The Stories Behind Marrakech’s City Gates

Each of the gates in Marrakech’s ochre-red city wall has a story to tell, be it an ancient battle, a failed rebellion, or a medieval customs post to stop any alcohol sneaking into the city. Here are the hidden stories behind the city gates of the medina.

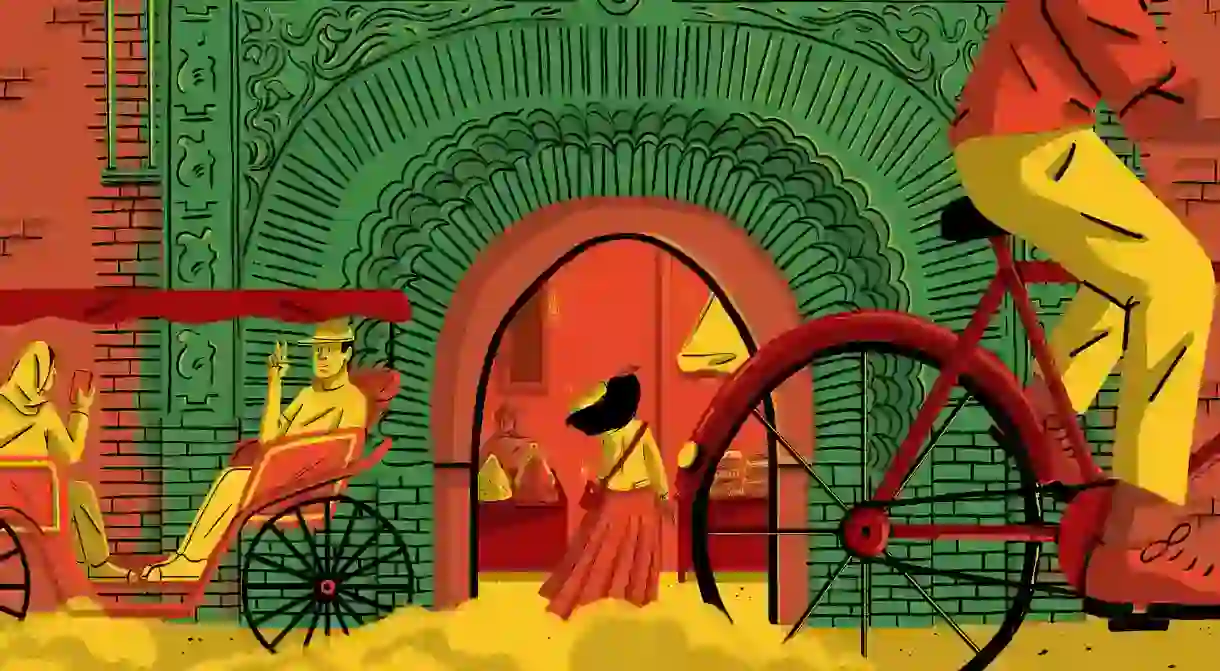

The walls around Marrakech’s Medina (old city) are punctuated by a series of gates, some old, some new, but each with its own story. The best way to take them all in is by doing a circuit round them in a caléche (horse-drawn carriage), although you can do the same tour, if you prefer, by bike or even on foot (twelve miles, so bring water). Because the walls have been expanded to the north over the years, one of the original city gates is now well inside the Medina. Others have been remodelled various times. When the walls were first built in 1126, there were twelve gates; now there are nineteen, plus a few small, unofficial ones. Let’s check them out.

The walls

When the Almoravid Dynasty swept up out of the desert in the eleventh century to conquer Morocco and found Marrakech, they built a circuit of walls around their city to defend it. Made with red earth from the surrounding plain, the walls were (and still are) ochre in colour, and so Marrakech became known as the Red City. Today, even outside the walls, in the modern Ville Nouvelle, buildings are still faced in that same hue. It looks particularly beautiful on the ramparts along the west side of the Medina when lit up by the setting sun.

Bab Agnaou

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

The city’s most impressive gate is Bab Agnaou. It leads to the Kasbah, a walled-off area within the already walled Medina. But actually, the gate is older than the Kasbah, and was originally just the main southern entrance into the city. Unlike the walls and the other gates, Bab Agnaou isn’t red, but grey, made from a locally quarried slate-like stone, carved with decorative scallops and floral designs. It is surrounded by Koranic quotations written in a beautiful Arabic script called kufic. The name means “Black people’s gate”, possibly because it was used by black slaves of African descent, or perhaps because it leads south, across the Sahara to West Africa.

Bar er Robb

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

Outside Bab Aganou, on the road leading south, is Bab er Robb, which means “fruit syrup gate” – although you won’t find much fruit syrup there today. The name comes from the time of the Almohads, who ousted the city’s Almoravid founders in the 12th century and were very keen to clamp down on any whiff of booze. As a result, all grape products, including grape syrup (robb) had to pass through this gate to be checked by customs. Today’s gate only dates back to the 19th century, but its previous history harbours one rather gruesome episode: in 1308, after crushing a rebellion against his rule, sultan Abou Thabit apparently displayed the severed heads of some 600 insurgents on top of it, although it is not entirely clear how he managed to fit them all on.

Bab Aylen

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

Like Bab Debbagh, Bab Aylen was one of the city’s original Almoravid entrances. The gate you see here today may not look very exciting, but historically it was the scene of a battle that took place in 1129, just three years after it was built. The Almohad invaders, besieging the city with the aim of wresting it from the Almoravids, tried to storm the gate, but were stopped by its defenders, who came from a Berber tribe called the Banu Aylen. The gate took its name in their honour.

Bab Aghmat

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

After another 18 years of siege, it was through Bab Aghmat that the Almohads finally broke into the city. This time, the gate was defended not by Berber tribesmen but by a demoralized bunch of Christian mercenaries. When the Almohad sultan Abd al-Moumen promised them their lives, they capitulated and the gate fell. The Almohads then entered the city and set about razing just about everything which their Almoravid predecessors had built. Almost the only thing that remained – apart from the Almoravid koubba on Place Ben Youssef – was the city’s wall with its twelve Almoravid gates, this one included. Unfortunately, the gateway that you see here today is not the original one which capitulated to the Almohads back in 1147. Like almost all of the Almoravid city, that has long gone.

Bab Taghzout

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

Bab Taghzout is a bit of an oddity. It’s one of the city’s twelve original Almoravid gates, but it isn’t even in the city wall. Today, Bab Taghzout is in the middle of the Medina, with not a rampart in sight. So how does this venerable old gate end up so far from the city’s outer wall? The answer lies in the area to its north, centred around the mausoleum of the twelfth-century Sufi saint Sidi Bel Abbes. In the 17th century, establishing a pilgrimage route around the city’s most important holy men’s tombs, sultan Moulay Ismail included Sidi Bel Abbes in the circuit. By the 18th century, the area around his tomb had developed into a full-blown residential neighbourhood, and sultan Mohammed III decided to extend the city wall northward to encompass it. As a result, Bab Taghzout was left marooned inside the Medina, where it remains to this day.

Bab Debbagh

Architectural Landmark, Historical Landmark

Bab Debbagh is the tanners’ gate. No prizes for guessing why if you go there: the stink alone should tell you that just inside the gate are the city’s smelly tanneries, where leather is cured by an age-old process in vats of tannin and pigeon poo. The river, running directly outside the gate, is the reason why the tanneries are located here, as they need water and drainage. The gate itself is one of the city’s oldest, and though it must have been remodelled several times over the centuries, it still has a chicaned passageway through it to slow down any invading forces who might be trying to get into the city. There is a stairway up to the top, where you’d get a view over the tanneries, but unfortunately it’s usually closed.

Bab el Khemis

Historical Landmark, Architectural Landmark

The city’s northernmost gate is called Bab el Khemis, which means “Thursday Gate”. The reason is the huge flea market just outside it, which nowadays takes place every day except Friday, but was originally a weekly market held every Thursday, and Thursday is still its biggest day. The gate itself, refurbished in 1803, dates back to Almoravid times, and actually, with its frilly, round entrance, and topped with battlement-like protrusions called merlons, it can’t be that different from how it looked back in the eleventh century.