In the West Village, Llama San Celebrates Nikkei Cuisine

Nikkei cuisine – the coalescence of Japanese and Peruvian influences – has long been tricky to find outside of Peru. Llama San, a new restaurant in Manhattan’s West Village, is looking to make it more accessible by introducing this fusion cuisine to New Yorkers.

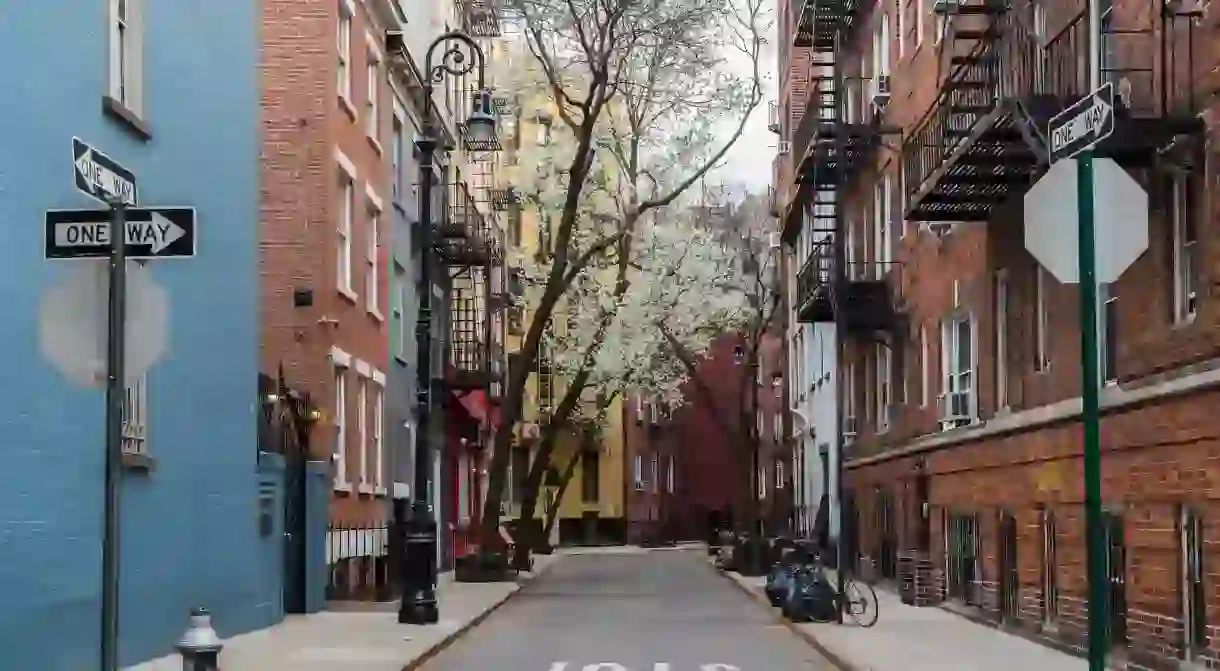

For chef Erik Ramirez, opening his newest restaurant, Llama San, was certainly fortuitous. Ramirez, who’s at the helm of two Peruvian restaurants in NYC (Llama Inn and Llamita), and his business partner Juan Correa had only just swung open the doors of Llamita – the team’s sandwich shop – when their broker informed them of an available spot. It was right around the corner in the West Village, and it wasn’t even on the market yet.

“It took us four years to open Llamita, so we wanted to wait a little [to open another restaurant],” Ramirez says. “But this opportunity was thrown in our laps.”

Plus, Ramirez and his team had long been discussing the move to open a Nikkei restaurant, and this seemed like the perfect opportunity. Llama San is the embodiment of Nikkei: the fusion of Japanese and Peruvian ingredients and techniques.

Thanks to an influx of Japanese immigrants who moved to Peru in the late-19th century, the landscape of the country drastically changed. At the time, Peru was the sole South American country that had diplomatic relations with Japan, whose economy was at its worst. To help the struggling nation, Peru created work contracts for Japanese people, stipulating they could come to Peru for a few years and then return to Japan. Many ultimately settled down in Peru, and this blending of cultures resulted in its own kind of cuisine – one not often found outside of Peru.

“I believe that the food lasted and became what it is now because the Japanese people stayed in Peru and built families and created businesses, fusing with Peruvian people,” Ramirez says.

But Nikkei was hardly born overnight. The first Japanese immigrants who docked in Peru simply tried to cook their own food – only using whatever ingredients were available to them at that time.

“That wasn’t necessarily Nikkei,” Ramiez says of this first wave of cooking. “The second wave was when it became Nikkei. The Japanese parents had their kids [who] grew up with those Peruvian flavors and also grew up eating Japanese food because of their parents, and they learned to fuse those two.”

Ramirez, who is a first-generation Peruvian-American, was raised in New Jersey, but his familiarity with Nikkei cuisine is thanks to his grandmother, who is Nikkei (her mother is Peruvian, and her father migrated from Japan to Peru). Although Ramirez grew up eating Peruvian and American food, his close ties to Nikkei inspired him to dedicate a restaurant entirely to the craft.

“I think one of the best ways to learn about culture is through food,” Ramirez says. “I can learn more about where my grandmother came from.”

At Llama San, the food is a manifestation of that blending: an ode to Peru, Japan, Nikkei and New York City. Ramirez’s riff on tonkatsu is perhaps the best example of this amalgamation of cultures. He crisps up pork like one would a milanese – breaded, pounded and fried – and crowns it upon a tangle of udon noodles, slick with tangy, green pesto. The dish plays on tallarines verdes con apanado (meat swirled with pesto spaghetti), a Peruvian dish Ramirez grew up eating. “It really shows the modern Japanese-Peruvian mix,” Ramirez says.

The rest of the menu is rounded out with a slew of dishes dedicated to this unification. Scallop ceviche, splayed out in small mounds, is peppered with chirimoya, avocado and sesame. Soft hunks of Japanese eggplant are brightened by green herbs, fresh cheese, grapes and pine nuts. A fistful of translucent, crispy rice noodles hides a pile of mushrooms and seaweed dusted with togarashi.

“Nikkei is what New Yorkers like to eat,” Ramirez says. “They love their Japanese cuisine and their Latin-style food.”

Japanese and Peruvian ingredients equally inspire the beverage program. Guests will find the likes of fusion cocktails, including La Mala Muerte (Singani, bitter Bianco, nori, sake and vermouth) and Harajuku is Dead (milk punch, Japanese gin, butterfly pea and verjus). “We make really popular classics and twist them to our Nikkei style,” head bartender Natasha Bermudez explains. “Our most popular drink right now is our old fashioned; we use a Japanese whisky that we infuse with roasted cacao.”

Ramirez hopes that Llama San will be a catalyst for the rise of Nikkei and Peruvian cuisine in New York. While there are already a few Nikkei restaurants scattered throughout the city, the cuisine isn’t as ubiquitous as, say, Chinese and Mexican fare.

“A lot of people don’t know about Peruvian food; they think it’s just rotisserie chicken, green sauce and ceviche,” Ramirez says. “[Llama San] is showing that Peruvian cuisine is more than that. People start saying, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t know there was a cuisine called Nikkei that was Japanese and Peruvian.’ It’s pushing the culture and cuisine forward, making it more popular. That’s the goal.”