A Space For Art: Nasser Al Yousif And The Origins Of Bahraini Art

Pioneering Bahraini artist Nasser Al Yousif was primarily responsible for developing the modern tradition of art in Bahrain, and for linking it to the traditional forms of representation in the country. As such he developed a space in which a Bahraini conception of art could emerge which, as Arie Amaya-Akkermans attests, allowed future practitioners to delimit their own space for Bahraini art.

Art history does not designate places or outline maps. What do you see in a map? Coastlines, water depths, or other information of use to navigators. They serve to create an optic illusion about the world: Space is built strictly along geometrical lines and from here we derive the notion that all space precedes us. ‘It has always been there’, one would be tempted to say. There was a time when art history mapped certain things of the world; species of spaces, trajectories, traces of physical places. These apparently linear sequences can be easily replaced with dots – moments in time that emerge sometimes simultaneously in different places, defying the traditional notion of geographical mapping.

The question of how space is really configured when we dwell in it isn’t only a metaphysical commodity, but rather, it provides a framework for art and history to occupy a room of their own. French writer Georges Perec asks the obvious: ‘What does it mean to live in a room? Is it to live in a place to take possession of it? What does possession of a place mean?’ And perhaps the answers are not necessarily satisfactory.

For Perec, acquiring or appropriating space is a form of knowledge, a making sense of the world, and one could say also, bridging the gap of the Kantian distinction between knowing the world and having a world. Space appears and manifests in its reality as our gaze travels through it and gives us the optical illusions of distance. In Perec,’The surprise and disappointment of travelling. The illusion of having overcome distance, of having erased time. To be far away.’ But he is also audaciously careful to note that, ‘My spaces are fragile: time is going to wear them away, to destroy them.’ The arresting sense of time that we derive from his proposition is a warning for the instability of geography.

When you travel to a country without an established art history that can map the contours of modernity, how does art help you to make sense of the world from that place? If you want to really absorb a place, to take it as a whole in one stare – in the same way one admires paintings, without ‘reading’ – and circumventing the illusion of historical knowledge, one needs to learn how to stare rather than simply seeing things ordered hierarchically and chronologically. Susan Sontag instructs: ‘A stare is perhaps as far from history, as close to eternity, as contemporary art can get.’ Eternity here is not identified with the unrestrained and total consciousness of God but with a distinction between memory and history. In the words of Pierre Nora, ‘memory as a perpetual actual phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present and history as a mere representation of the past.’

The Kingdom of Bahrain is one of those fragile places where the historical viewpoint only distorts visual possibilities: Even a brief contact with the land will show you the extent to which a map is only an enclosure rather than merely a physical boundary. Whatever is understood as memory in the visual culture of Bahrain is more often than not a strict framework of reference not to the singular ease with which tradition overlaps with lived moments but rather to the enormous burden of an abstract past that needs to be immortalized, memorialized and monumentalized. This dislocation of time finds its shape in the spatial topography of art as a fast-forwarding movement rather than as a self-reenacting remembered present.

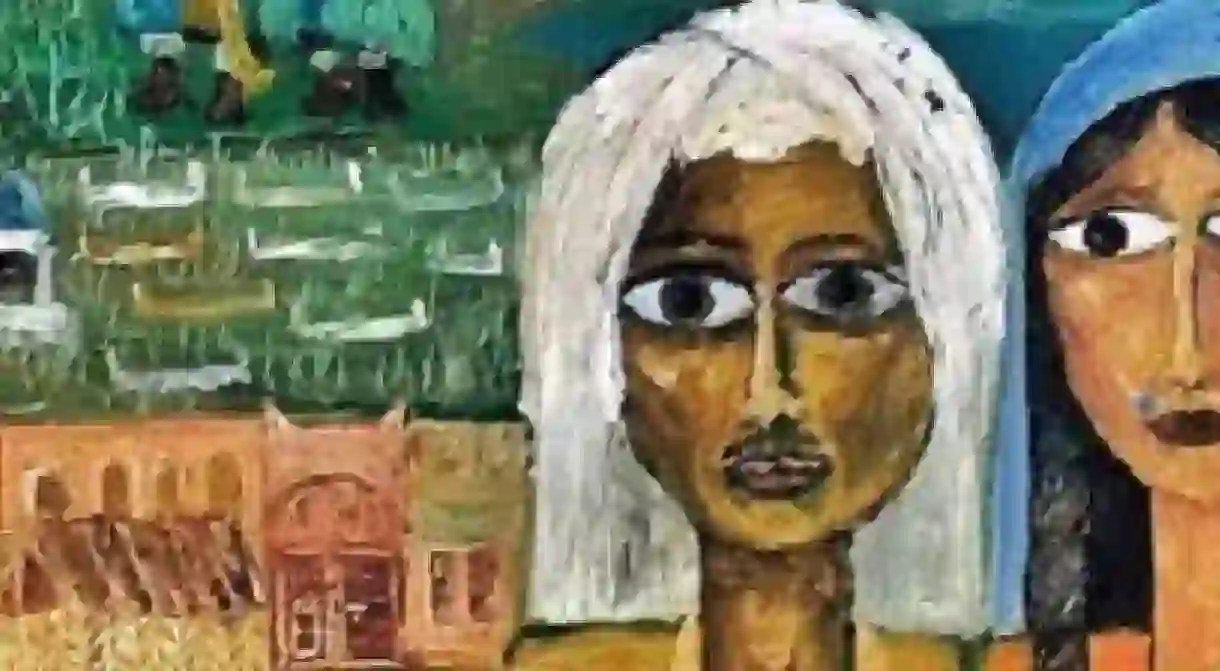

A singular exception to this practice is the work of early painter Nasser Al Yousif (1940-2006) who is to be counted among the pioneering figures in the art movement in Bahrain and in the Arabian Gulf. The Muharraq-native artist whom I discovered while researching the early beginnings of art movements in the Gulf region represents what is now absent from the visual culture of the Arabian Gulf and one of the explanations for the cultural crisis that plagues the identity of local artistic production, perhaps not in terms of galleries, collectors and exhibitions but in the making sense of local space (what is one’s own?) and appropriating it, to which Perec refers. Space in Bahrain remains not only an unstable notion but an unfinished patchwork in which different types of modernities, histories and counter-histories convene chaotically.

Todd Reisz speaks about space and public space when trying to visualize Bahrain: ‘Even while it has urbanized, Bahrain has consistently challenged the legitimacy of architecture. Its urban centres remain defiantly stretched out on plains of un-delineated space. Open space is not park or public space. Open space is vastness, non-distinction, void. Bahrain expresses a resistance to fill every void.’ Space is not an orientation or horizon of the gaze as much as an amorphous field of ungraspable geometric isonomy.

There’s an obvious question for the visitor to Bahrain: What is it that this island wants to tell us? One is looking for the story-teller. Could it be this building? Could it be that enclave of palms abandoned in a corner between traffic junctions? Could it be the reclaimed land? Is it the void? Walk from Juffair to Adliya on a warm day and interrogate the absent signs. The visual presence is overbearing, geometric and flat. All the lines are clean and clear. No symptoms of history, which is usually rough-edged, circular, humorous and frantic. But Nasser Al Yousif is one of such story-tellers. Words of caution are necessary. Sarah Kofman warns us that: ‘And so it is not the painting that speaks. A painting does not mean to say anything. Were speaking in fact its aim, it would certainly be inferior to speech and would need to be sublated by language to receive meaning at that. Between the figurative order of the painting and the discursive order of language there exists a gap that nothing can bridge.’ Being a story-teller here, as a painter, comes in two different forms; first there is the detective work, second there is the assembling of the signs.

The painter as a detective: Nasser Al Yousif has gone to the coastlines, to the water depths, and he has heard the soundscapes; he has seen what no one else remembers. He has seen the houses, joined to one another by threads of color and form, long before the void began to appear. And then there are the signs. He paints through epiphanies as Hélène Cixous has told us about Monet: ‘I would like to break your heart with the magnificent calm of a beach safe from man. But I can’t do it. I can only tell it. All I can do is tell the desire. But the painter can break your heart with the epiphany of a sea. There’s a recipe: ‘To really paint the sea, you have to see it every day at every hour and in the same place, to come to know the life in this location.’ That’s Monet. Monet who knows how to paint the sea, how to paint the sameness of the sea.’ What is it that the painter is seeing here every day and in the same place? He sees through concrete walls, finds a land sometimes ancestral and sometimes mythical; bathed in green and coated by the traces left in the air by a mirwas and a jahlah.

Even in his later years after he went blind, it was in his linoleum prints – in black and white, and the first of his works that I had the opportunity to see in Bahrain – that he depicted traditional life in the island in the way that music would do it, and to borrow an expression from Adorno, treating the meaningful content of orality and signifying language as if they were broken off parables.

But it was that painting that I eyed in Janabiyah, The Land of Peace, hanging from a rather rustic wall in the home of a collector, what opened my eyes to the Bahrain that I had always wanted to see. Taking a bird’s eye view from above, the neighbourhoods of an old Manama unfold in a convex nearness that reflects the nature of a society very closely knit together as if one could hear – from the painting – the interwoven stories that are now silenced in the formal principles of abstract art. The careful observer will notice that the houses are tied to one another in the form of a verse from the Surah Al-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Koran expressing the greatness of God and that plays an essential role in daily prayers, swirling out of the centre to form the community.

There’s little doubt that this is a Bahrain that few have had the privilege of seeing and it is not a matter of nostalgia over the loss of the traditional home for the more homogeneous living spaces of modernity, but rather, a radical openness towards what Pier Paolo Pasolini called, the scandalous and revolutionary force of the past. The past is in his paintings, a lived memory, as if it were something one can still hear, and not merely dead historical time but what is most absolutely present: The signs, the loud absent signs. One can almost hear the stories and the drums coming out of the painting in wholes. Historical paintings, just like historical novels, are no longer what we demand from art, now we demand more, in fact, we demand everything. As Cixous puts it: ‘I want to take hold of the third person of the present. For me, that is what painting is, the chance to take hold of the third person of the present, the present itself.’

And why would one travel thousands of kms to an island in the Gulf armed with no other navigation maps than some vague indications about its art history to hear the stories of Bahrain from a painting hanging on a rustic wall in a house in Janabiyah? To take hold of a present that is not a historical tense but something concrete: What is present, and what is present, never ends. Or, in the words of Perec, to remember that the earth is a form of writing, a geography of which we had forgotten that we ourselves are the authors.

By Arie Amaya-Akkermans