Artist Henry Hudson Discusses Inspiration and Plasticine

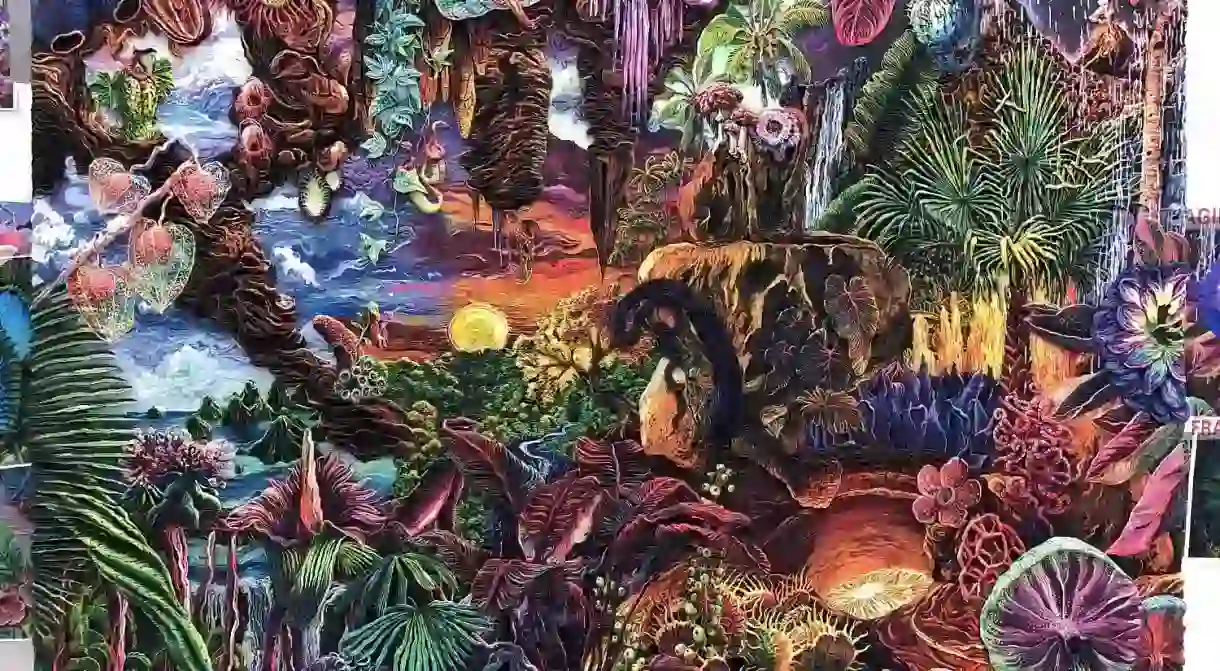

Walking into Henry Hudson’s East London studio feels like entering an Old Master’s workshop: it’s bustling with creative energy and filled with people heating up his homemade plasticine with hairdryers. Hudson took some time to talk to Culture Trip about his art and inspiration among his vividly coloured works.

Do you remember a moment when you thought ‘This is what I want to do in my life’?

My father is a sculptor and my brother is a ceramicist. When my father started sculpting, I was about 13 and his girlfriend at the time was a painter. They lived in Majorca and had big studios where they hosted collector dinners. In the day it was sunny, we went swimming and this painted in my head a very romantic idea of being an artist.

My grandmother was a Bletchley House code-breaker and also made scale model houses of predominantly Georgian buildings. They would often take a year or two to make, which is quite similar to how long it takes me to make a piece. My mother was a chef who worked for Marco Pierre White at Harvey’s, which was his first restaurant and had three [Michelin] stars. In my family life, I was surrounded by people who made things with their hands and who made their living from it.

There is always a comfort when you make a work, whether it’s sculpting or painting; you get lost in it and it becomes like a comfort blanket. My upbringing is definitely colourful: I was sent away to school very young, my parents are divorced, there were a lot of people coming in and out of my life. The consistency throughout was drawing and painting, and I was good at it—you know, from a craft point of view.

Where do you find inspiration?

When you are younger, you are more prone to think about that. As you become older and your life is your art and it’s 24 hours a day, there are moments and pockets of fresh air or clarity. But inspiration is not how it is depicted in films. There are no big eureka moments. They are very subtle and can’t be clearly pinpointed.

What is your process to get to a finished artwork?

An idea starts in the head and it might stay there for a while. I don’t know about other artists but I have sketchbooks. I will start with doodles, drawings and thoughts. It can sit around for a long time. Now I am bit more cautious, while before I would say ‘This is what I am going to do’ and execute it. Now I tend to sit on things for a bit longer. I recently made a lot of things and then ended up throwing them in the skip.

I am currently looking at the seven deadly sins and dystopian ideas of the future. They will be pen and ink watercolours, originally, and I will then turn them into tapestries digitally. I have been looking a lot at William Blake, Chris Ofili and Henry Moore’s work for these tapestries.

Your work seems to draw from past artists and movements. How do they inform your practice?

Any contemporary artist has to know a little bit about art history. It’s a language and you need to speak it. Past artists play a massive role but also present artists. There is always a flux and you are constantly looking at the past to build into the future. There are cornerstones in human beings: emotions, feelings, fear, anxiety, life, death and all these big themes drive art. Often it boils down to them.

What does a typical creative day look like?

I do a lot of self-care. I gave up drinking nine months ago. When you get older, time becomes more precious. I tend to work late and get up late. I am usually in bed by 1 am and get up at 9 am. I have breakfast and do a bit of work on the practicalities of being an artist like emails and shipping artworks. Normally, I am most productive for five hours a day. When I work I exert quite a lot of energy. Sometimes I don’t get down to the studio until 2 pm. I am currently working on some tapestries, so after 9 pm, I sit here and find images, I am watercolouring and drawing.

How did you end up using plasticine as a medium?

When I left St Martins a dealer said ‘You have a skill as a draughtsman, give me something to sell.’ I had £40 ($56 USD) in my pocket and I love impasto painting but I couldn’t afford the oil paint. I saw the plasticine in the kids’ section and I took it home. I mixed a red and a white and I got a pink. It happened out of accidental necessity.

I have been working in plasticine for a number of years. I just started adding paraffin wax to make it more elastic, which will allow me to use brushes and make the work a lot freer. It’s hard to explain to someone who is not touching it, but up to now the medium itself is dictating what to do so I want to change that and become more expressive. I’ve taken it from buying it to packets, to having machines and making my own colours. I run an old type Renaissance studio, I make colours there.

At the moment, I am experimenting a lot. Some might not make it. I am working with tapestries and in scagliola (imitation marble or other stone), an 18th-century medium. I’m also doing some woodbury type prints and have made some ceramics with my brother.

What is one thing you love and one thing you hate about the art world?

Intimacy for both. The reason for that is that intimacy is overriding all of it. I love it: the art world is a theatre and a club. For people who grew up like me who got badly bullied, or always felt like an outsider, it’s attractive. Here you can be weird, you can be wacky, and you can make a career out of it. I love the intimacy: the relationship between my art dealer and me, my collectors, the dinner parties, the artworks. As with any relationship there are the negative aspects of intimacy. There are people at the top, there are definitely superficialities within it and that can be annoying. Sometimes it feels like who you know not what you know.

Are there any insider secrets you wish you had been told before deciding to become an artist?

Firstly, art schools can do a bit more to give people a better understanding of the difficulties of being an artist. I think going to work for an artist is a really good idea. Some of the people that help me here are artists and work here part-time to subsidize their career. They are learning by being here. The other thing is finding the galleries and artists you like. Making sure you are there at private views. You can be the best artist in the world but no one will know who you are unless you show people. I think young artists need to be a bit more proactive about it, they need to be hungry for it.