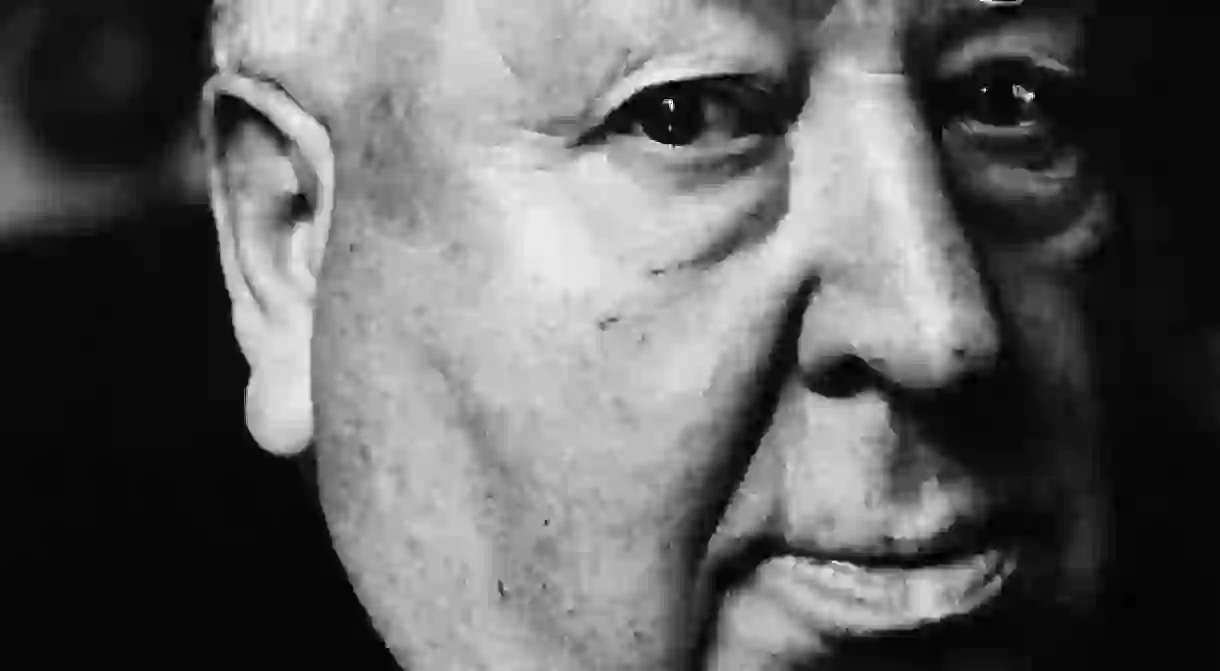

The Best Alfred Hitchcock Films

Born in 1899 in Leytonstone, England, Alfred Hitchcock is revered as one of the most significant film directors of all time. Passionate and committed to cinematic experimentation, Hitchcock directed over 50 films in his lifetime, and continued to work until his death in 1980, leaving his last project, The Short Night, unfinished. To celebrate the life and work of this iconic figure, we list ten of the best Hitchcock films.

Blackmail (1929)

An early work in Hitchcock’s career, Blackmail is not only significant in Hitchcock’s filmography, but also in the history of British cinema. Considered by many as the first British ‘Talkie’, the film was originally intended to be a silent movie, but was adapted to include sound during the filming. The story follows the psychological trauma of Alice White (Anny Ondra) after she murders a man with a knife while he attempts to rape her. Hitchcock’s brilliance is truly evident in this film with his experimental use of sound. An example of this is the renowned ‘knife at breakfast’ scene, where one character tells a story, repeatedly uttering the word ‘knife’. The camera then focuses on Alice’s face and the voice of woman’s story becomes inaudible muffled, except for the repetition of ‘knife’.

The 39 Steps (1935)

Another film that pre-dates Hitchcock’s move to Hollywood, The 39 Steps was an adaptation of John Buchan’s novel of the same title. Widely considered the best of his early films, The 39 Steps follows Richard Hannay as he tries to stop the spy organisation The 39 Steps, while also running away from the police as he is accused of murdering the agent he was actually trying to help. The film traverses the British landscape, as Hannay escapes from London to Scotland and back again, passing cultural landmarks like the Forth Bridge. The film is famous for introducing the ‘MacGuffin’ to Hitchcock’s cinematic vocabulary. This plot device takes the shape of an unexplained item/person that the characters care immensely about but the audience does not understand, and is used to drive the story while creating constant intrigue.

Rebecca (1940)

Rebecca was Hitchcock’s first move into Hollywood and its vast success can be seen as a pivotal point in his career. A psychological drama, the film focuses upon the haunting memories of a dead wife, Rebecca, and the destructive effects this has on the widower Maxim de Winter and his new wife, an unnamed protagonist. Based upon Daphne du Maurier’s novel of the same name, and starring Laurence Olivier, Joan Fontaine, George Sanders and Judith Anderson, this film won two academy awards and was the opening film at the 1st Berlin International Film Festival in 1951.

Rope (1948)

Hitchcock’s first film in colour, Rope is a cinematic landmark that once again proved Hitchcock’s love for experimenting with form. Seemingly taking place in one continuous shot, the film unfolds in real time. The film opens with the characters Brandon Shaw (John Dall) and Phillip Morgan (Farley Granger) murdering an old classmate, and then unfolds as they host a dinner party in the crime scene. With the aim of proving their intellectual superiority, the murderous duo invite the victim’s father to the dinner while the body sits in the room, hidden in a large chest. On release Rope divided critics, with many feeling that the drama was inferior to Hitchcock’s previous technical experimentation, however it is still celebrated as a fine example of the crime thriller genre. The American film critic Rodger Ebert wrote of the film, ‘Rope remains one of the most interesting experiments ever attempted by a major director working with big box-office names’.

Rear Window (1954)

Rear Window is a masterpiece of voyeurism, both in content and filming style. Portraying a claustrophobic setting, the film takes place inside the apartment of a photojournalist, who is incapacitated because of a broken leg. With his rear window being his only view of the outside world, Jeff watches the inhabitants of the surrounding apartments, when his voyeurism leads him to view what appears to be an attempted murder. James Stewart plays the protagonist brilliantly and Hitchcock’s direction is inspiring. A masterwork of suspense, this film has been loved unanimously by cinema fanatics for its comment on voyeurism and cinema, and for its dexterous use of music and visual techniques.

The Trouble with Harry (1955)

The Trouble with Harry represented a deviation from Hitchcock’s thriller reputation, and instead takes the form of a dark comedy. In the film, the ‘trouble with Harry’ is that he is dead, and the residents of the small village in Vermont are not sure what to do with his body. The story unfolds as the main characters continually bury, dig up, move and conceal the title character, hiding him from the police, while also figuring out which one of them actually killed him. While this film might catch suspense fanatics by surprise, The Trouble with Harry is a clear example that Hitchcock was a genius of multiple genres.

Vertigo (1958)

Continuously revisited by critics and fans alike, Vertigo is a thriller than blurs the lines of the supernatural and psychological. James Stewart plays the main character Scottie, a retired detective with a severe fear of heights and vertigo. Scottie reluctantly re-enters employment when he is hired to follow a friend’s wife who is thought to be possessed. The narrative develops into a detailed and suspenseful story peppered with twists, and is a fantastic example of Hitchcock’s prowess. The film has been featured on numerous lists as one of the greatest films of all time.

North by Northwest (1959)

Returning to the spy thriller genre, North by Northwest’s storyline resembles The 39 Steps, following an innocent man on the run and a secret organisation who aim to smuggle top secret government information. By this point in his career Hitchcock’s mastery of suspense and concealing story information was widely renowned, and the film delivers these aspects flawlessly. North by Northwest is recognised as a pivotal film in the spy genre, being a major influence on the James Bond movies, and even the opening titles can be seen to have inspired future filmmakers, with the movie opening with a vibrant music score by Bernard Herrmann and animated text that interact with the background.

Psycho (1960)

Containing one of the most iconic film scenes of all time, Psycho was a controversial film that pushed the boundaries of the horror genre and also the international production film codes of its time. Based on Robert Bloch’s novel, the film was produced on a tiny budget compared to North by Northwest, and was a testament to the possibility of making great movies with minimum funds. When Psycho was originally released in cinemas, Hitchcock insisted that the theatres enforce a ‘no late admission’ policy, ensuring that the film’s suspense was not disturbed by late cinemagoers. Unnerving both visually and audibly, Bernard Herrmann’s harrowing string compositions have become one of cinema’s most recognisable sounds.

The Birds (1963)

Another masterpiece of horror which has been recognised as his last great work, The Birds is a classic Hitchcockian thriller that has stood the test of time. Fusing the natural with the supernatural, the film presents the story of a town that is under siege by brutal bird attacks. A somewhat bizarre and unexplained narrative, the film has inspired many interpretations, some drawing on themes of horror theory, nature vs. mankind and feminism. The illusive storyline however is what has made this film so iconic, and stands as evidence that even at this late stage in his career Hitchcock put experimentation at the fore of his creations.