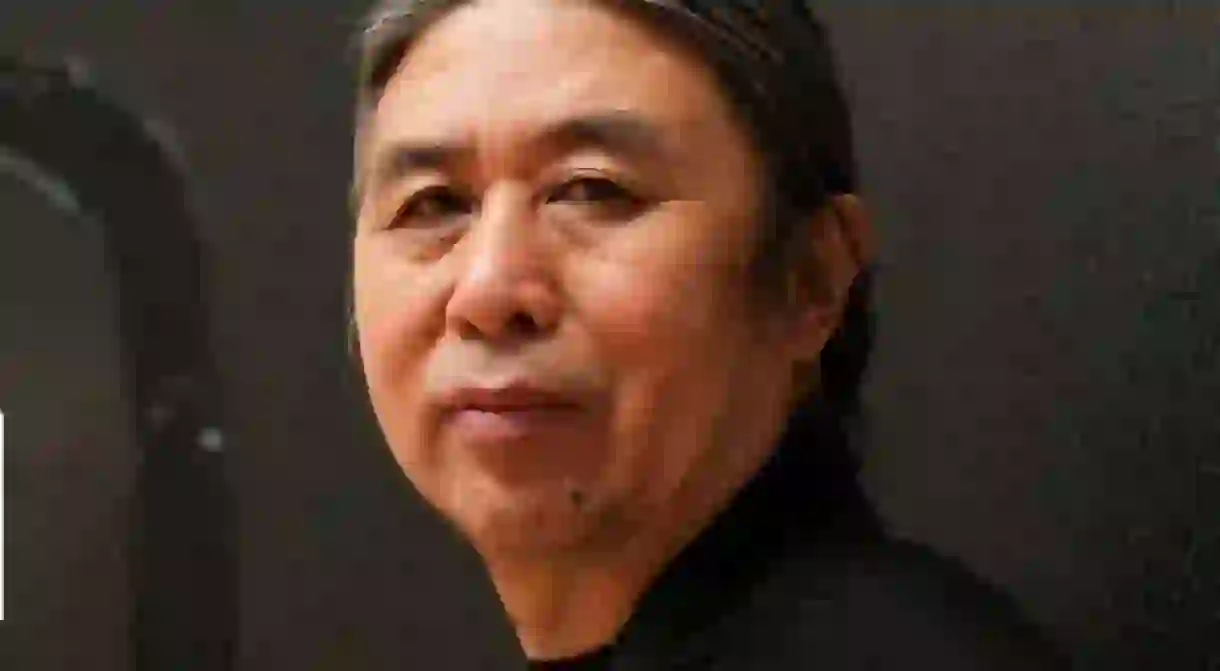

Interview with Chinese Artist Tian Wei: Calligraphy in the West

Contemporary artist Tian Wei spent much of his life traveling between the United States and China, which left a profound mark on his painting style and ideas. Although his work is heavily influenced by the works of Western and particularly Russian masters, it also demonstrates a strong attachment to the art of Chinese calligraphy, and conveys a complex combination of Western and Chinese aesthetics. Culture Trip interviews the artist about his fascinating background and signature style.

Before you moved to America to pursue your education at the University of Hawaii, how deep was your knowledge of Western art?

I had very little first-hand knowledge of Western art in the 1970s and 1980s, certainly not of contemporary and modern art. You have to remember the political structure in China at that time. We called Western art ‘realistic style’ and while we, the Chinese, knew much about our own system, there was not the information available about Western art in printed form to study or view, so all I could read and view were badly printed visuals or black and white photocopied material of famous works. It strikes me that now we have almost too much information readily available, but then it would have been very unusual to see a good reproduction print of a work by a French Impressionist in China.

However, it was possible to have an understanding of European art through a Russian art context. You could study European art under some of the top Russian art professionals of the time, so I am very familiar with Russia’s style of painting, its dramatic and sometimes melancholic works. Russian art is very good and it still has the power to move me. We had an understanding of 19th century European art history, so I knew of the work by the Impressionists, but I did not view any works created by these artists in a gallery until later on in my life.

Your art has been described as the merging of American abstract expressionism with the tradition of Chinese calligraphy. Can you talk a bit about the significance of this integration of styles and how you arrived at your signature technique?

Well, actually, I disagree with the notion that I am merging American abstract expression with the tradition of Chinese calligraphy. I disagree, because it is against my initial approach. My work is drawn from a Chinese perspective and one which is based on Chinese calligraphy. A major difference between the East and West is how it perceives calligraphy, because in China it is revered as an art form, and it is not recognised as such in the West. Chinese calligraphy has an ideographic meaning and, over the centuries, each picture has become more abstract. I was heavily influenced by this and by Chinese history. What I am attempting to do is to innovate and create the Chinese Way of Abstraction. When I moved to America, I became aware of the work of the 1960s American abstract expressionists; however, the energy of the work is very different and comes from an opposite point of view. Regarding technique, at first – like most artists – I tried to understand and improve my skills, so I copied everything. I went to Honolulu Academy, the only art museum in the city. The museum staff were very encouraging and made me feel welcome, even allowing me to set up an easel in the museum. I spent copious amounts of time copying the Western masters and Realism, and eventually recognised the power of the abstract. By the mid-1990s, I was creating large-scale works with an ‘oriental flavour’. However, the knowledge portrayed comes from my training in Chinese calligraphy; for example, how I use my brush is informed by Chinese calligraphy, while my palette is influenced by Russian colours.

How important has your experience in the United States been to the development of your artistic approach?

It has been very important. Uli Sigg (collector) once said to me a ‘Chinese artist cannot do what you do and an American artist cannot do it either. You can, because of your experience’. It was in the United States that I began my second education of over twenty years, and I think education does not begin or end exclusively with the academic world; it continues with your life experience.

In the United States, I started to learn about a Western lifestyle; its political system, its contradictions, the freedom you are supposed to have, what you love and what you learn to dislike. I also learned to appreciate the difference, for example, the air of London is cleaner than in Beijing. In my situation, you can’t help but compare two very different systems. I learnt to be honest, to be true to myself. I didn’t follow a certain fashion because I wanted the opportunity to express my life experience.

Your paintings can be distinguished from Western abstraction through their inclusion of writing, and thus meaning. To what extent is language itself significant to your work?

Language is extremely powerful. It can be used to transmit, to communicate clearly and when not, the message and meaning can be misconstrued. Language affects every aspect of my life, from work, art, career, to my family – from speech to the written form, language affects it all. Regarding my work, you have to understand that I am constantly searching for the meaning of words and reflecting on their beauty, exposing their power and finally reflecting upon the invisible.

How important are both Western and Eastern artistic tradition to your paintings? In other words, do you see any inherent conflict in your use of language in an abstract painting, or likewise painting English text in the style of Chinese calligraphy?

Both traditions are important and my work reflects my experience of life in both worlds. However, I think I already commented that my practise is drawn from a Chinese perspective and that I work with Chinese calligraphy as my primary source. In the West, you have painting and sculpture as art forms, in the East, calligraphy is considered a third art form. In the U.S.A, you use a pen for writing; in China (at least when I studied at school), you use a brush. There are thousands of characters in Chinese and twenty six letters in an English alphabet. Chinese calligraphy has evolved over centuries from a recognisable system created of pictorial characters, into the abstract characters the Chinese use today. My work is not ‘abstract’ in a Western sense, as the bottom line is that you can read and recognise the English words on the canvas. Indeed, this is what I meant when I stated earlier that I create contemporary Chinese abstraction. The words can be read by an English language speaker but a Chinese-only language speaker will become puzzled; the use of a brush to paint English words conveys an energy that would be understood by the Chinese, as they would understand the hidden power of the pressure of the brush-strokes, its speed, its rhythm and the philosophy. But it is also possible that they would not be able to ‘read’ the words. Man has always been inspired by nature, and Chinese calligraphy refers to it and to life itself. What I attempt to do, when I paint a word, is to try to catch a moment – one you might dream of – for instance the emotion you feel before a first kiss with the love of your life – a life experienced through energy captured. I am very interested in creating a ‘conflict’ by working with two contrasting language systems.

One can’t help but look at your art as largely autobiographical. Do you identify yourself more as a Western or Eastern artist? Or do these two parts of your identity sit in equal balance?

In the USA, I never entered the mainstream and being from China, it was hard to do so, simply by being Chinese two decades ago. I am also aware that I ‘blocked’ myself, because of the various barriers others and I created. When I lived in the USA, the difference between me and my adopted country’s culture became apparent; however, now that I am living and working once more in China, I am also experiencing the same thing. So, I have to start again to conquer this difference of perception and it can be tricky, but it also doesn’t matter – you see, I’m not an American or a Chinese artist. It is just not that simple, I am not one or the other because my experience of both worlds exists at the same time – it’s like the two sides of a coin. What fascinates me most is that there can always be a switching – perhaps even a continuity – between both sides.

Since moving to Beijing in 2011, how has your art been received back in your home country?

It’s difficult to say, and maybe this needs time for people to fully understand. I still know that the message can get ‘lost’ in translation from Chinese to English and vice versa. I work between both worlds and you have to learn to handle both. It’s an interesting case of language becoming a barrier to communication, rather than a tool of correspondence. However, this can bring mystery and through mutual taste, relationships can evolve. The hidden power of the work is there, it is exposed and ready for a response; you just have to figure it out.

Tian Wei’s exhibition continues until 5th April at October Gallery London