An Introduction to Francis Bacon in 9 Paintings

Irish-born painter Francis Bacon was one of 20th-century Britain’s most influential artists. His grotesque, ethereal depictions brilliantly reflect the timeless agony of being human; some works exploring the macabre theme of inevitable death, others celebrating love and friendship.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944)

One of Francis Bacon’s classic triptychs, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion examines, in detail, the secondary characters depicted at the foot of the cross in religious paintings. Bacon translates their apparent agony and devotion into three hybrid beasts akin to “The Eumenides, vengeful furies of Greek myth,” according to the Tate. The painting was first exhibited in 1945—the same year that photographs and films of Nazi concentration camps were released. “For some,” the museum’s analysis continues, “Bacon’s triptych reflected the pessimistic world ushered in by the Holocaust and the advent of nuclear weapons.”

Painting (1946)

Portraying what MoMA describes as an “oblique but damning image of an anonymous public figure,” Painting is a raw manifestation of Bacon’s reaction to the mortifying events of World War II. Hovering above the lower half of the central figure’s menacing face is a black umbrella, perhaps alluding to former British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, who was often photographed with an umbrella in hand. The figure dons a black suit formally adorned with a yellow rose, set to the brutal backdrop of a butchered cow carcass. The subject’s “deathly complexion and toothy grimace suggest a deep brutality beneath his proper exterior,” MoMA explains—a discomforting juxtaposition also supported by the cuts of meat speared just above a luxurious carpet running through a room resembling the inside of Hitler’s bunker.

Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953)

One of Bacon’s best-known paintings, Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X is one of almost 50 renderings the artist created of the 17th century figure. Diego Velázquez’s mid-17th century depiction of the pope served as Bacon’s foremost inspiration, despite never having seen the portrait in person. But while Velázquez’s portrayal is collected and authoritative, Bacon paints chaos in perpetual motion, trapping his subject in an eternal, primal scream. As noted by the Des Moines Art Center where the painting is located, Bacon’s representation of Pope Innocent X is a clear reference to the famous Battleship Potemkin scene, in which a woman silently screams after being shot through her glasses.

Figure with Meat (1954)

Another painting inspired by Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (c. 1650), Figure with Meat is a disturbing depiction of Pope Innocent X sat in front of a cow carcass cut lengthways in half. The carcass is a common motif that runs through Bacon’s work, the result of the artist’s long-time fascination with butcher shops and appreciation for Old Master portrayals of meat in still life. Bacon’s inclusion of the carcass is a direct reminder that in the end, death awaits each and every one of us.

Three Studies for a Crucifixion (1962)

After nearly 20 years, Bacon revisited the theme of his 1944 painting, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. But instead of ghostly beasts, this later triptych showcases three gruesome scenes of butchery. Bacon saw the Crucifixion as a paradigm of both personal and collective human suffering, which the late artist felt was best represented through butchered animals—symbols of slain innocence, perhaps, or maybe examples of inevitable demise. Bacon believed that animals could sense their impending doom, an existentialist concept that he related to and revisited throughout his career. “We are meat,” he said. “We are potential carcasses.”

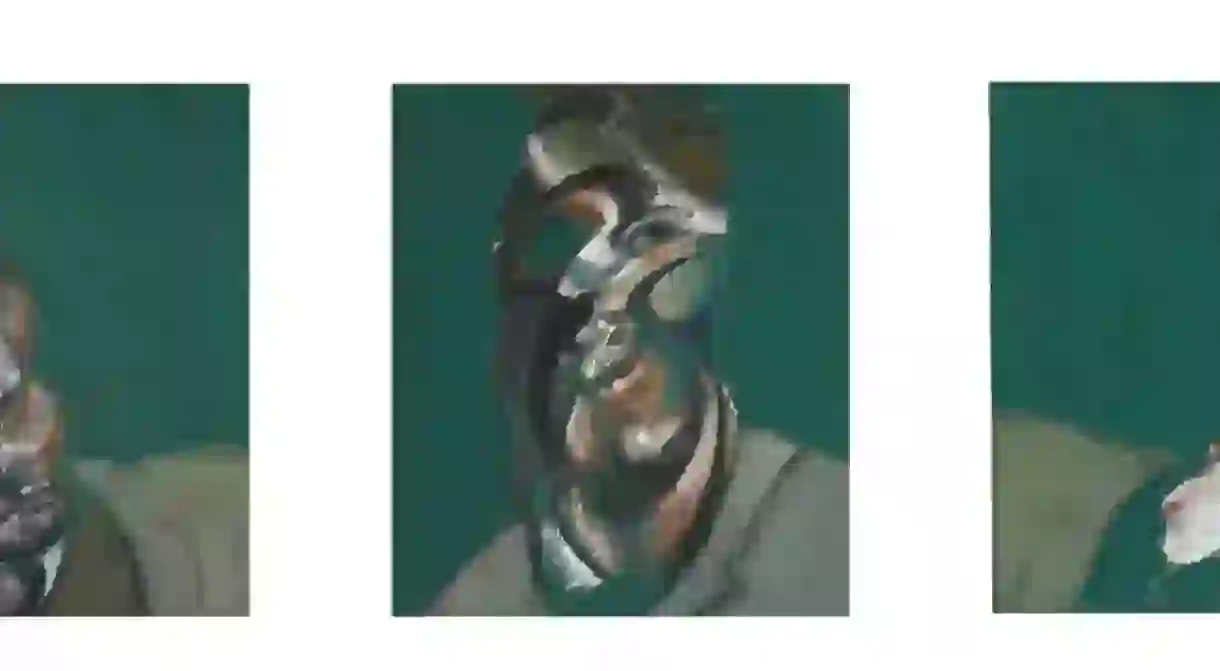

Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer (1963)

Francis Bacon met George Dyer early in 1963. By that time, Bacon was one of Britain’s most respected artists, and he recalled the story of their first encounter as one of excitement; namely, that he caught Dyer breaking into his studio. Dyer, nearly 15 years Bacon’s junior, would become the virtuosic painter’s lover and muse. Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer was painted early on in their relationship “when Bacon’s passion for the younger man was at its most fervent,” Christie’s explains. “It was completed during the period of greatest personal and professional contentment in Bacon’s career.”

Three Studies for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964)

Sold for over £23,000,000 at Sotheby’s London, Three Studies for Portrait of Lucian Freud was painted at the height of Bacon’s career. But what makes this triptych particularly significant is the subject. Alongside Bacon, Lucian Freud was one of Britain’s most revered painters. The two were also inseparable friends, which lends a softness to Bacon’s rendering. “Among these phenomenal character investigations, the brilliant colour, dramatic brushstrokes and analysis of facial landscape across the three canvases of the present work are truly exceptional,” Sotheby’s said of the masterpiece.

Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969)

Bacon’s later triptych depicting Lucian Freud is unusual for its color palette. While the artist typically utilized deep, rich shades of burgundy, orange, and black, Three Studies of Lucian Freud is rather light and airy. Unlike Three Studies for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964, above), Bacon’s 1969 triptych portrays his friend (and artistic rival) from afar. Encased within a clean prism, Freud appears animated, changing positions across each frame. Three Studies of Lucian Freud was painted at a time when the relationship between Bacon and Freud was at its strongest. In the following years, their friendship would deteriorate due to professional tensions. Three Studies of Lucian Freud was sold at Christie’s New York for a record-breaking $142,405,000 in 2013.

Three Studies for a Self-Portrait(1979-80)

Bacon’s three-part self portrait, housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was a study in the artist’s features as well as his psyche. The depth of the black backdrop skews the viewer’s perspective of space, though each angle of the artist’s face—despite its blurs and obscurities—provides a fluid sense of ethereal motion. “I loathe my own face,” Bacon said in 1975. “I’ve done a lot of self-portraits, really because people have been dying around me like flies and I’ve nobody else left to paint but myself.”