Liu Yi-Chang, Literary Pioneer Of Hong Kong

“Rusty feelings visit again on rainy days; thoughts are playing hide-and-seek among the smoke puffs” – given how frequently this opening sentence of Liu Yi-Chang’s The Drunkard is quoted, one does not have to be a littérateur to find it familiar. Liu Yi-Chang, with The Drunkard (1963) and Tête-bêche (1975) being his most well-known masterpieces, is definitely a leading novelist in Hong Kong.

Liu Yi-Chang’s Early Years

Born to an intellectual family in Shanghai, Liu Yi-Chang (Liu) demonstrated his acute observation instinct and writing talents via his first novella Anna Fuluoski in Exile (1935) at the early age of 17, basing on white Russian women resorted to be prostitutes for survival. As a philosophy and politics major, Liu chose to be an editor immediately after his graduation from St. John’s University. He continued writing as supplement editor for the anti-war newspapers, including National Gazette during World War II period. Meanwhile, in 1946, he established Shanghai Huai Zheng Wen Hua She for the publishing of quality literary works.

Because of Chinese Civil War and the death of his father, Liu came to Hong Kong alone in 1948 wishing to explore a larger market for publication. Yet soon he was running out of money, and therefore took up a number of editorial positions – at his peak he wrote for 13 newspapers and periodicals per day. His life as a writer had not been as romantic as one’s projection, which is the background and source of inspiration of his ground-breaking novel, The Drunkard.

The Drunkard

Poetic and free-flowing at the same time, The Drunkard is said to be the first Chinese novel displaying the stylistic traits of stream of consciousness writing, presenting readers with the protagonist Old Lau’s uninterrupted interior monologue and psychological landscape. Yet from Liu’s perspective, the novel should neither be confined to nor categorized as merely demonstrating a particular literary technique, for his creation was purely driven by the pursuit of innovation.

“You do not have to follow another’s path; you carve your own one… You have to be different. An outstanding novel is simply about ideas” – this is how Liu responded to all the praises of The Drunkard for its techniques employed.

Literary style aside, The Drunkard did portray a vivid and socially connotative picture of the contemporary Hong Kong society. The protagonist, Old Lau, is a passionate and talented middle-aged writer whose vision of a genuinely flourishing local literature scene gets engulfed by reality, eventually turning himself into an erotic novel writer. Setting the impotence of intellectuals against the prevailing social climate unveils the struggle of a writer in his age. In an interview, Liu recalled how rare Sing Tao Weekly was to have accepted his avant-garde works, while the majority of its counterparts asked for writings centering on bar girls. Such frustration should be echoed by every striving intellectual of his times, as he writes in the preface of The Drunkard — “an intellectual would be self-torturing and twisted when he endeavored to survive in a gloomy age.”

Tête-bêche

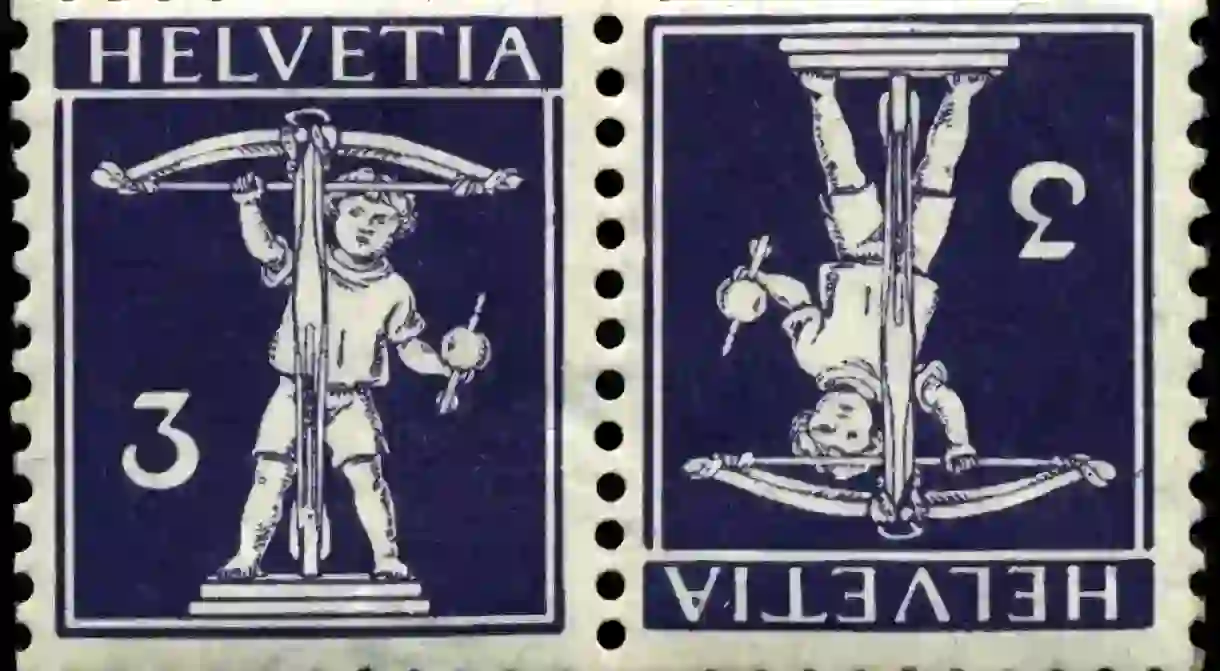

The charisma of Liu’s writing goes beyond the literature scene, proving how far a boundary-pushing idea could go. Among his own collection of postage stamps, Liu was particularly attracted by those of the tête-bêche design – a pair of stamps upside-down relative to each other. Such intriguing relativity and altered symmetry was a major thread in Tête-bêche (1975), in which the once and for all encounter of two protagonists was their side-by-side presence in the cinema.

The beauty of ambiguity and intersection in mere fantasy is delicately visualized in In the Mood for Love (2000), one of the most acclaimed works by the renowned auteur Wong Kar-Wai who fell in love with and drew inspirations from both The Drunkard and Tête-bêche. Tribute was paid to Liu Yi-Chang via the movie’s mise-en-scène, in which lines from Tête-bêche are directly quoted and presented on the big screen. His atmospheric cinematography, together with the novel’s theme of subtlety, demonstrates the borderless nature of literary aesthetics.

Every reader would have his or her own imagination of ‘life as a writer like Liu Yi-Chang’, that under the portrayal of Wong Kar-Wai would be a nostalgic and melancholic one. Yet in reality, Liu is never an idealist or a realist — there is just a clear line in his mind marking the essential difference between livelihood and interests. Once he has remarked, “during daytime I write to cater for the crowd; at night I write what I love exclusively for personal pleasure and satisfaction.” As simple as that, Liu’s honesty might explain the boldness in his pioneering literary works.