A Tour of Tokyo’s Traditional Kissatens

Kissatens are far from regular cafés. These Japanese coffee shops are inspired by traditional teahouses, built during a time when the West had a strong influence on culture and aesthetics. Culture Trip takes a tour through Japan’s local history, via some of Tokyo’s most iconic kissatens.

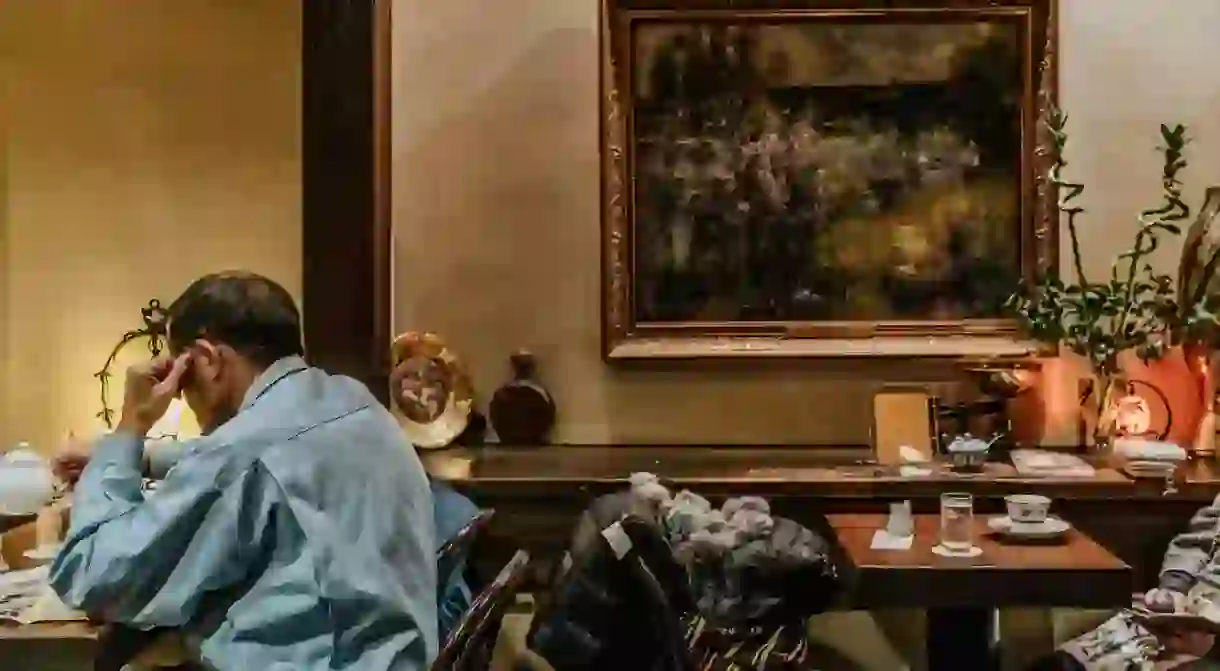

The cavernous kissaten is a dark, comforting space – an embodiment of your pipe-smoking grandfather’s favourite cardigan. The air is thick with the aroma of roasted coffee beans and a trail of smoke lingers from the end of a burnt-out cigarette. The space inspires a sense of nostalgia for a time when jazz music was all the rage and terms like “decaf” and “frappuccino” were decades away from existence.

Where’s the espresso machine? Is a “café au lait” just a latte? Are laptops allowed? You can ask these questions, but chances are you won’t want to risk breaking the silence. The only other sounds you’ll hear are rustling newspapers and mumbles of intimate chatter between customers.

The history of Japan’s kissaten culture

Kissatens are a distinctly Japanese phenomenon, born from what is known as the “third place”. This isn’t your home (first place) nor your workplace (second place), but somewhere in between: somewhere where you can simply be. For a country where dwellings are notoriously small and compact, spacious kissatens were once a necessity. They were community living rooms of sorts, frequented by people living, working and passing through the area.

Kissatens are a product of the nation’s Shōwa-era (1926–1989): a period that directly preceded the economic boom of the late 1980s. They were born at a time when the nation was rapidly becoming more international, thanks to its role as a major player in global economics. The hardworking salaryman was an aspirational figure and money was more abundant than ever.

During this time, Western influence was on the rise through popular media, allowing these coffee houses to truly come into their own. Many took inspiration from American diners and European cafés, adding their own dose of Japanese traditionalism.

Weary salarymen would snooze in Tokyo’s kissatens between marathon meetings, while students pulled long study nights fuelled by cups of bitter black brew. In 1949, following the end of an import suspension and a rising interest in Western culture, coffee started flowing more freely.

The kissaten became a different place for different people. For some, it was a taste of international culture. For others it was a music outlet, a peaceful space in which to listen to jazz music at a time when personal record players were rare. It was also the perfect breakfast and dinner location for a new age of salarymen, who were making the long commute from regional areas to the city.

Nowadays, the rise of coffee chains such as Starbucks and Tully’s Coffee have swept through Japan’s cities, where entrepreneurs hold power pitches and trendy teens stage selfie shoots. Yet there is still a faint, trailing kissaten presence throughout Tokyo. Here are some of the spaces that maintain these traditions of the past.

Homegrown hospitality

Nestled 300 meters northwest of the billboard-covered Shibuya Crossing is Chatei Hatou, one of Tokyo’s best-known kissatens. Though the interior design may have you guessing otherwise, this is one of the younger coffee establishments of its kind. It opened in 1989 – over a decade after the height of kissaten craze.

Push open the heavy door to Chatei Hatou and you’ll find a dark wooden counter lined with chairs. Here you’ll get a front-row seat to the meticulous coffee-making process, which involves hand-poured drip brewing techniques. Deep into the space is a large communal table, which is a good spot for a leisurely afternoon.

Classical jazz soundtracks the café, and helps create a calm and soothing environment designed to inspire clients to slow down and retreat from everyday life for a moment or two.

“At the beginning, people warned us against opening a shop like ours,” reflects Iwanami-san, Chatei Hatou’s owner on the venue’s launch.

Iwanami-san remembers naysayers who said a space like Chatei Hatou “was not a match for these times”. And to be honest, they weren’t necessarily wrong. By 1989, Japan was already in the midst of a modern coffee shop evolution, with chain stores like Doutor Coffee popping up across the city. This switched out the ideologies of community and loyalty for one of accessibility and convenience.

Against the imposing odds, Iwanami-san and his loyal league of coffee masters persisted, hoping to be there for “those people who wanted take a break”. Over the years, this raison d’être has contributed to Chatei Hatou’s surprising success. When the energy of Tokyo living gets too much, locals flock to this inner-city sanctuary. Some even make it a daily meditative ritual.

Incorporating old coffee-making style and slow methods, some orders at Chatei Hatou come with a 20-minute wait time. There’s no cookie-cutter training manual here – the only thing that matters is, according to Iwanami-san, “the coffee must be delicious.”

The brewers are also responsible for selecting a cup that best suits the aura of the customer. Perhaps it could be a blue-trimmed saucer to match the blue of your jacket collar or a polka-dot cup to go with your umbrella. It’s these little touches that keep people coming back, and this level of attention to detail that makes this kissaten much more than a café.

Tokyo’s Elvis Presley generation

Music plays a significant role in the culture of many of Tokyo’s kissatens, but nobody takes it quite to the same level as Café Sky. The venue is located in Sugamo, a neighbourhood affectionately known as “Grandma’s Harajuku” thanks to its large population of advanced-aged residents. Café Sky is a shrine to all things Elvis – the American poster boy of the Sugamo generation.

The interior of this cosy café is covered in Elvis paraphernalia. Life-size posters, ticket stubs, faded photographs and tourist-shop souvenirs of the “king of rock ’n’ roll” decorate Café Sky from floor to ceiling. The place is an excellent example of how a kissaten can become an extension of the people who run it.

“I just love Elvis so much,” says Hiranuma-san, the café’s owner. “So it made sense to me to open a kissaten dedicated to him.”

The basement-level establishment opened around 40 years ago according to Hiranuma-san, which was around the time of Elvis’s passing. Given the timing of its opening, the café’s namesake is almost serendipitous. “I called the place ‘Sky’ after my favourite Elvis song, ‘I Believe In The Man In The Sky,’” he explains.

You’d think it might be difficult these days to source new Elvis memorabilia for the café, but Hiranuma-san has his connections. “I know someone in America, a friend who often sends me Elvis items,” he says. “About twice a year I’ll receive a package from him full of new souvenirs.”

In recent years, the old-world charm of Japan’s ageing coffeehouses have become a site of pilgrimage for international guests, and Sky is no exception. “Lately we’ve had quite a few foreign visitors, which is great; I love it,” says Hiranuma-san. “I really just wish I could speak English so I could communicate with them better.”

It doesn’t matter though, because you don’t need to speak Japanese to understand the warmth and hospitality of this veteran coffee shop owner and his staff.

Asked whether he thinks it’s vital for kissatens like Café Sky to remain open, Hiranuma-san says he doesn’t have the perfect answer. There is one thing he is confident of, however: “I just want to keep it running as long as I’m alive.”

With this thought, he ruminates on the cafe’s name. “Because the place is tucked deep in the basement, there’s something important about naming the café ‘Sky’,” he says. “I don’t know what it is exactly, but I like the idea that although we’re deep underground, we’re always looking up.”

Keeping kissaten culture alive

It’s easy to get sentimental about these dingy, smoky coffee houses – places which have chosen to eschew current trends in favour of preserving the charm of the past. But chat with the owners of these establishments, and they’re far more pragmatic. When asked at 4pm on a Wednesday afternoon whether she’d be able to answer some questions for an interview, Iwamoto-san, the owner of Kissabonna, a café near Tokyo University), replies curtly, but politely enough, “No, I’m too busy.”

In an age of social media, online clout and self-promotion, a response like this might seem almost unfathomable. But unlike the minimalistic third-wave cafés that dot the trendy inner-city neighbourhoods, these places are perhaps apprehensive about trying to be more than they are. The kissaten is a space to relax, unwind, and detach from the outside world, at least for a little while.

Now is the time to visit your local kissaten. With the rise in endless coffee options expanding and diluting the market, they may not be here forever.