How the Chicago River Was Reversed

Lake Michigan is one of Chicago’s biggest attractions, and it’s all thanks to an ambitious feat of engineering that reversed the flow of the Chicago River.

Unsurprisingly, given its location, Chicago’s main water supply has always been Lake Michigan. However, in the second half of the 19th century, as the city enjoyed an industrial boom, the river was frequently mistreated. Waste and sewage would drain into the lake, and the drinking water for the city became polluted, leading to outbreaks of typhoid and other waterborne diseases. A persistent urban myth states that a particularly disastrous storm in 1885 washed waste from the sewage system into the drinking water inlets, causing an epidemic that killed approximately 12 percent of Chicagoans at the time. While no such singular disaster was officially recorded, the Sanitary District of Chicago was formed four years later to tackle the city’s sanitation problems.

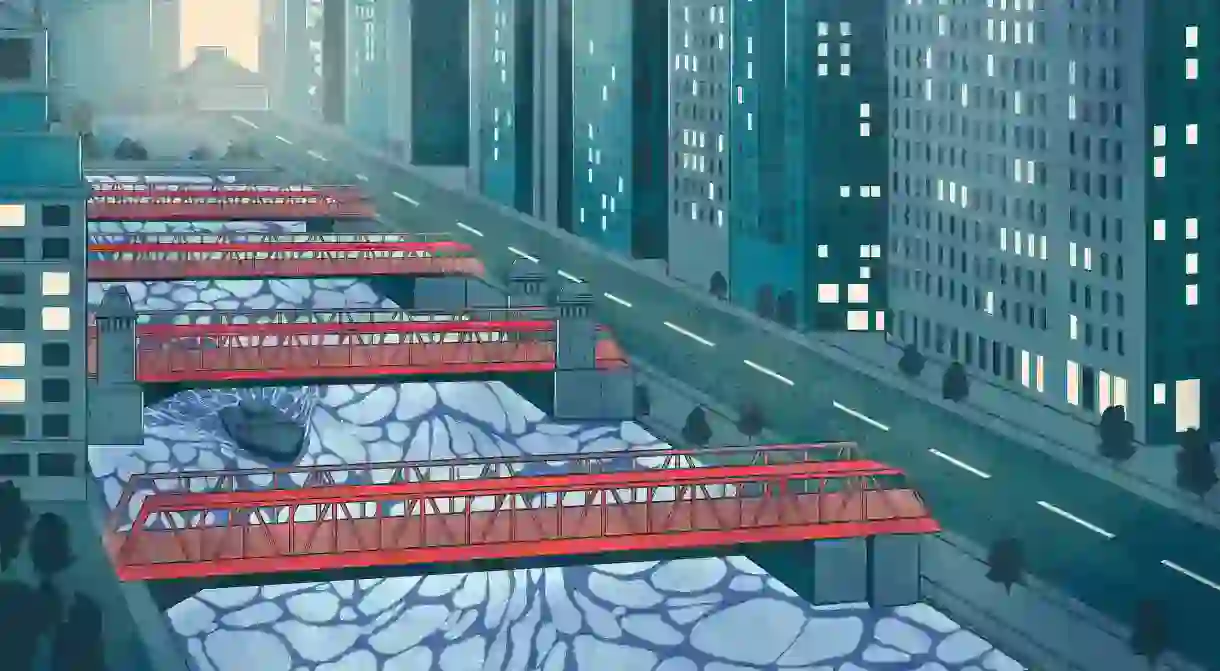

The idea to reverse the flow of the river away from the lake had already been unintentionally attempted in 1871 when the existing Illinois and Michigan Canal was deepened, unexpectedly pulling in water from the Chicago River. Although the effects were only temporary, it planted the seed of a solution. In order to achieve a permanent reversal, the city began constructing a new canal to join the Chicago River with the Des Plaines River, which would flow into the Illinois River and eventually join the Mississippi. This idea would also benefit the city by providing a continuous transportation link from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

While the idea was relatively simple – using gravity to make water flow from the river into the continually deepening canal and then into another river – the construction was not. Beginning in 1892, the main channel (the first phase) of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal took eight years to complete, and nearly 40 million cubic yards of earth and rock were removed all along the 28-mile (45-kilometer) stretch. The project required new innovative techniques, establishing what became known as the “Chicago school of earth moving,” also used in the 1914 construction of the Panama Canal. By 1900, the first phase of the canal opened, with the river permanently reversed and the waste problem solved.

Although the system would eventually be named a “Civil Engineering Monument of the Millennium” by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), not everyone considered it a triumph. Missouri objected, fearing that all of Chicago’s pollution would inevitably flow into the Mississippi – the source of St Louis’s drinking water. In 1906, the state of Missouri sued Illinois, but the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of Illinois, stating that there was no evidence that the water quality in the Mississippi River had been affected.

Construction continued uninterrupted, and the canal was extended several times, including the building of other canals to support and perfect the system. With the reversal of the river, the water supply greatly improved, along with Chicagoans’ health. This piece of Chicago’s history was a groundbreaking achievement in more ways than one.

Esme Benjamin contributed additional reporting to this article.