first attempt, taking second place. However, after winning a departmental prize in 1823, he was given the opportunity to act as sous-inspecteur alongside Étienne-Hippolyte Godde, and subsequently went on to win the Grand Prix de Rome itself in 1824 with his design for a Court of Appeals building.

As a consequence of this success, Labrouste was awarded a place at the Villa Medici in Rome to study Roman construction for five years (1825-1830). There he encountered the functionalist theories of Jean Nicolas Louis Durand, and of course, the classical Italian structures which would later influence his most famous designs. His time in Rome would also lead to the controversy with which he is often associated; one year before his return to Paris Labrouste produced a restoration study of the temples at Paestum, and it was this highly contentious work which sparked opposition between Labrouste and the traditionalists at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Half a century later, the impact of the Paestum drawings upon academic dogma was still recognised. Their almost revolutionary significance was solidified through publication in 1877, the Gothic revival architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc describing the study as ‘quite simply a revolution on a few elephant folio sheets of paper.’

Even a century later the importance of this study, not only with regards to Labrouste’s career but also in terms of architectural innovation as a whole, has not been forgotten. In 1978, after visiting the Museum of Modern Art’s Beaux-Arts exhibition, which featured the drawings themselves, Peter Smithson told an audience at the Architectural Association in London, ‘[T]he rendered shadow of the feathers of the arrows and the shadows of the shields lashed to the columns are drawn so lightly that it’s almost impossible to believe it was done by human hand. It’s the best rendered drawing I’ve ever seen. In one long touch of the two hair sable brush the drawing reveals two languages at work: the language of the permanent fabric and the language of its attachments – that which continues the idea of architecture and that which is the responsibility of those who use it.’

Returning to Paris the next year, Labrouste moved away from the Romantic school which dominated architectural thought in the 1830s, instead running his own workshop and instructing students in the use of new materials, the vital pre-eminence of a building’s function, and in the art of combining minimalism with an appreciation for classical ornament. When his studio closed in 1856, the Encyclopédie d’architecture celebrated Labrouste’s work as a teacher and leader, summarising his philosophy as ‘the idea that in the design of buildings form should also be suitable and subordinated to function and that decoration should be born of construction expressed with artistry.’

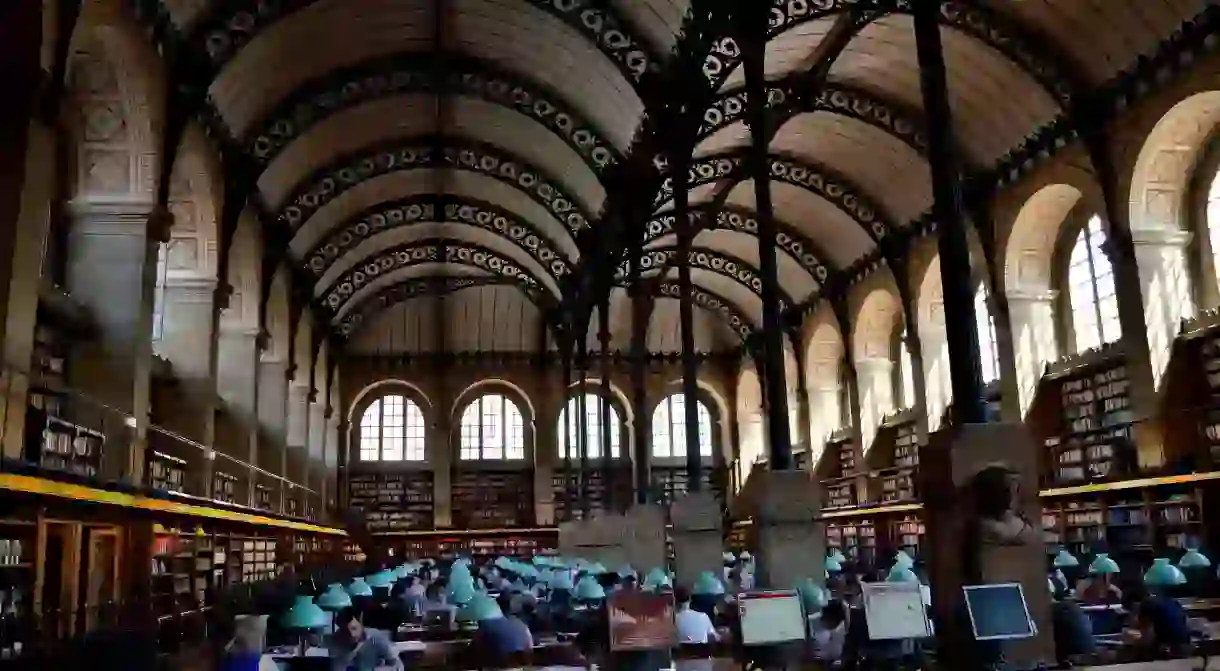

During his career, Labrouste took part in the design of many constructions and buildings, from hotels to tombs and monuments. However it is undoubtedly for his two spectacular reading rooms in Paris that Labrouste is most often recognised, namely the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève and what is now known as the Salle Labrouste in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (in the Rue de Richelieu). The innovations of these constructions exist in Labrouste’s use of iron, an industrial material whose potential for both elegance and functionality is exemplified in these libraries.

Commissioned to Labrouste in 1839, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève was the architect’s first major project, and a chance for him to demonstrate the validity of his design principles in the face of opposition. The large, oblong exterior of the library was in itself unusual at the time, whilst its appearance is suggestive of a similarly utilitarian use of iron inside the building. Compared with the austere grandeur of the exterior, the interior is, however, surprisingly delicate, characterised by its lightness and simplicity. Sixteen iron columns running down the centre of the room divide this vast interior into two barrel-vaulted naves punctuated by intricate metal arches, yet attention remains on the room’s primary purpose of learning and study. Remaining focused upon creating an intellectual and stimulating atmosphere, Labrouste also incorporated gas lighting into the building, and was one of the first architects to do so. Through such innovations, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève seems to embody Labrouste’s belief that functionality, when built with artistry, is the most expressive and beneficial form of decoration.

After continuing to develop his style over the next few years, Labrouste was employed to extend the Bibliothèque Nationale de France through the addition of a main reading room and a space for stacks. This reading room designed by Labrouste has since become the defining image of the library, and bears the name of the architect himself. Once again using the iron structures for which he is now known, Labrouste positioned 16 iron columns, each only one foot in diameter, at intervals throughout the room to create expansive 10-metre-high spaces. Natural ‘zenithal’ lighting filters between these columns as they support nine shallow domes, each with its own oculus; the neutral shades and subtle decoration of these domes contribute to the tranquillity of the room, providing readers and thinkers with the ideal environment in which to work.

Though he was adamant that no speeches should be made at his funeral, obituaries written around the world are a testament to the huge impact which he had upon modern architecture. His influence is recognised in innumerable styles, schools, and individual constructions, including Neoclassical forms, the Gothic Revival in France, the work of Louis Sullivan, ‘the father of skyscrapers’, in the United States, and even in the use of reinforced concrete. After his death, the Royal Institute of British Architects publically recognised his impact upon the art of architecture, ascribing to him ‘the vigour and vitality which has given birth to and guided the growth of the highly original art which marks the French school of the second quarter of this century.’

Since his death in 1875, the ramifications of Labrouste’s innovations in architecture have been repeatedly redefined, identifying him as an architect of truth, and as one who harnessed emptiness and light. Lucien Magne, author of L’Architecture française du siècle, the first history of modern and contemporary architecture, discussed Labrouste in terms of ‘art nouveau’ even as early as the 1830s, testifying to his singularity amongst the Romantic architects of his time. The book was published in 1889 to align with the Exposition Universelle, a fair which sought to demonstrate the modernity of France after the turmoil and Revolution of the last hundred years. The symbol of this modernity, and the entrance to the fair, was the Eiffel Tower, a huge construction formed using wrought and cast iron, a monumental structure in the ‘iron order’, of which Labrouste has been named the creator.

The significance of this French architect, therefore, has clearly not been forgotten. In 1902, a bust of Labrouste was placed in the Bibliothèque Nationale, and in 1953 the architect was commemorated again in the library’s first exhibition of his work. More recently, in 2013 the Bibliothèque Nationale collaborated with the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris to exhibit his work to a larger audience than ever before. The exhibition in New York contained over 200 pieces, from original drawings to modern films and models, and was the most-attended architecture show worldwide in 2013. The retrospective, Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, was the first solo exhibition of his work in the United States, and will surely not be the last.