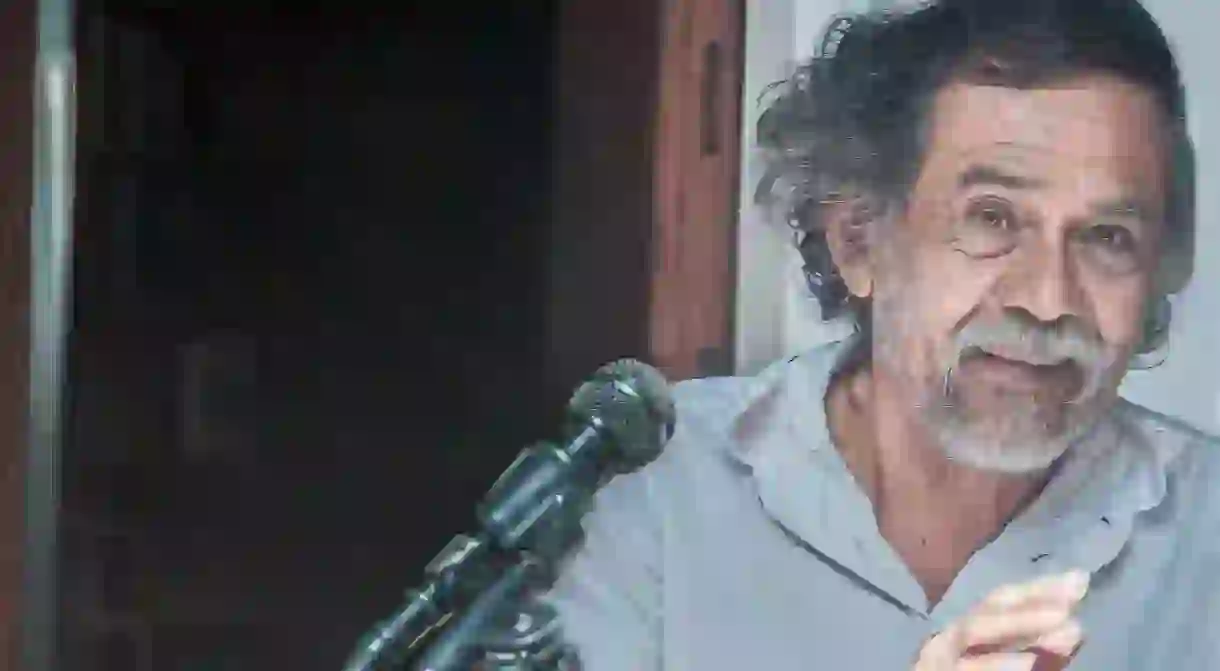

Francisco Toledo's Legacy in Oaxaca

As a hugely respected artist around the world, Francisco Toledo has had a lasting impact on the city of Oaxaca. Here’s how to learn more about one of Mexico’s greatest artists.

In Mexico, you know you’ve bumped into someone important if people in the streets call him or her, ‘maestro’ or ‘maestra’ – in this instance, not as in ‘master’, but as in ‘teacher’. The more people call someone ‘teacher’, the more lives they have influenced. Well, everyone in the streets of Oaxaca called Francisco Toledo ‘maestro’.

Francisco Toledo had his first exhibition at the age of 18 having had no formal artistic training other than a few after-school art classes in the city of Oaxaca. So it was a combination of raw natural talent and chance that his drawings were discovered by a friend of gallery owner Antonio Souza in Mexico City. Souza was already well-known for promoting the Breakaway Generation that included artists like Leonora Carrington, Manuel Felguérez, Lilia Carrillo, Juan Soriano and Rufino Tamayo.

Toledo’s first two exhibitions in Mexico and Texas with Antonio de Souza were successful enough to earn him money to go to Paris, where he was mentored by Rufino Tamayo and guided by Octavio Paz who introduced him to his intellectual circle. There, he was able to see the work of the artists he admired: Jean Dubuffet, Francisco de Goya, Jean Miró and Paul Klee. But Toledo was equally attracted and impressed by the works of aboriginal art he found at the Musée de l’Homme. Their universality and profoundness were relatable to him in terms of his own characteristic Zapotec imagery, inhabited by the mythical creatures of the stories he was told as a child by his grandfather.

Francisco Toledo went to Europe to perfect his training and broaden his artistic knowledge, then returned to Oaxaca with a stronger appreciation and commitment to the richness of his own culture and pride in his indigenous roots, which he defended until he died. As an artist, he mastered diverse techniques and materials but was most prolific as an engraver. Toledo was, as ethnographer Joaquín Galarza described, “The only painter with heritage of tlacuilo”, after the Náhuatl word for naming the wise graphic artists who were responsible of documenting pre-Hispanic culture and thinking.

Toledo’s legacy goes beyond his artistic accomplishments. He understood art. Not only as an expression, but also as powerful enabler of social transformation. Here are some of the cultural institutions created or influenced by the Mexican artist.

Where to go

The multidisciplinary space Casa de la Cultura de Juchitán was created along with poet Elisa Ramírez in 1972. Toledo wanted all disciplines of art to be available to the people in the Istmo de Tehuantepec area, and in 1988, that idea extended to the city of Oaxaca where he founded IAGO, the Graphic Arts Institute of Oaxaca. The place was set up at a centrally located (in front of the Santo Domingo Convent) colonial house that the Toledo family donated to the Institute of Fine Arts of the State of Oaxaca. The space houses a library of over 60,000 volumes, a graphic art collection (one of the most relevant of its kind in Latin America) of around 40,000 pieces, and three exhibition galleries. In 1996, a very important addition was made: the Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo, which consists of three main collections: the first is a series of images by Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo, given by himself in life to Toledo as gifts or in exchange for artwork, the second is a collection of images by Henri Cartier-Bresson that Toledo acquired, and the third one is a collection of images by photographer Graciela Iturbide that the artist personally donated to the institution.

In 2004, Toledo acquired an old textile factory in the town of San Agustín Etla, 20 minutes away from the city of Oaxaca. There, with the support of the Mexican Ministry of Culture and private funds, he installed the Centro de las Artes de San Agustín Etla (CaSa), an ecological arts center which works as a space for artists of diverse disciplines and backgrounds.

Francisco Toledo was also an influential figure in the creation of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca (MACO), founded when a group of artists returning to Oaxaca after training abroad raised the need for a space to establish a link between local artists and the global contemporary art community. The artists relied on Toledo to be their representative before the government for the procurement of the project, and in 1992 MACO was inaugurated.

Francisco Toledo also worked alongside fellow Oaxacan artist Luis Zárate to turn the threatened back patio of the Santo Domingo Ex-Convent into the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca. The space was once the orchard of Dominican friars, and now houses a plant sanctuary of around 10,000 species from all over the state of Oaxaca. Highlights include maize plants grown in Guilá Naquitz in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, the place were the world’s oldest corncobs to date have been found (almost 7,000 years old), a 5-ton barrel cactus and a 3,100 species-strong herbarium.

Francisco Toledo died from a two-year-long illness with pulmonary cancer in September of 2019. He complained in life that he didn’t work enough on his art because somehow he ended up involved in projects he didn’t always plan to. But people relied on him because they knew that once an important initiative fell in his hands, he would follow through. He was a natural leader and wanted to give back to younger generations of artists and creators. He mentioned in interviews how Rufino Tamayo used to tell him: “Stop doing all those things and put yourself to work, you’re a painter not a politician”.

“I should have listened to him…” Toledo agreed, “but no, there’s something that pulls me to the other side”.