LS Lowry: The Strange Beauty In Poverty And Gloom

20th-century British artist LS Lowry clutters his canvases with factory settings and frenzied figures in flattened scenes, capturing the particular energy of industrial England. The surrounding economic depression, violence inflicted by war and the resulting spread of illness provide unique inspiration for this painter of modern life.

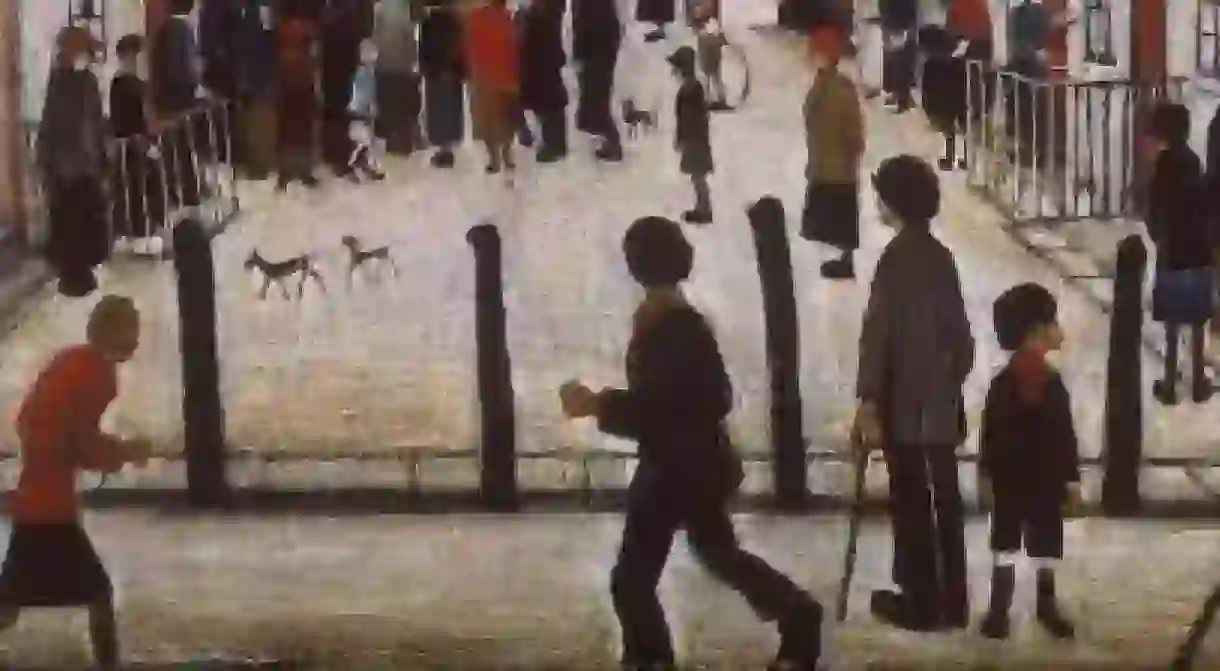

Stacked houses, factories, fairgrounds, football stadiums and blackened church facades crowd the shortened foregrounds of LS Lowry’s canvases. Rising chimneys pierce the air, emitting a steady flow of smog that fills these densely populated frames. Within fragmented cityscapes anonymous yet distinct figures, his so-called ‘matchstick men’, group together in communal purpose, engage in individual daily routine, or speed fourth in joint determination. For 40 years Lowry worked daily to capture the industrial fervor he witnessed in the urban landscape of Salford and Manchester. He recognised an unusual beauty and penetrative power in the economic strife, war-torn communities, or rampant spread of illness that formed his subjects.

Lowry did not work full time as an artist, but as a rent collector, returning home to paint every evening. His occupation thus gave him understanding of the dismal conditions and the honorable livelihood of tenants living in the slums. Executed during the period of depression, themes of ‘poverty and gloom’ are prevalent in his early paintings.

In Lowry’s The Removal (1928), a gathering of people stands in front of a residential building with items of furniture scattered around them. The artist chooses a title that suggests the subject of the painting without explicitly revealing its theme. Of course what is really displayed is an eviction, as residents of the building are forced out of their home onto the snowy winter pavement. In another painting, The Fever Van (1935), passersby on a main street peer down a side passage where a group of somber people look on as a hidden figure is loaded into an ambulance. The scene suggests not only the suffering of the fever inflicted victim, but also the community at large. The Removal and The Fever Van are unusual in their depiction of a narrative, whereas many of Lowry’s paintings bypass a story in preference of atmosphere.

The artist found beauty in the particular encounters and the feeling of tension that prevails in times of uncertainty. Lowry found this uneasy mood combined with the shadow of pollution permeating the landscape to be deeply fascinating.

Jessica Stephens writes in The Studio in January 1928:

“…The aim of this artist seems to be that of telling this stark England what it looks like, deliberately, sternly, without mitigation, but without, as one can testify, exaggeration. It is the nearest rendering of the life of Lancashire one knows.”

During the 1940s the artist turned his gaze to the devastation of war. In Blitzed Site (1942) a lone figure stares out at the viewer from amidst blackened debris as four men in the distance search for lost pieces of their lives amongst the wreckage. A bare white background suggests an ash covered landscape, standing in stark contrast to the dark foreground in this bleak depiction. One feels the familiar sense of hopelessness seen in Lowry’s earlier works, but more powerful is the sense of awe awarded to the crumbling remnants of the post-Blitz industrial scene. This is common in his wartime imagery, as figures are overwhelmed by the strength of their surroundings.

Following the Second World War Lowry’s representations of the working class became increasingly vibrant and cartoon-like. This did not prevent him, however, from selecting themes of illness and war related deformity. The Cripples (1949) is cluttered with grim yet humorous characters, themselves dominating the picture. A central figure stands on crutches facing the viewer, pale faced with a pained expression; an amputee rides in from the lower right hand corner on a wheeled board, propelling himself forward with the use of his hands. The scene is filled with these types. The deliberate ugliness and awkward malformation of these characters directs attention to the ordinary tragedy of the day.

In earlier years Lowry’s greatest patron had been the Manchester Guardian. The newspaper frequently reproduced his paintings and twice offered the artist a position as an art critic (which he refused on both occasions). Lowry’s true notoriety came later, once he had ceased painting the scenes for which he was most revered. Later works focus on empty landscapes or individual portraits, although he always maintained a predilection for sadness. The artist died in 1976 at 88 years old, shortly before the opening of a retrospective at the Royal Academy. The attendance of the exhibition was record breaking, boasting the most visitors to date for the work of a 20th-century artist.