Intervision, the Communist Counterpart to Eurovision That Didn’t Quite Work

Can’t get enough of the annual glitter-fest that is Eurovision? Go back in time and behind the Iron Curtain to discover the rise and fall of the Intervision Song Contest, a Communist rival to Eurovision and unexpected frontier of the Cold War.

When you think of the Cold War era, missiles and astronauts may well be the images that come to mind. But this period of geopolitical tension also had a more flamboyant, altogether sparklier face in the form of the Eurovision-esque Intervision Song Contest. Born of the Sopot Festival, which was initiated by Władysław Szpilman of The Pianist fame in 1961, the rebranded Intervision hit TV screens in 1977.

The Eastern bloc’s answer to Eurovision

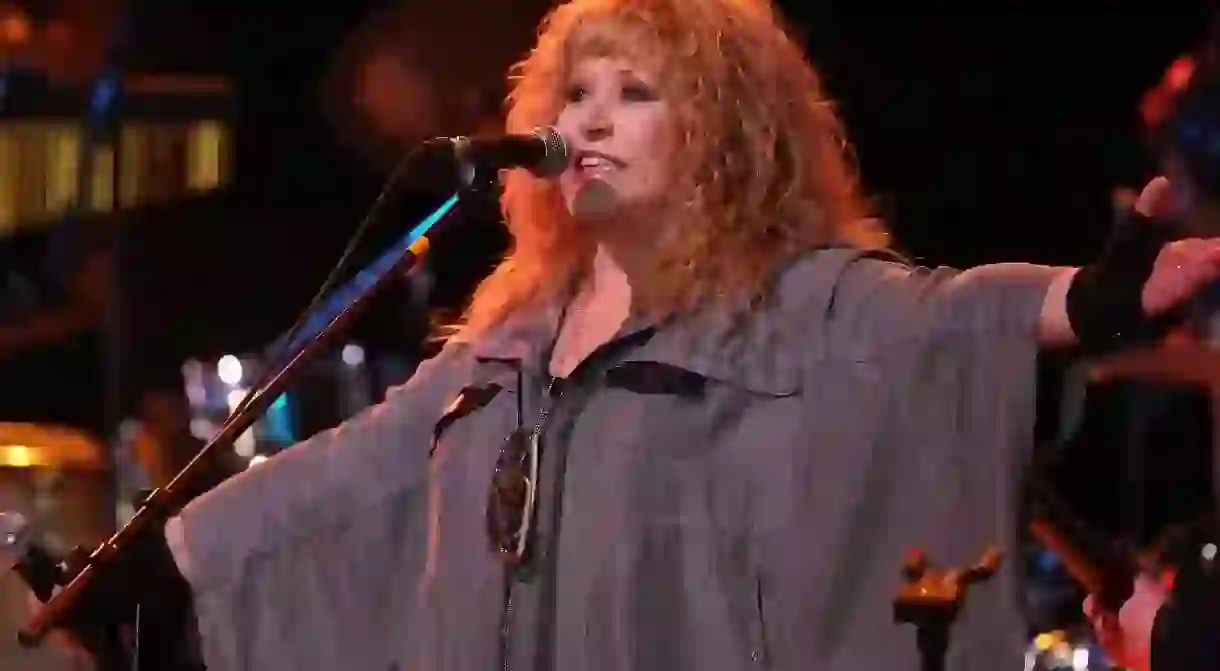

This short-lived spectacle of musical one-upmanship, directed pointedly westwards as an embodiment of the phrase “anything you can do, we can do better” but also inwards as a tool of solidarity, saw Eastern Europe’s best and brightest take to the stage to win the hearts (and ears) of their regional compatriots. Such big names as Alla Pugacheva – known as the Queen of Russian pop – and legendary Hungarian pop-rock star Kati Kovács attempted to bring home the Intervision glory for their respective nations.

Intervision largely mirrored the Eurovision formula, with a couple of notable exceptions. First, Intervision allowed viewers at home to vote from the get-go, while Eurovision still relied on juries. The only slight catch was that not many of these viewers had phones. Simple solution: In order to vote for a song, the audience would instead simply turn on their lights, with the surge in power consumption used to calculate the number of votes. The jury’s out on exactly how accurate this method was, but the contest’s organisers should certainly get points for innovation. Second, the winning country was not lumbered with the responsibility and/or privilege of hosting the following year’s competition, which always took place in the Polish seaside town of Sopot.

The politics of song contests

From stage invaders to lyrics with a not-so-subtle subtext – we remember, for example, Georgia’s earnest 2009 attempt to enter a song titled ‘We Don’t Wanna Put In’, a swipe at the Russian president – Eurovision has taught us that song contests can be veritable theatres of musical war. Despite official intentions to promote ideas of solidarity among Socialist states in tune with Communist ideology, Intervision too found itself a magnet for controversy.

We might imagine Moscow to be the mastermind of such an event and the contest’s centre of gravity, but herein lay a key bone of contention. While the Soviet Union wielded the most political and military might in the region, its power was not necessarily replicated in this area of the cultural realm. It was the more “Western” contestants, seen as more prosperous, modern and stylish, who tended to top the leaderboard. Soviet entrants, meanwhile, often got a negative reception. Polish host Jacek Bromski was also known for his veiled barbs against the USSR. This is not to say, however, that Soviet contestants were a model of Socialist pride and refused to engage in subversion; it was Russian Queen of the airwaves Alla Pugacheva who caused one of the contest’s biggest stirs, when she made the sign of the cross at the end of her performance, undermining the doctrine of state atheism.

Today, Eurovision casts its net far and wide, welcoming singers from Lisbon to Baku and even Australia, but in the 1970s Intervision was seemingly the more open of the contests, with a host of non-Eastern European countries taking part. Canada and Cuba were two distinctly distant nations that competed, while Finland’s Marion Rung even took the trophy home in 1980 for her performance of ‘Where Is the Love’; Rung had already won Eurovision in 1973. It was the interval acts, though, that gave Intervision the edge in terms of an all-embracing cast list: to name just two, American soul legend Gloria Gaynor and iconic British singer Petula Clark were among the international stars to perform at Intervision. The censorship of Boney M’s performance of hit song ‘Rasputin’ in 1979 – which the disco-pop band sang despite requests from the Polish broadcaster not to do so – shows, however, that these diverse interval acts were not a straightforward celebration of global music. With media tightly controlled throughout the Eastern bloc and clamouring fans unable to tune in to potentially subversive content from overseas, the invitation extended to some of the world’s biggest stars served in part as a tool to placate audiences, offering them a state-sanctioned taste of the West.

Speaking to Culture Trip, Eurovision academic Dr Paul Jordan explains that he sees Intervision as a useful gauge of the political landscape. “I have argued that Eurovision reflected the political map of Europe and so too does Intervision in a way,” he says. “Finland, which is on the periphery of Western Europe, participated in both, and achieved more success with Intervision […] Conversely, Estonia never participated in Intervision, which is reflective of the political direction in the country. (Estonia was always more Western-focused during Soviet times.) Intervision itself was never popular in Estonia, but Eurovision was – they used to watch it illegally on Finnish TV.”

The death and failed revival of Intervision

Despite an outwardly winning formula, Intervision saw its fourth and final year in 1980. The song contest was one of the first institutions to fall in the wake of the unrest in Poland embodied in Solidarity, the opposition movement often dubbed the first step towards the collapse of the Soviet Union. With Poland proving politically unreliable, broadcasting the show – mere miles from the birthplace of Solidarity – was deemed too risky.

Fast-forward to 2014, when Russia proposed an Intervision revival in a fit of anger against the “moral decay of the West”, particularly in response to the Eurovision victory of drag queen Conchita Wurst. With the majority of former Intervision contestants firmly in Eurovision’s orbit – illustrated by the failure of another short-lived Intervision resurrection in 2008 – President Putin’s new iteration of Intervision would look farther east. The sparse line-up was to encompass the member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) in a deft feat of cultural diplomacy that would see Russia partner with superpower China and grow its cultural links in opposition to the West.

Alas, the contest was persistently postponed and never materialised. The impulse that drove the rise and soon-thereafter fall of Intervision in both its iterations nonetheless carries a useful lesson: Culture and politics don’t always dance to the same tune.