NYC Artist Lawrence Weiner and the Art of Language

This article is part of our Explore Your World Through Language campaign.

Native New Yorker Lawrence Weiner, born in the Bronx, became a trailblazer for conceptual art in the 1960s. With the belief that a work need not always have a material or physical presence, Weiner was among the first to advance art as a language – his work consisting mainly of typography. For the past five decades, his works have been seen in obscure places all over the world. We take a closer look at the life and career of this conceptual New York City artist.

I’m trying to use language as a means of presenting a mise-en-scène, a physical reality.

—Lawrence Weiner in conversation with Willard Holmes, 1990.

Growing up in the Bronx in the 1940s and ’50s, Weiner’s idea of art was different from the middle-class perspective. Rather than fine artworks in formal exhibition spaces, he saw art on the walls of the city, which led to his fascination with public art with which passers-by could read and engage. Weiner came to the conclusion that the readership of a work was more important than its physical presence. With this belief that an idea alone could be a work of art, Weiner began using language as the primary vehicle for his work, challenging traditional ideas about the nature of art.

In 1968, Weiner wrote a declaration of intent:

“The artist may construct the piece.

The piece may be fabricated.

The piece need not be built.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.”

This manifesto was published in his first book, Statements, and shifted the responsibility of the work’s realization onto the viewer, transforming the traditional artist-viewer relationship. The book consisted only of verbal descriptions of sculptures’ materials and their relationships to space and structure. Weiner realized, after students cut down a sculpture that he made at Windham College in Vermont, that his pieces could be less obtrusive and that viewers could experience the same effect by reading a description of the work. This led him to the conclusion that a work could exist in the world without being physically constructed.

“I began to realise that if I could determine sculpture by the use of language it would allow itself to move from culture to culture,” said the sculptor in a video interview with Jesper Bundgaard for Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. “And the work has no metaphor and in having no metaphor it leaves it open for people to use the work to make a metaphor to suit their needs and their desires. It seemed to me an amenable way of placing my work in the world.”

Since his first book was published, Weiner has evolved from simply describing the materials and physical processes of works to taking fragments of conversations and poems to create his sculptures. Since his works exist only as words, they can take on many different manifestations, can be displayed in multiple ways and in every language.

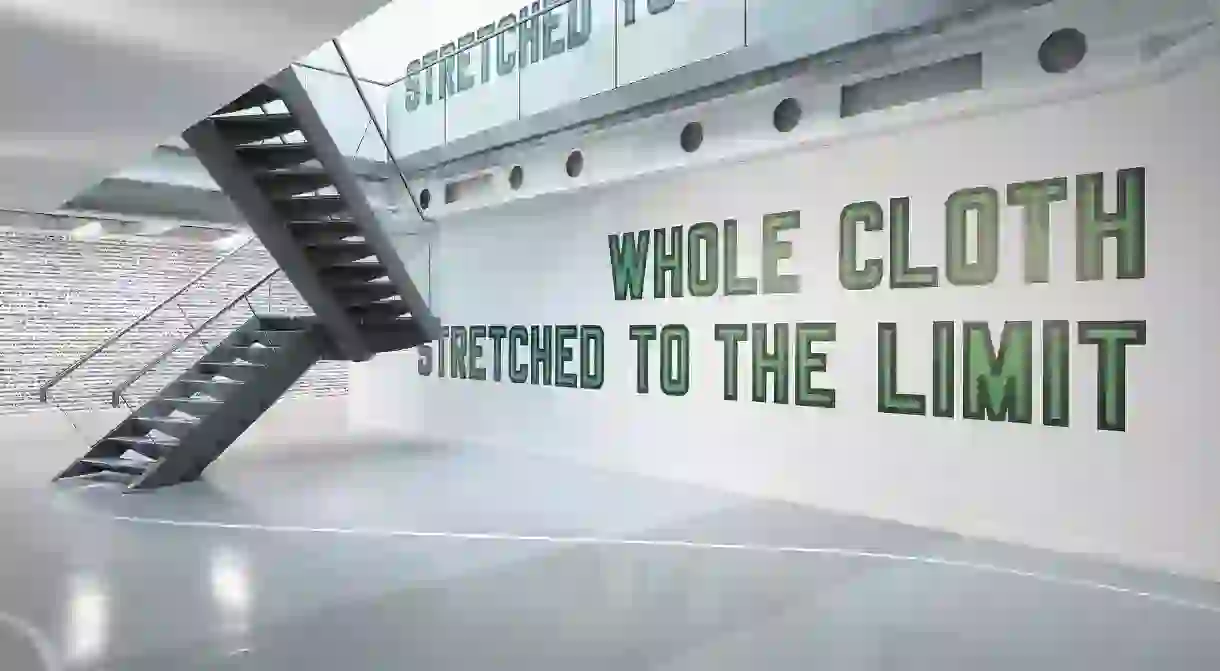

He’s sited his work on walls, windows, floors, and manhole covers of public spaces; as audio, video recordings and as printed books; as posters, graffiti and even tattoos. The poetic nature of his work sparks a conversation with the viewers and is able to resonate in a way traditional art forms cannot.

Wanting to use a non-dictatorial typeface, Weiner designed his own font, Margaret Seaworthy Gothic, which has a minimalist aesthetic. He experiments with the detailing of the type size, the surface texture, and the placement of letters, which can be stenciled, painted or mounted onto any surface; placement and color all vary depending upon the location of the work.

Weiner has fabricated several of his works, including one titled ONE QUART EXTERIOR GREEN INDUSTRIAL ENAMEL THROWN ON A BRICK WALL (1968). Referencing the style of Jackson Pollock, Weiner threw paint against the facade of his home, taking Pollock’s idea out of the studio and into the real world.

Art is still about the communication of one human being’s observations to another human being with the intent of bringing about a change of state.

—Lawrence Weiner

Unlike other artists such as Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, who have used language as a form of communication or call to arms, Weiner has, for the past five decades, created thousands of linguistic works that encourage multiple interpretations and pose a question to make you consider the “what if?”.

With solo exhibitions in cities including Amsterdam, London, Barcelona, Munich, Bordeaux, Cologne, and Mexico City, his conceptual thinking has now reached countries all over the globe. In 2007, the Whitney Museum of American Art held the first major US retrospective of his work, and although suffering from ill health, the New York-based artist continues to work with a solo show scheduled at Taro Nasu Gallery, Tokyo, in 2018.

This article is part of our Explore Your World Through Language campaign. If you enjoyed this exploration of the wonders of words, why not sink your teeth into these great pieces:

These Silent Signals Don’t Always Mean What You Think